|

| Movie poster for Spring Breakers |

|

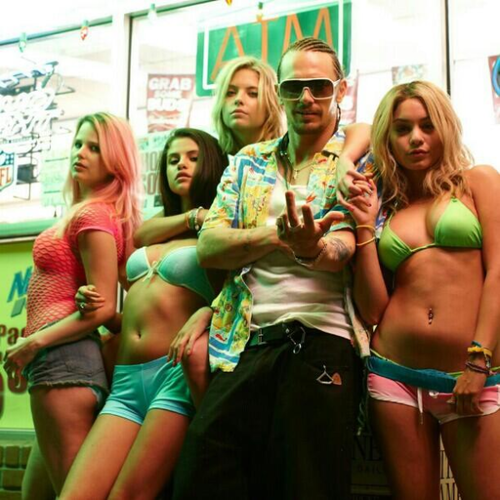

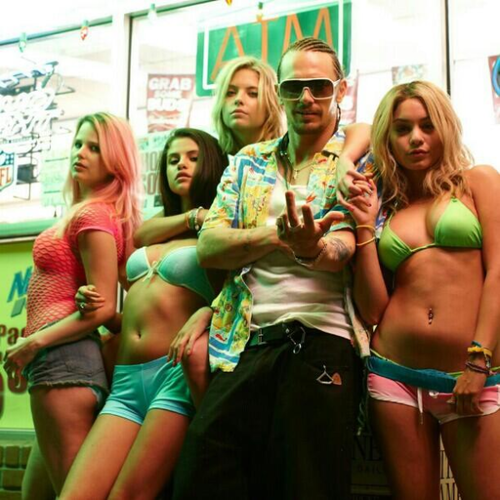

| Alien (James Franco) and his girls (l to r: Rachel Korine, Selena Gomez, Ashley Benson, and Vanessa Hudgens) |

The radical notion that women like good movies

|

| Movie poster for Spring Breakers |

|

| Alien (James Franco) and his girls (l to r: Rachel Korine, Selena Gomez, Ashley Benson, and Vanessa Hudgens) |

|

| Julia Roberts in Eat Pray Love |

The film follows Elizabeth “Liz” Gilbert, a successful writer with a seemingly perfect husband and home. Yet as she attains more and more of what she thinks she wants, Liz’s unhappiness grows and her world begins to crumble. Liz endures a devastating divorce followed by a fling with an actor. When that relationship falls apart, her pain consumes her and she’s unsure where to turn. Yearning to reignite her passion for life, Liz decides to travel, living abroad for one year. She chooses to live for four months in Italy to focus on pleasure (“eat”), then India to connect with her spirituality (“pray”) and finally Bali to learn how to balance the two and ultimately lead a life in harmony (“love”).

|

| Julia Roberts eating pizza in Eat, Pray, Love |

Lush and gorgeous, the film exhibits breathtaking vistas. It spurs you to want to pick up, leave everything behind and move to Italy, India or Bali. And megastar Julia Roberts is likable, capturing Gilbert’s curiosity about the unfolding world around her. My inner foodie enjoyed the decadent food scenes, which are a big part of the book, reminiscent of those in Julie and Julia. The film boasts a stellar supporting cast, particularly Viola Davis (love her), Mike O’Malley and Richard Jenkins. However, Javier Bardem’s talents are wasted here.

In the book, we have the pleasure of Gilbert’s humorous and vulnerable voice to guide us. While it’s sort of present in the film, it’s somehow diluted. One of the most heartbreaking yet touching moments for me in the book is when Gilbert sobs on her bathroom floor, begging god for help, as she doesn’t know what else to do. She prays that she’s not pregnant, even though she thinks a baby is what she’s supposed to want. Although the film sadly erases her pregnancy scare. I never felt, as much as she tried, that Roberts captures Gilbert’s depression and how she hit rock bottom.

I’m glad the movie retains the female friendship between Liz and Wayan as well as Wayan’s struggle to buy a house in Bali after she leaves her abusive marriage. But in the book, Gilbert spends far more time with Wayan and her daughter Tutti than the movie would lead you to believe, preferring to focus instead on the romance between Liz and Felipe, a Brazilian businessman in Bali.

Gilbert, with the help of friends and teachers along the way, finds the answers she seeks. Yet she also finds them within herself. But the film ignores this important distinction. Especially at the end, it’s as if Liz needs others to tell her what to do, rather than coming to decisions on her own accord. The book, while ending on a fairy-tale ending, focuses on Gilbert’s self-transformation, shifting from always revolving around a man to finding herself and what she wants. She realizes that you have to truly love yourself before you can love another. Gilbert learns to forgive herself, lets go of her unhappiness and embraces life.

|

| Eat, Pray, Love |

There’s a pervasive notion that women will go see movies in the theatre about men as well as films about women, while men will only go see films starring men. Women and Hollywood’s Melissa Silverstein writes about Eat Pray Love and how “if women like it, it must be stupid” all about how women’s stories and interests are devalued and treated as less important than men’s interests. Silverstein writes:

“Why is it that things that appeal to women are made to seem trivial, stupid and less than? Is it about the fact that large groups of women are embracing something? Is it a fear that if enough women like something we’ll figure out how screwed we’ve been on so many issues that we will all just come together and revolt? Pleeze. Newflash — we aren’t that organized. Shit, we buy more books and see more films, yet stuff that appeals to women is constantly demeaned. Aren’t our dollars as green as the guys?”

|

| Eat, Pray, Love |

In her articulate and fascinating Bitch Media article, “Eat Pray Spend”, Joshunda Sanders Diana Barnes-Brown look at the gender theme of Eat Pray Love in a different light. Talking about the book, they write about the pervasive problem of privileged literature (“priv-lit”), asserting that women like Gilbert, Oprah and other self-help gurus tell women to buy their way to happiness. She writes:

“Priv-lit perpetuates several negative assumptions about women and their relationship to money and responsibility. The first is that women can or should be willing to spend extravagantly, leave our families, or abandon our jobs in order to fit ill-defined notions of what it is to be “whole.” Another is the infantilizing notion that we need guides—often strangers who don’t know the specifics of our financial, spiritual, or emotional histories—to tell us the best way forward. The most problematic assumption, and the one that ties it most closely to current, mainstream forms of misogyny, is that women are inherently and deeply flawed, in need of consistent improvement throughout their lives, and those who don’t invest in addressing those flaws are ultimately doomed to making themselves, if not others, miserable.”

|

| Eat, Pray, Love |

While most people can’t jet off to Europe and Asia on a year-long trip (um, I sure as hell can’t afford that), I still think there are aspects of the film and Liz’s journey people can relate to. In addition to being eye candy, Eat Pray Love raises interesting questions about gender and expectations. Women are supposed to want marriage and babies. And yet what we want may differ from societal standards. Society rigidly dictates what women are supposed to want but may feel disillusioned when they achieve those goals and still aren’t happy. Too many women sacrifice their own happiness for others. There’s nothing wrong with putting yourself and your needs first.

Many people often let things hold them back from going after what they want. If people want to go back to school to earn their degree, they think they’re too old. If they want to travel, they think they don’t have the money or the time. As someone raised in a financially-struggling, working class household, who’s often worked two jobs to make ends meet, I’m well aware of the fiscal and time constraints in people’s lives. Yet I think Liz’s story is a testament to seize the moment, to pursue your passions. Walking away from the life you have always known to dare to try something different, to push yourself out of your comfort zone is not only daunting but incredibly brave.

|

| The story of Carrie, Miranda, Charlotte, and Samantha continued in Sex and the City 2 (2010) |

This is a guest post by Emily Contois.

I’m not embarrassed to admit it. I totally own the complete series of Sex and the City—the copious collection of DVDs nestled inside a bright pink binder-of-sorts, soft and textured to the touch. In college, I forged real-life friendships over watching episodes of the show, giggling together on the floor of dorm rooms and tiny apartments. Through years of watching these episodes over and over again, and as sad as it may sound, I came to view Carrie, Miranda, Charlotte, and Samantha like friends—not really real, but only a click of the play button away.

On opening night in a packed theater house with two of my friends, I went to see the first Sex and the City movie in 2008. Was the story perfect? No. But it effectively and enjoyably continued the story arc of these four friends, and it made some sort of sense. Fast forward to 2010 when Sex and the City 2 came to theaters. I had seen the trailer. I’ll admit, I was a bit bemused. The girls are going to Abu Dhabi? Um, okay. Sex and the City had taken us to international locales before. In the final season, Carrie joins Petrovsky in Paris and in this land of mythical romance, Mr. Big finds her and sets everything right. When their wedding goes awry in the first movie, the girls jet to Mexico, taking Carrie and Big’s honeymoon as a female foursome. But the vast majority of this story takes place in New York City. It’s called Sex and the City. The city is not only a setting, but also a character unto itself and plays a major role in the narrative. So, it seemed a little odd that the majority of the second movie would take place on the sands of Abu Dhabi.

|

| In Sex and the City 2, the leading ladies travel to Abu Dhabi |

Before the girls settle in to those first-class suites on the flight to the United Arab Emirates, however, we as viewers must suffer through Stanford and Anthony’s wedding. From these opening scenes, there’s no question why this dismal film swept the 2011 Razzie Awards, where the four leading ladies shared the Worst Actress Award and the Worst Screen Ensemble. How did this happen?? These four ladies were once believable to fans as soul mates—four women sharing a friendship closer than a marriage. And yet they end up in these opening scenes interacting like a blind group date—awkward, forced, and cringe-worthy.

From the moment our Sex and the City stars have decided to take this trip together, however, Abu Dhabi is viewed through a lens of Orientalism, demonstrating a Western patronization of the Middle East. Starting on the first day in the city, Abu Dhabi is framed derisively as the polar opposite of sexy and modern New York City. It’s also stereotypically portrayed as the world of Disney’s Jasmine and Aladdin, magic carpets, camels, and desert dunes—”but with cocktails,” Carrie adds. This borderline racist trope plays out vividly through the women’s vacation attire of patterned head wraps, flowing skirts, and breezy cropped pants. Take for example their over-the-top fashion statement as they explore the desert on camelback, only after they have dramatically walked across the sand directly toward the camera of course.

|

| Samantha, Charlotte, Carrie, and Miranda explore the desert, dressed in a ridiculous ode to the Middle East via fashion |

The exotic is also framed as dangerous and tempting, embodied in Aidan, Carrie’s once fiancé, who sweeps her off her feet in Abu Dhabi and nearly derails her fidelity. This plays out metaphorically as they meet at Aidan’s hotel, both of them dressed in black and cloaked in the dim lighting of the restaurant.

|

| Carrie “plays with fire” when she meets old flam, Aidan, for dinner in Abu Dhabi |

Sex and the City 2 also comments upon gender roles and sex in the Middle East. For example, in a nightclub full of belly dancers and karaoke, our New Yorkers choose to sing “I Am Woman,” a tune that served as a theme song of sorts for second wave feminism. As our once fab four belt out the lyrics, young Arabic women sing along as well. And yet the main tenant of the film appears to be an ode to perceived sexual repression rather than women’s rights.

|

| The ladies of Sex and the City 2 sing “I Am Woman” at karaoke in an Abu Dhabi nightclut |

Abu Dhabi is a place where these four women—defined in American culture not only by their longstanding friendship, but also by their bodies, fashionable wardrobes, and sexual exploits—must tone it down a bit. For example, Miranda reads from a guidebook that women are required to dress in a way that doesn’t attract sexual attention. Instead of providing any context in which to understand the customs of another culture, Samantha instead repeatedly whines about having to cover up her body. Our four Americans watch a Muslim woman eating fries while wearing a veil over her face, as if observing an animal in a zoo. The girls poke fun at the women floating in the hotel pool covered from head to ankle in burkinins, which Carrie jokingly comments are for sale in the hotel gift shop. In this way, Arab culture is both commodified and ridiculed. And rather than finding a place of common understanding, the American characters are only able to relate to Arab women by finding them to be exactly like them, secretly wearing couture beneath their burkas. While fashion is the common thread linking these American and Arab women, the four leading ladies don’t really come to understand the role and meaning of the burka. Instead, after Samantha causes a raucous in the market, the girls don burkas as a comedic disguise in order to escape.

At this point in the film, the main narrative conflict is again a very white problem—if the ladies are late to the airport, they’ll (gasp!) be bumped from first class. Struggling to get a cab to stop and pick them up, the women have to get creative. In a bizarre twist that references a scene from the first twenty minutes of the film, Carrie hails a cab by exposing her leg, as made famous in the classic film, It Happened One Night. While she gets a cab to stop, one is struck by the inconsistency. The women were just run out of town for Samantha’s overt sexuality and yet exposing a culturally forbidden view of a woman’s leg is what saves the day? Or is the moral of the story that a car will always stop for a sexy woman, irrespective of culture? Either way, our leading ladies make it to the airport, fly home in first-class luxury, and arrive home to better appreciate their lives. No real conflict has been resolved—though a 60-second montage provides sound bites of what each character has learned.

|

| In homage to It Happened One Night, Carrie bares her leg to get a cab to stop in Abu Dhabi |

Throughout the course of Sex and the City 2, the United Arab Emirates doesn’t fair well, but neither does the United States, as the land of the free and home of the brave is reduced to a place where Samantha Jones can have sex in public without getting arrested. Sex and the City 2 stands out as a horrendous example of American entitlement abroad, a terrible travel flick, and a truly saddening chapter for those of us who actually liked Sex and the City up to this point.

|

| Dorothy and friends skip to the Emerald City |

|

| “Wait – I thought it was a trip, but I was really just tripping?” |

|

| Dorothy yearns for life somewhere over the rainbow |

|

| Dorothy and her three best friends |

|

| Geena Davis as Thelma and Susan Sarandon as Louise |

After its release in 1991, Thelma & Louise stirred up controversy mainly surrounding its connection to feminism, its use of violence, and its presentation of male characters.[i] It was criticized for its portrayal of men as one-dimensionally negative. The two heroines were accused of male bashing. It was condemned for advocating violence as a solution to women’s problems. Over twenty years later, though, I think that Thelma & Louise is most often thought of as a wild, raucous outlaws-on-the-run movie, but with girls. A buttered-popcorn, butt-kicking chick flick about female empowerment. Two strawberry blondes in a sea-foam T-bird convertible. Lite feminist fizz.[ii] It’s unthreatening. And yet, it threatens me.

I find it deeply and profoundly scary.

Chrissy and I watching it, drinking whole bottles of vodka in my studio on Mission Street. Her curly hair/my straight hair.

We called it a horror movie.

Because of the end. Because they almost made it. Because they maybe could’ve made it. Because they never could’ve made it. Because the world we live in wouldn’t have let them. And because they knew it.

|

| Still from Thelma & Louise |

It threatens me because it happens in my world too. It obscures my view.

When Thelma says shouldn’t we go to the police & Louise says we just don’t live in that kind of world.

When Thelma says how do you know ‘bout all this stuff anyway.

When Thelma says it happened to you, didn’t it.

The trail of breadcrumbs starts with rape & the thread is a product of rape.

They follow the thread in circles, refusing to go through Texas.

|

| Still from Thelma & Louise |

In Europe when Jenny and I slept in the same bed every night even though there were two.

How in Spain Lana and I would sit in coffee shops for hours and get drunk on the beach and take pictures in Zara.

When we were in Western Mass and Tina brought me to the train and I didn’t want her to leave.

|

| Geena Davis as Thelma in Thelma & Louise |

|

| Thelma and Louise being pursued by police |

If men didn’t rape, Louise wouldn’t have shot the rapist. If the system didn’t blame rape victims, they wouldn’t have gone on the run. If men didn’t rape, they could have driven through Texas. If the system didn’t blame rape victims, Louise wouldn’t have been so afraid. If women weren’t taught they deserve to be treated like shit, they wouldn’t have had to become fugitives in order to feel free. If there was a place for liberated, powerful women who live on their own terms in this world, they wouldn’t have had to create their own. If there was a place for liberated, powerful women who live on their own terms in this world, they wouldn’t have had to plummet into the Grand Canyon in order to feel free.

The logic falls in on itself. Like a sea-foam T-bird falling into the Grand Canyon.

When there’s a wall of cop cars behind them and the canyon is in front of them and Thelma says let’s keep goin’.

|

| Thelma with a gun |

It shows the car falling all the way into the canyon instead of freezing the frame with the car in mid-air, flying outward on an upswing. Watch it. Because you can see the car getting smaller and smaller, as the canyon gets bigger and bigger. And it starts falling at an angle that no longer looks controlled, no longer looks triumphant. Which is exactly how it should look — the logical conclusion that joyful, strong women have no place in this world.

The way they freeze the frame with the car on an upswing at the end is why people call Thelma & Louise a “chick flick.” It’s why it’s remembered as a girl power-powered outlaw movie, rather than a horror one.

How me and Carrie wrote a song about Kim while she was in the other bedroom.

When Tina and I were drinking sangria in San Francisco, and we couldn’t stop prank-calling you and laughing into our sleeves.

How we were in the Catskills and I yelled at Janie, well why don’t you just eat.

|

| Louise with a gun |

Before the credits start to roll, the white screen flashes with a montage of images showing the two women, happy and alive, suggesting a weird kind of magical realism.

It’s all in that phrase: let’s keep goin’. As if by driving off the cliff they really did keep going. As if they had reached a parallel universe in which their journey did not have to end. It reminds me of the end of Pan’s Labyrinth, before the little girl is shot in the labyrinth. In the scene where we see her stepfather watching her talking to thin air, we see a crack in the magic into a horrific reality. The last scene in Thelma & Louise shows no definitive cracks in the magic. Only a triumphant freeze-frame that loops back almost instantly to images of the heroines’ lives.

I think, for instance, of two movie heroines, born-again desperadoes, who smash one limit after another, uncover the hidden places where anger and despair, defiance and love converge, and finally leap into the Grand Canyon because freedom’s just another word for nothing left to lose.

I can’t decide if I think Willis is letting the film off too easy here, but I love this comparison anyway. Janis Joplin was real; her struggle was real and her death was real. But for me, growing up in the 80s and 90s, she wasn’t a real woman so much as an icon; a symbol of wild, defiant love and art, tough, complex femininity and unrelenting sexuality, her life remembered for the spirit of freedom that she embodies, rather than for the sense of tragedy. And so are Thelma and Louise, for better or for worse — their car still goin’, the music still blasting, the camera still clicking images of them, first in red lipstick, sunglasses and hair kerchiefs, and later in dirtied jeans and cut-off t-shirts, their hair whipping wildly in the wind.

|

| Thelma & Louise DVD cover |

[ii] “Light feminist fizz” is borrowed from Bill Cosford, Miami Herald movie reviewer

[iii] Roger Ebert, “Thelma & Louise,” Chicago Sun-Times

[iv] Ed. Nona Willis Aronowitz, Out of the Vinyl Deeps: Ellen Willis on Rock Music, University of Minnesota Press