|

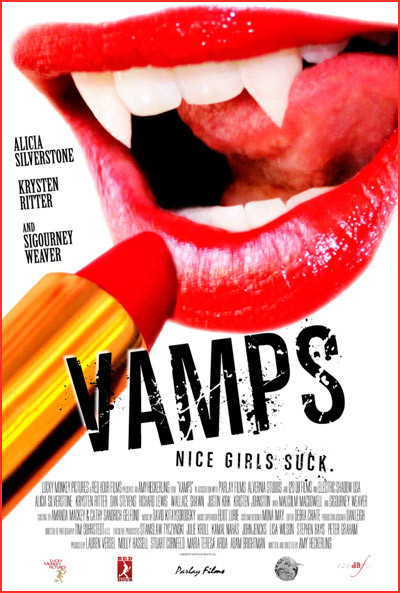

| Movie poster for Vamps |

Jason Buchanan on Rotten Tomatoes effectively captures the plot as follows: “Radiant New York City vampires Goody (Alicia Silverstone) and Stacy (Krysten Ritter) find their immortality in question after learning that love can still smolder in the realm of the undead. Meanwhile, Russian bloodsucker Vadim (Justin Kirk) prowls the streets in search of the next big thrill, and Dr. Van Helsing (Wallace Shawn) seeks to exterminate the creatures of the night as young Joey Van Helsing develops an unusual fixation on Stacy. As ravenous ‘stem’ vampire Ciccerus (Sigourney Weaver) presides over her dark dynasty with the help of her loyal assistant Ivan (Todd Barry), oddball Renfield (Zak Orth) strives to impress Stacy and Goody by any means necessary. Amidst all of the bloodshed and intrigue, nefarious vampire Vlad (Malcolm McDowell) works to perfect his knitting skills.”

|

| Alicia Silverstone as Goody and Krysten Ritter as Stacy in Vamps |

[SPOILER] Case in point: one of my absolute favorite scenes in the film happens early on, when Goody and Stacy head out for their nighttime ritual of club-hopping and imitating the new dance moves of the local youth “Day Walkers” (the term they use to refer to The Living among them). A couple of particularly horrible dude vampires approaches a woman after she bends over, ass in the air, with the word “Juicy” written on her tight pants. The dude vamps merely introduce themselves to her, to which she responds, “I’ll get my coat.” Goody chastises the horrible dude vampires—Goody and Stacy drink only the blood of rodents, not humans—and the dudes respond with, “She’s asking for it,” referring to her “Juicy” attire. It’s a pretty fucking great commentary on the victim-blaming that always accompanies any instance of the rape or sexual assault of women.

|

| Stacy and Goody on the computer |

This scene makes me so happy for a couple of reasons. First, a woman intervening to help another woman avoid getting killed by two horrible dude vampires—an obvious metaphor for rape in this scene, rarely happens in movies. How lovely to see that! Because women looking out for their friends certainly happens in real life—first-hand experience! Second, while I don’t necessarily like the implication that women always go for Bad Boys, I appreciate the acknowledgment that bros like this, who want to harm, abuse, and assault women, definitely exist.

|

| Stacy, Goody, and Sigourney Weaver as Cisserus in Vamps |

Two words: Sigourney Weaver. Do we not adore her? The Alien films, mainly due to Weaver’s badass role as Ellen Ripley, remain one of the quintessential go-to franchises for getting that much-needed feminist fix that Hollywood movies today seem less willing to provide. (Quick shout out to Hunger Games, though!) And Weaver’s role in Vamps as Cisserus, the head vampire, or “Stem,” as they refer to the few vampires who possess the power to turn people into vampires, displays some feminist qualities—strength, leadership, and ambition, to name a few—but her character isn’t without flaws.

While the other vamps fear Weaver’s character—because she’s In Charge—they mainly fear her because she’s the evil, murderous villain. She obsesses over acquiring the love of young men, and when she doesn’t get it, well, you know, she eats them. In many ways, she reminds me of a vampiric version of Miranda Priestly, Meryl Streep’s character in The Devil Wears Prada. She often summons Goody and Stacy (by psychically speaking to them), and it’s almost always to make them model clothing. (Ha!) See, vampires can’t see themselves in mirrors (invisible!), so Weaver wants to look at these women wearing her very youthful, fashionable clothing so that she can visualize what it possibly looks like on her. Eventually though, Cisserus’ power goes so far to her head that she begins putting the other vampires in danger, and the tagline for the last act of the film basically becomes “This Bitch Needs to Die.”

|

| Vampires hanging out at the club |

Collider: What made you decide to jump into the vampire genre with Vamps?

Weaver: Well, I’m a big Amy Heckerling fan, and I also loved the character. She was so unrepentant … I love playing delicious, evil parts like that.

Collider: How does your character fit into the story?

Weaver: She is the person who turned the girls into vampires. So, they have to do her bidding, and she’s very unreasonable and demanding. I would have to say that the one change I made was that I thought she was not really enjoying herself very much, in the original script. I thought, “What’s not to enjoy?” She’s 2,000 years old, she can have anything, she can have anyone, she can do what she wants, so I wanted her to be totally in-the-moment. So, I talked to Amy about it and she just evolved that way. She’s a really happy vampire. She digs it.

|

| Stacy and Goody at the club |

That’s why this close relationship between Goody and Stacy is so important to see on The Big Screen in 2012.

In an interview conducted with the director Amy Heckerling by Women and Hollywood, Melissa Silverstein asks the question, “Do you have any comment on the fact that only 5% of movies are directed by women?” Heckerling’s response? “It’s a disgusting industry. I don’t know what else to say. Especially now. I can’t stomach most of the movies about women. I just saw a movie last night—I don’t want to say the name—but again with the fucking wedding, and the only time women say anything is about men.”

Word.