|

| Panmela Castro |

Written by Amanda Rodriguez

“I was able to survive through the art of graffiti.” – Panmela Castro

Heloisa Passo’s short documentary Panmela Castro about the eponymous Brazilian graffiti artist and women’s rights activist is included as part of the Focus Forward: Food for Thought installment of the Tribeca Online Film Festival. In around three minutes, Castro manages to be inspiring and recontextualize graffiti art. Castro views grafitti as an act of expression that seizes women’s rights. She sees her art as a way to bring women together through the hosting of graffiti workshops for women where they make art while talking about women’s issues like domestic violence, the cycle of violence, and gender equality. In Castro’s vision, the movement of female-centric graffiti spreads from country to country as women share it among their communities.

I was also struck by what a male dominant artform graffiti traditionally is and how moving it is to see a group of women gathered around a building creating graffiti in a style that I’ve rarely seen, as it is a unique expression of the experience of being female in an oppressive patriarchal world.

|

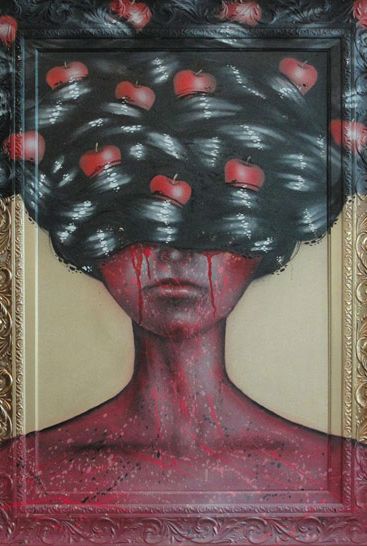

| Part of Castro’s Bob Bar solo exhibition “The Myth” |

Though graffiti is typically a masculine artform, it is also typically the expression of the oppressed. Graffiti has its roots in underprivileged, urban youth of color. Not only was graffiti a method with which these young men could articulate their individuality and their sense of repression, but it is also an anti-authoritarian type of protest. When considering Castro’s grafitti, this art-as-protest theme becomes particularly prominent because public spaces are so often unwelcoming for women, if not downright unsafe for them. This idea of reappropriating public space, of claiming space by marking it, customizing it, turning it into a reflection of the female self…is awesomely powerful.

|

| Panmela Castro signs her work Anarkia Boladona |

The short film lists some of the international accolades that have been bestowed upon Castro for her important work. In the end, Castro calls herself a “dreamer” and draws inspiration from one of her recurring character creations, Liberthé, who is “free in such an ample way that we can’t even imagine.” Castro’s artistic vision coupled with her vision for the global unity of women through grafitti art is subversive, beautiful, and just what we need. The idea that one woman acting out her dream can have a butterfly effect, causing revolution in the lives of other women around the world gives me hope. Castro brushes away the cobwebs of apathy and shows us that maybe we can make a meaningful change in our own lives and in the lives of other women, too, by just doing what we love.