This guest post by Rhianna Shaheen appears as part of our theme week on Demon and Spirit Possession.

(MAJOR SPOILERS AHEAD!)

I have a Twin Peaks problem. I love Twin Peaks (1990-1991). In college, I was so obsessed with the show that I animated a Saul Bass-inspired titles sequence and wrote a spec script for my screenwriting class. However, as I became a better feminist, I awoke from my stupor of admiration for the show. I began to question the dead girl trope and ask myself, what is so funny about the sexual abuse and torture of an adolescent girl? I’ll admit I was thrilled about its announced return in 2016, but I wonder if a continued story will do more harm than good. Will the show continue to pull the demonic possession card when it comes to violence against women?

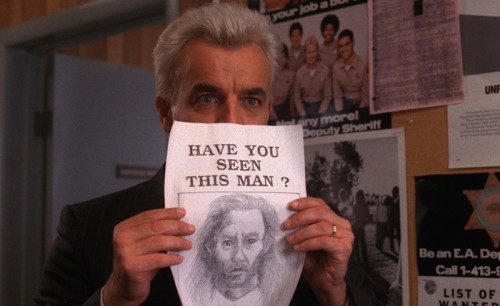

In the TV series, Special Agent Dale Cooper first encounters the evil spirit BOB in a dream. However, no one seems to see BOB in real life except for Sarah Palmer, who becomes increasingly unstable and otherworldly after her daughter’s murder. Much of this is due to her terrifying visions of BOB as well as her husband’s recent, strange antics. When Maddy Ferguson, Laura’s lookalike cousin, comes to support the Palmer family she sees similar visions of BOB in the house.

In the hunt for Laura Palmer’s killer, the local Sheriff’s Department is absolutely useless. As soon as Agent Cooper turns them on to Tibetan method and Dream Logic, all serious detective work goes out the door. It also doesn’t help that the town chooses to project this crisis outside of “decent” society. According to Sheriff Truman:

“There’s a sort of evil out there. Something very, very strange in these old woods. Call it what you want. A darkness, a presence. It takes many forms but…it’s been out there for as long as anyone can remember and we’ve always been here to fight it.”

But this old evil is within the town as well as outside of it. The show’s “quirky allure” tricks viewers into believing that Twin Peaks is different. That some places remain untouched by patriarchal evil. When we discover that it was Leland Palmer we are shocked. Leland’s mirrored reflection of BOB exposes the threat as one within the confines of the domestic space. It is patriarchy passing itself off as the loving and benign father of the nuclear family.

But what is even more shocking is that an entire community allows this to happen. In the prequel film, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me (1992) we follow Laura Palmer through the final seven days of her life. Unlike the series, Laura has a voice here. We get to see her walking, talking, and acting like a teenager. When pages from her secret diary go missing she confides in her friend Harold that “[BOB] has been having [her] since [she] was 12” and “wants to be [her], or he’ll kill [her].” Harold does not believe her. It’s an extremely painful scene, because not only do we know she will die, but we know that many real-life victims of childhood abuse are often not believed either.

Days before her death, Laura finally discovers that it is her father. At dinner, Leland torments his daughter’s dirty hands and questions her about her “lovers.” Leland then pinches his daughter’s cheek. The sheer look of horror on Laura’s face is heartbreaking as she looks into the eyes of her abuser. Her mother, Sarah All-I-Can-Do-Is-Scream Palmer, tells her husband to stop, saying, “She doesn’t like that.” He replies, “How do you know what she likes?” It’s absolutely chilling, but even then the mother remains ignorant. How can everyone be so clueless?

As viewers, the warning signs seem obvious. The only way Laura can cope with this parasitic spirit is through copious amounts of cocaine and promiscuous sex with strange, older men. Why would a Homecoming queen who volunteered with Meals on Wheels, and tutored disabled Johnny, act this way? Well, to anyone schooled in recognizing sexual abuse the answer seems obvious. As many as two-thirds of all drug addicts reported that they experienced some sort of childhood abuse. The link between prostitution and incest or sexual abuse has also long been established.

Now this brings us to the question: Who’s at fault for Laura Palmer’s murder? Was it poor Leland or the demon that possessed him?

Moments before his death, Leland confesses his guilt to Agent Cooper:

“Oh God! Laura! I killed her. Oh my God, I killed my daughter. I didn’t know. Forgive me. Oh God. I was just a boy. I saw him in my dream. He said he wanted to play. He opened me and I invited him and he came inside me.”

With fire sprinkler water pouring over him, Leland seems cleansed of his sins. Lynch paints a pretty sympathetic portrait of Leland. He is cursed and tormented rather than murderous and abusive. He is blameless for his actions. Leland gets to go “into the light” while Laura is condemned to the purgatory of the Black Lodge.

In Diane Hume George’s essay Lynching Women: A Feminist Reading of Twin Peaks she perfectly discusses the problem with Leland’s poignant ending:

“We are instructed regarding how to situate our sympathies and experience our sense of justice. But this is just another clever use of the simplistic formula by which lascivious misogyny is presented in loving detail, […] scapegoating offenders whose punishment casts off the guilt that belongs to an entire culture ethos. And that ethos, both pornographic and thanatopic, not only goes free. It gets validated.”

Things become even more fucked up after Leland’s funeral where people remember him as a victim. Agent Cooper gives Mrs. Palmer some words of comfort:

“Sarah. I think it might help to teII you what happened just before LeIand died. It’s hard to realize here [points to her head] and here [points to her heart] what has transpired. Your husband went so far as to drug you to keep his actions secret. But before he died, LeIand confronted the horror of what he had done to Laura and agonized over the pain he had caused you. LeIand died at peace.”

I’m sorry, but death does not absolve you. Horrible people die and somehow we’re supposed to forget the history of horrible things they have done? We all die. This does not erase our actions, even if you’re a white cis male.

For a minute, let’s forget that BOB is a thing (ESPECIALLY when you consider that most of the town has no knowledge of these spirits and how their worlds work). These people are celebrating the memory of Leland Palmer after (I assume) finding out that he murdered and raped his own daughter (along with Maddy Ferguson and Teresa Banks). Excuse me, is anyone else bothered by how much denial these people are in?

Like many fans, I turned a blind eye, preferring to seek refuge in the myth of Killer BOB and the Black Lodge rather than identify the clear signs of abuse in front of me. As Cooper says: “Harry, is it easier to believe a man would rape and murder his own daughter? Any more comforting?”

While I no longer indulge the BOB theory, I do read BOB as patriarchal oppression. Its truth is one that women (Laura, Maddy, Sarah) see and know too well. Cooper only solves the mystery when he FINALLY believes and listens to a woman. Laura Palmer must whisper in his ear, “My father killed me” for him to finally understand.

M.C. Blakeman writes:

“While he may ultimately let Leland off the hook by claiming he was “possessed” by the paranormal “Bob” the show’s resident evil force, the fact remains that the women of Twin Peaks and of the United States are in more danger from their fathers, husbands and lovers than from maniacal strangers.”

I do believe that Lynch and Frost meant to use BOB as “the evil that men do” and as a means to understand family violence and abuse, but they jump around the issue so much that it only reflects uncertainty. The show’s inability to hold evil men responsible for their actions is too reminiscent of our own society. As soon as we answer “Who Killed Laura Palmer?” the show does its best to rebury the ugly truth that we so struggled to uncover. After that it fully commits to understanding the mythos behind it. This is troubling to me. As one of the most influential shows on television, Twin Peaks created a narrative formula that will forever shape the way this country looks at rape and child abuse. It’s important that as viewers we constantly question this, even if it is disguised as harmless, intellectual programming.

Rhianna Shaheen is a recent graduate from Bryn Mawr College with a BA in Fine Arts and Minor in Film Studies and Art History. Check her out on twitter!

Well said. I agree completely and have never been quite able to articulate my discomfort surrounding the deflection of blame. Thank you for writing this!

I’ve just started watching Twin Peaks. And, as a TV addict, I’ve gotten used to the “dead girl trope”. But then it starts: Laura has been abused all her life. So, it’s not that she’s a woman who likes sex, she’s acting out. The “real” Laura is the good girl and she’s forced to be “bad” because of the violence she has endured.

And then, Bob. The non-guilt of Leland. I was enjoying the insanity of dreams and otherworldly things, but this went too far. Violence is done by people. I have just watched the two episodes that have that “reveal”. Now, I’m pissed off and bored with this show at the same. I’m going to finish it because I’ve come this far. But the enthusiasm is gone. It’s patriarchal and bad story-telling.

It seems to me that the nuts who took over Twin Peaks after Lynch more or less abandoned the show during season two were responsible for the “Leland is not guilty because of BOB” idea. In fact, Lynch in *Fire Walk With Me* (as you point out) puts the responsibility back on Leland himself (though not 100%), and I hope the new show (if it tackles these issues at all) does the same.

But, yes, so problematic that Leland is forgiven in Episode 16, that the town comes together to mourn a man who sexually abused his daughter all her life, that the local authorities wouldn’t look to the parents first, etc.

Interestingly, when I was a religious teenager watching this show when it was originally on, I bought the BOB thing all the way. When I watch it now as a nonbeliever, I try to watch BOB and company as metaphors. (It doesn’t quite work, but it makes for better viewing.)

This article was difficult for this guy to make sense of, as it was written in Feminist, typically twisting things around to match-up with the feminist discursive template. In “making sense” of Twin Peaks this way, you miss the whole point of it.

If it’s any consolation to you, however, my own mother had been possessed by a demon that caused her to abuse the sh*t out of me for the first 17 years of my life, including trying to suffocate me with a pillow when I was two years old (my earliest memory). At age 22, living on my own, the demon which had possessed my mother visited me while I was undergoing withdrawal from narcotics (which weakened my spiritual defenses), and I literally wrestled it as it pressed down on my chest, trying to keep me from breathing. I put up a fight for hours, until the demon left at dawn. That’s probably something you’ve never heard about in Women’s Studies courses, but can’t say that it’s the strangest thing that’s ever happened to me. And no, I do not hate women, I just cannot love them – thanks to the demon that had possessed my mother.

What an absolute crock of shit, as you Americans would say. Try reading Leland’s dying words again…”I was just a boy. I saw him in my dreams. He said he wanted to play. He opened me and I invited him and he came inside me.” Now start understanding and appreciating what that statement might really mean…from a sexual abuse POV. It is clear that Leland was also sexually abused/raped (possessed), hence the double-meaning that can be implied from his statement.

The abused (child) Leland, went on to become the abuser of his own

daughter, but under the aegis of a dark form of (real) possession…in

the form of Bob. You might not put any or no faith in the area of the

supernatural, but Lynch does and always has…it is a huge part of the

shows mythos, absolutely massive. Cooper’s understanding of this

‘possession’ element, is what leads him to allow Leland to have a

dignified death. The scene is presented in such a way, that it is clear

that Leland was subject to a form of spirit habitation.

The entity that is Bob, first makes ‘etheric’ contact via the victim’s dreams…this happened with Cooper too (even before he entered the town of Twin Peaks) and it ultimately leads to him being inhabited (see climax of TV show). The 3rd season would’ve had a Bob-possessed FBI agent running around Twin Peaks…a far more useful entity to Black Lodge, than a schoolgirl. Bob ultimately wanted to possess Laura (not Leland) and he nearly achieved his aim (see train car scene from film), but was thwarted by the superior hierarchy of the Black Lodge, who he is subordinate to.

Laura’s ultimate fate (as shown in the film) is one of the most positive and uplifting things in the entire film/series (her redemption, after death in the Red Room, her soul was saved, unlike Windom Earle, who was damned), a film/series that is clearly set in a dark and mysterious setting. Laura ‘wanted’ to die…do you not understand that? Laura wanted to die…she wanted to be free (that is what the last 7 days is about, ffs!) and she makes it.

The reason that Laura’s ‘soul is saved’ is because it was a ‘soul’ that was worth saving. You cite all the good things she did, regardless of the horrific abuse…’meals on wheels’, ‘helping Johnny Horne’ etc. She was a decent human being and that is the tragedy of the whole story…she cannot ultimately be blamed for actions, as a child (whilst under the aegis of possession and/or familial abuse).

You don’t indulge the BOB theory…because you simply don’t have the capacity to understand it…that is not surprising, as Lynch is one of the most impenetrable film artists in the business.

Even if you don’t want to accept the supernatural-possession angle as being tangible…it would almost be a prerequisite to have to ‘couch the abuse’ in the garb of the supernatural…if only to be able to get away with dealing with such an important and sensitive subject and on ‘prime time’ TV.

Put it like this…

“Hi CBS, I want to make a prime-time TV show about a father who sexually abuses his own daughter.”

“Really, that sounds fascinating, the public will love that idea, it literally sells itself and the advertisers will fall over themselves getting slots among all that familial carnage. Hey, I know they usually like to watch Moonlightning, Beverley Hills 90210 and Law and Order (and other mental candyfloss) but they’ll eat this abuse angle up…oh yeah.”

No other TV show or most films for that matter…would ever have even touched on this most important area of abuse (not at that time in history, circa 1990), a national syndicated TV show, whereby collective America is being shown that the abuse of minors, can and is often within the family home. This is just another example of why Twin Peaks was a landmark/watershed moment in TV. This was brave and ambitious material to be tackling back then and you’ve done the series/film a huge disservice, with your slanted agenda.

I can remember that time back then…and no show is even comparable in this regard.

I don’t wish to be this harsh, but when I see folk totally misunderstanding the dynamics and complexities of the series/film…it makes my blood boil. To then take this misunderstanding (and/or lack of belief) and next fashion it into some kind of feminist rant, is imo, an embarrassing thing to witness.

Quote from article “as I became a better feminist, I awoke from my stupor of admiration for the show.”

This basically reads like the following:

“As I lost my grasp on the complexities and dynamics of the show, I found that resorting to (entrained) feminist theory, was an easier way to explain away, what I didn’t and couldn’t understand. This made me feel better about myself and all my shortcomings, could then be dispensed with and I could still maintain a pretense of understanding.” (that is what the real underlying message is, within that statement).

If this is the level of understanding that film-schools, Universities are throwing out there…they probably need closing down.

If you (sorry, I mean author of the article) had any idea about Lynch as a film-maker, TV (writer, producer, director) and artist…you wouldn’t have put pen to paper (fingers to the keyboard) in this way. Mulholland Drive is in a similar vein to Twin Peaks and I did a massive piece on it a few years ago, relating to these very same types of themes. Feel free to peruse, just so you know where I’m coming from.

No…I don’t have any training (brainwashing) from film-schools or media study units…which (ironically) must’ve helped me massively.

This is what it takes…to at least have an appreciable understanding of Lynch and his work…I warn you, it is not a few paragraphs, that have been skewed to fit a feminist agenda.

http://subliminalsynchrosphere.blogspot.com/2012/12/new-post.html

Excellent piece. This is really the crux of the issue: is Bob an apt metaphor for incest and the denial surrounding it, or an escape hatch lending Leland a way out of his own culpability? I’ve written, discussed and made videos about Twin Peaks over the past few years and this question has always been at the inescapable core of that work, even when the focus was on other matters. I tend to feel that the film redeems the series’ missteps, just barely, by articulating Laura’s abuse in such visceral terms and creating a lot of textual evidence that Leland knows exactly what he is doing and bears the responsibility. On the the other hand, the episodes you describe are the absolute low point of the series’ attempts to understand abuse, and in fact represents the opposite tendency: a desire to sweep trauma under the rug and run desperately in the other direction.

Twin Peaks is less a consistent artwork than a hodgepodge of influences which (to my mind) mostly coalesces in the end despite itself, and thanks to Lynch’s last-minute course correction in the finale and film. As such, it’s worth observing that Lynch neither wrote or directed these episodes and reportedly had little to do with them, and wasn’t on set when they were shot (indeed, after directing the reveal episode he didn’t come back to direct anything until the finale, despite a few guest appearances as Gordon Cole). This speaks well to his aesthetic and dramatic interests but poorly of his ability or willingness to exercise control over the narrative he helped start. In some ways I think Fire Walk With Me is his attempt to atone for that act. It’s interesting that the media tore him apart so viciously for that attempt: they were fine with Twin Peaks when it treated sexual violence as a mystery tease, but lost all patience when it dared to go deeper and do something so rare in televised crime fiction – give voice to the victim.

Like you, I’m both excited and nervous about Twin Peaks’ return. I have no doubt Lynch will return to the core subject of the series as he did in the film, but will he serve to obscure Leland’s responsibility or to highlight it? He is a filmmaker who loves to tell the truth, and also loves to mystify and keep secrets and I don’t feel the latter impulse is the nobler one when it comes to this subject matter (his oft-repeated desire to have not revealed the killer is, I think, a terrible one). Even when I first saw FWWM, I was not comfortable with its incorporation of the supernatural (particularly with the possession angle) into such a psychologically real story, and while I’ve mostly come around on that I’m not beyond fearing that the creators could lose the thread once again. I suspect they won’t, but we’ll have to wait and see.

Btw, if you & your readers are interested – or even paying attention at this late date – here is the video series I made about Twin Peaks, which articulates my views about the overall shape and meaning: http://thedancingimage.blogspot.com/2015/02/journey-through-twin-peaks.html

I know this is an older post, but just read this and wanted to reply. I agree 100% that below the kooky surface of the original series lies the truth that Laura Palmer was the victim of incest and abuse at the hands of her father. There are a few uncomfortable scenes in the beginning of the series which hint at Leland’s sexual feelings towards his daughter (when he throws himself on her coffin and the broken mechanism starts going up and down, when he’s dancing with her photograph in the living room). This also helps explain Laura’s secret rebellious side and drug use and, as you said, many prostitutes have a history of sexual abuse.

The presence of BOB does complicate matters in the series. I think in Season 2 when Cooper explains how Leland was possessed by BOB and people have a hard time believing this supernatural explanation he says something along the lines of “is it easier to believe a father would rape and murder his daughter?” which, come on now, are we that naive? Leland mentions letting BOB in when he was a boy. This confession that he voluntarily let BOB in means he can’t be completely absolved of his sins/crimes (although he says he was just a boy, and seems like he didn’t know what he was doing). As one of the earlier commenters mentioned, we can also take this as implying Leland was sexually abused as a child and thus he was continuing the pattern of abuse.

If Leland is mostly let off the hook in the series because he was “possessed,” I think the picture is different in Fire Walk With Me. There’s the scene where Laura runs from the house after seeing BOB in her bedroom and then, hiding around the corner, she sees her father leaving the house and says something like “Please don’t let it be him.” Despite all the metaphysical elements at play in Twin Peaks its very possible to view BOB here as a mental projection Laura created to block out the fact that it is her father who has been raping her since she was 12. Laura’s self-destructive streak and the fact that she keeps pushing the people that love her away, because they don’t know her or won’t understand her, again all makes sense if we think of her as a victim of incest. She feels guilty, she doesn’t think people will believe her….

Maybe it’s possible to accept that Leland raped and murdered his daughter and at the same time believe there is an abstract, malevolent evil out there. People like Leland are responsible for their own actions, but there is evil out there (and “in the heart’s of men”) which we cannot understand.