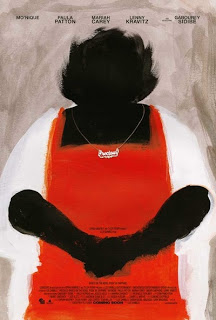

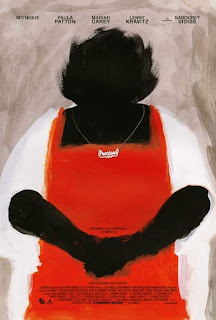

Last week, I saw the much-anticipated film Precious: Based on the Novel ‘Push’ by Sapphire. And I haven’t stopped thinking about it all week. Not because I’m in shock, though the film does depict a number of truly horrific and violent situations. And not because I’m blinded by completely uncritical love, because the film is far from perfect, and I recognize that. The reason Precious has stuck with me is because it is, by all accounts, an extremely well-made film. The acting is tremendous and the visuals feel authentic. And, best of all, the film is filled with strong, nuanced, and interesting female characters. In a time when women are often relegated to forgettable romantic comedies and bit parts in “male-centric” films, and when plus-sized women and women of color barely star in mainstream films at all, Precious is a welcomed break from typical multiplex fare.

I want to start by addressing the criticisms of Precious, because many of them are valid. The material is bleak — at times, perhaps, too bleak. Considering the lack of decent portrayals of people of color in film today, do we really need another film that highlights all the most negative things that might happen to a young woman of color?

From Racialicious:

So when I found out Push was being adapted for the silver screen, I cringed at the prospect of revisiting Precious’s bleakly rendered world. I dreaded watching in technicolor all the awful things I’d imagined while reading. And I reeeally didn’t want to return to the hollowness that haunted the ending. What possible reason would Hollywood have for further dramatizing an existence as heinous as Precious’s?It was certainly something to think about. Black American dramas have the tendency to pull their viewers into dark corners and assault them. The grittiest ripped-from-the-headlines realities and the woes so commonplace the news doesn’t bother covering them at all bogart their way into our fiction. Push will be no exception and I wasn’t sure if I should be pleased about that.

And, at the same time, the response to the film, though overwhelmingly positive, has tended to be superficial. As Latoya writes:

While Precious puts forth an array of issues, these are not engaged with by the reviewers. Is it because of the heaviness of the subject matter? Perhaps. But I find it interesting that I have seen more discussion of Mariah Carey appearing without make-up than any discussion of the underlying issues in the film.

Finally, there is the significant issue of colorism. Though Precious Jones has dark skin, the women of color who help her have light skin. While this is problematic all on its own, it’s even more of an issue when one considers that this casting doesn’t actually reflect the character descriptions in the book Push. Feministing has more:

In the book, the description of Blue Rain, the half-messiah, half-educator that delivers Precious from the bondage of illiteracy and abuse is as follows: “She dark, got nice face, big eyes, and…long dreadlocky hair.” (39-40) This character in the movie is played by Paula Patton, a light-skinned African American woman with straightened hair. By no means do I doubt the talent of Patton, but it means something that the directors chose to cast one of the most central characters of the film against Sapphire’s original description.

None of these issues can be ignored in discussing this film. And, sadly, these are the problems that will prevent Precious from being a great film, rather than just a very good film. In particular, I wonder why the decision to cast Paula Patton and Mariah Carey was made. While both women deliver fantastic performances, it’s hard to believe that there weren’t any actresses of equal talent who fit more closely to Sapphire’s descriptions. Though I haven’t read Push, it is my understanding that Blu Rain (the character played by Patton) is meant to be the positive embodiment of everything Precious dislikes in herself and her mother. The casting of a light-skinned woman makes this point much less clear, and it’s disappointing that Lee Daniels and the others involved in the casting of Precious didn’t do more to be true to Sapphire’s intents.

All that being said — Precious is still a very, very good film. Both Gabourey Sidibe and Mo’Nique deliver career-defining performances; this was Sidibe’s first film, and I hope we’ll be seeing much more of her in the coming years. And all of the female characters, including Precious, her mother, Blu Rain, Mrs. Weiss (a social worker, played by Carey), and the other girls in Precious’ GED class, are well developed and complicated. For instance, though Precious’ mother is characterized as a villain, I don’t think she can be seen in such polarizing terms. Though she commits horrible acts of violence and abuse against Precious throughout the film, we learn that there’s more to her than meets the eye and that her actions (as horrifying as they may be) are motivated by her own fears and insecurities. She may be a villain, to some degree, but she isn’t evil — much like Precious, she’s a victim of her own circumstances, and she is forced to make difficult choices. A similar character in another film may be depicted as completely one-dimensional, but Mo’Nique’s performance shows us that there is more to this woman — and to all of the women in the film, for that matter — than what initially appears on the surface.

Another strength is the way in which Precious handles its subject matter. Certainly, all of the issues addressed in the film — including (but not limited to) rape, incest, teen pregnancy, poverty and illiteracy — have been addressed before by other films, and when addressing such topics, it’s all too easy to come off sounding preachy or melodramatic. Precious does not fall in to this trap. Precious addresses these topics honestly and directly, never undermining the horror of it all but still making it clear that these are real aspects of life, and that they aren’t death sentences. Though the character Precious is forced to deal with a huge number of issues that no young woman should ever need to face, the audience is not supposed to pity her. Precious is too strong a character for that. Though the film ends on an ambiguous note, I left the theatre confident that she would go on and do well in life, because I had just spent the past two hours watching her face incredible odds and constantly surviving them with grace. We don’t want to see Precious experience all of the terrible situations she encounters, but we never fear or doubt her. She is clear-headed and determined, and she is a fantastic role model for all young women, from all walks of life. And we ultimately feel empathy, not pity, for her.

If you haven’t had an opportunity to see Precious, I highly recommend checking it out. It’s a flawed film, and it’s not something that will appeal to everyone. But for all its faults, Precious remains a strong film that addresses a wide variety of issues that need to be discussed candidly in film more often. And, if nothing else, it’s bound to be one of the most feminist movies you see this year.

Border Radio: 1987

Border Radio: 1987