Tag: Theme Month

Buffy the Vampire Slayer Week: Buffyverse Season 5 Trailer

Buffy the Vampire Slayer Week: Xander Harris Has Masculinity Issues

|

| Xander Harris (Nicholas Brendon), cavalry guy with a rock (not pictured: rock) |

|

| Seriously? This guy? |

|

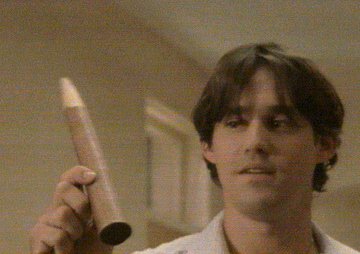

| Xander and a phallic symbol. He has a complicated relationship with these things. |

|

| Xander and his father (Michael Harney) |

|

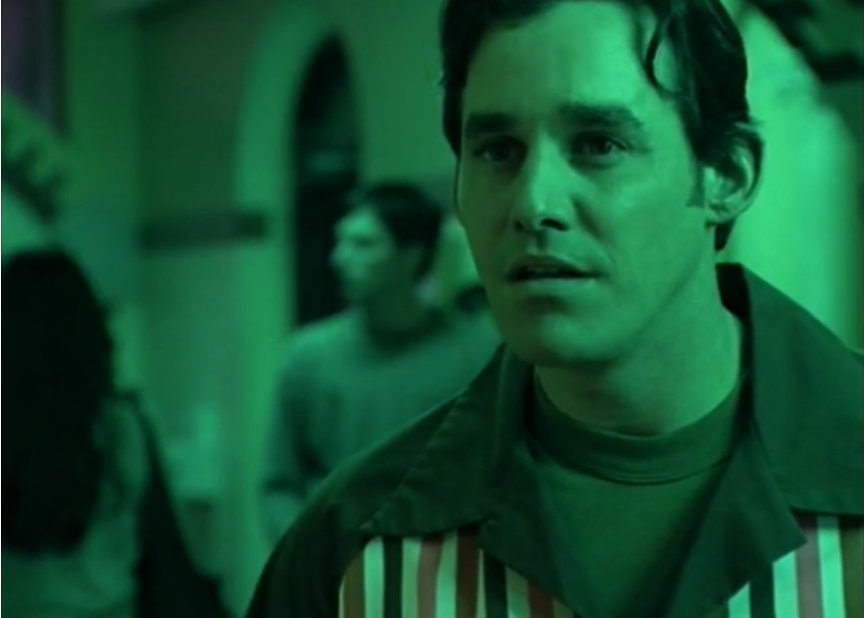

| Xander is confused. He gets that way a lot. |

|

| Who says his Snoopy Dance isn’t manly? |

|

| Xander and Cordelia (Charisma Carpenter), his original acid-tongued sweetheart |

|

| Xander embraces his comfortador role, helps Willow (Alyson Hannigan), and saves the world with a hug. |

Lady T is an aspiring writer and comedian with two novels, a play, and a collection of comedy sketches in progress. She hopes to one day be published and finish one of her projects (not in that order). You can find more of her writing at The Funny Feminist, where she picks apart entertainment and reviews movies she hasn’t seen.

Buffy the Vampire Slayer Week: Equality Now: Joss Whedon’s Acceptance Speech

A year before that announcement, Joss Whedon, the creator of such women-centric television shows as Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Firefly, and Dollhouse, accepted an award from Equality Now at the event, “On the Road to Equality: Honoring Men on the Front Lines.”

Buffy the Vampire Slayer Week: Femininity and Conflict in Buffy the Vampire Slayer

|

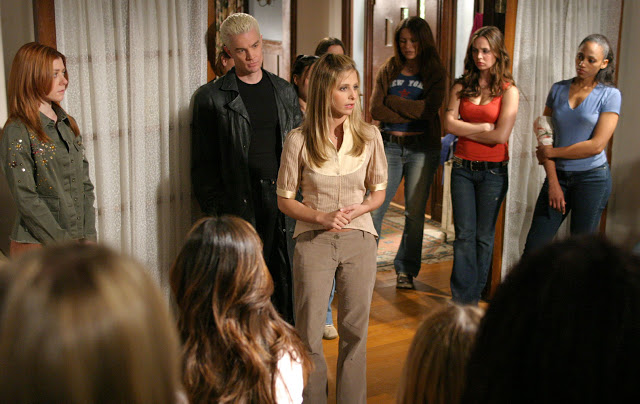

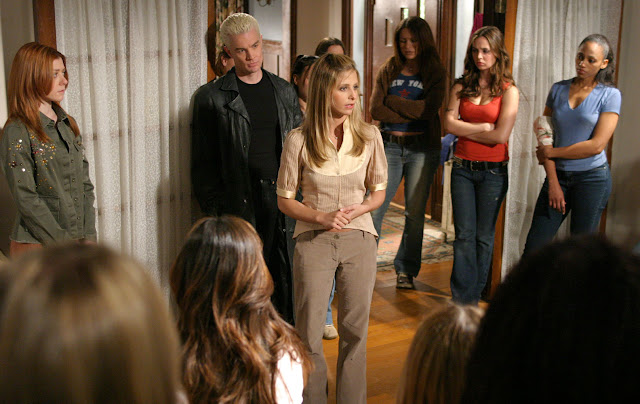

| Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Season 7 |

|

| Sarah Michelle Gellar as Buffy, looking pouty in a halter top |

Deborah Tannen explains the way in which women are denied a “default” state in the way they dress and portray themselves, stating that “if a woman’s clothing is tight or revealing (in other words, sexy), it sends a message… …If her clothes are not sexy, that too sends a message, lent meaning by the knowledge that they could have been” (622). If Buffy were portrayed as butch, she would just be a girl pretending to be a man. If she were portrayed as too vanilla in the way she dressed, spoke, and acted she would be less interesting; her plainness would also send a message to the viewer by making her more androgynous. Buffy may be saucy and sexy and contrived in the way she dresses, but that is part of what makes her character complex. She is a warrior but also, undeniably, a woman.

Thus it is interesting that the plot and dialogue of the show often does not reinforce Buffy’s feminine dress as a positive thing, but instead condemns her for it. In the episode “Bad Eggs” Buffy and her mother are shopping and Buffy wants a new outfit. Joyce says no, “it makes you look like a streetwalker”. Buffy pouts and replies, “but a thin streetwalker, right?” This scenario is sadly common. Buffy’s peers, her mentors, and authority figures criticize her appearance as if it were offensive, and Buffy deflects such comments with sarcasm instead of defending her right to determine her own physical appearance.

|

| Buffy working at Double Meat Palace |

As the show progresses and Buffy moves out of high school and into college and pursuing a career, she continues to encounter difficulty in her everyday life because of the dual identity slaying forces her to concoct. When her mother dies Buffy takes on the role of provider for her household. Buffy works a minimum wage job at Double Meat Palace to make ends meet as she is incapable of securing better employment. Buffy is eventually offered a position as a school counselor by the new principal in town, Robin Wood. In the episode “First Date” Principal Wood reveals that he knows that Buffy is the Slayer, and this is why he offered her a job. Buffy says, “so you didn’t hire me for my counseling skills?” and Principal Wood responds with a chuckle. Buffy may be powerful as the Slayer, but as a provider for her family and as an employee, her skills are portrayed as laughable.

Buffy’s necessary efforts to cloak some of her actions and engage in subterfuge to protect those unaware of vampires also constantly weaken her standing in society. Dramatic irony is often engaged as a plot device in BtVS, wherein Buffy is posed almost clownishly trying to hide the truth from an ignorant and often judgmental public. It is humorous as well as endearing to see how poorly Buffy lies, and Buffy’s lack of finesse outside of slaying does lend her character a great deal of humanity. Yet one must question why dramatic irony so often has Buffy playing the part of the bozo. Buffy is too often percieved of as flaky, inconsistent, or downright delusional. As one character says, a lot of people think Buffy “is some kind of high-functioning schizophrenic” (“Potential”). While Buffy may be possessing of super-human strength and a higher calling, it greatly impedes her ability to function as a normal member of society. She faces humiliation, prejudice, and conflict on a daily basis.

|

| Buffy and her mother Joyce |

As the series progresses Joyce becomes portrayed as less neglectful, but in the first few seasons especially there are serious questions to be asked about her role as a mother. She has a teenage daughter who sneaks out nightly, lies to her, skips classes and bucks authority and Joyce is largely incapable of informing her daughter’s actions. Much of the early dynamic between mother and daughter comes down to the fact that Joyce does not realize the reality of Buffy’s “dual identity as Slayer and Student… a greater failing than Lois Lane’s traditional inability to envision Clark Kent without his glasses” (Williams, 64). The fact that Joyce is kept ignorant and Buffy routinely shuns her mothering is not entirely Joyce’s fault. The Slayer cannot respect her mother’s authority because the Slayer’s role is more important than mother-daughter relations.

|

| Buffy and Angel |

Buffy’s later relationships may not be equally as tormented in terms of scale, but they do continue to revolve around themes of pain and conflict. This conflict is evident not only in romantic relationships, but in all her close relationships with men. Buffy even comes to blows with her mentor, Giles. While often their fighting is only in words, twice she resorts to hitting him. The first time occurs in the final episode of season one, “Prophecy Girl.” When Buffy realizes that Giles is going to sacrifice himself to save her life, she knocks him out in order to protect him. This action does lead to Buffy’s death by drowning, but she is resuscitated by her close friend Xander. The second time Buffy punches Giles echoes the first. In “Passion,” Giles is inflamed with rage after Angelus kills the woman Giles loves. Giles pursues Angelus in a suicidal rage. Again, Buffy resorts to blows in order to get through to Giles where words failed, to save his life. No matter how close the relationship, how deep the trust between two people, Buffy always seems to have to resort to her role as Slayer and her superhuman powers in order to make herself heard. This repeated theme has a serious connotation; Buffy as a girl is powerless. Her authority is intrinsically tied to her physical strength, which comes from her role as Slayer.

|

| From the episode “Hush” |

Often Buffy resorts to saying “I’m the Chosen One” when her authority is questioned; she is the Slayer, and that truth defines the way in which she acts and relates. Because of her power Buffy is forced to struggle in every area of her life. What message does this send to a young girl watching the program who is imagining being as powerful as Buffy? Rather than being an encouragement for girls to picture themselves as superheroes as boys so often do, BtVS sends the opposite message. Don’t pursue power, because that power will define your circumstances and those circumstances will define you. You will be forced to lie, to cheat, to sacrifice healthy relationships and to face constant conflict as a result of your independence.

It is unfortunately true that many shows that feature women as primary characters employ the same kind of storytelling. Xena: Warrior Princess, La Femme Nikita, The Closer, Alias, In Plain Sight, Saving Grace, Weeds and Battlestar Galactica all feature women as primary characters. All of the women in these shows have just a few things in common aside from their beauty: their intelligence and capability is challenged regularly; they face conflict in their private lives and homes; and they are punished for their physical and emotional strength. It is almost inevitable that any strong woman on TV would face the same treatment, especially those who play a traditionally masculine role. Starbuck from Battlestar Galactica, Xena, Nikita, Sidney Bristow of Alias, Mary Shannon of In Plain Sight and The Closer’s Brenda Lee Johnson all play traditionally masculine roles. All of those women face conflict and physical violence in almost every episode. Not only do they have to fight for respect, but their good works are seldom rewarded. Appreciation, respect, achievement, and victory are few and far between and must be won at high cost; home is not often a safe haven and interpersonal relationships are constantly disrupted. What is true for all of these female characters is especially true in the case of Buffy; she is a singular icon for female strength as well as for the punishment of feminine power.

|

| Buffy and Faith |

Male Superheroes do not receive the same treatment. Spiderman, Batman, and Superman may engage in conflict in their everyday lives as a result of their necessary deceptions, but it is certainly not to the measure which Buffy does; their familial ties are free from extreme stress. They all have close relationships with older figures who mentor them and preserve their familial ties (Aunt Mae, Alfred, and the Kents respectively). They have places they can go home to which are a respite from the pressures their dual identities create. Each of the male superheroes mentioned also receives a certain measure of success both in their chosen careers outside of crime fighting and their romantic lives. While Batman does not have any long term romantic relationships, he is a millionaire and dates often; he is rewarded for his power. Buffy is not afforded the kind of pleasures these male superheroes enjoy. It is because of that truth that Buffy’s story is far from empowering. Rather than showcasing a character who has achieved full agency as a woman and been rewarded for it, Buffy the Vampire Slayer instead chronicles one girl’s fight to be respected; a fight it sometimes seems she will never win.

The fact that women receive unequal treatment in today’s society is made wholly apparent in the fact that feminine strength is not showcased or rewarded in television media as masculine strength always has been. Until women are allowed to be feminine and strong without fear of their homes and lives being disrupted, or facing constant judgment and critical backlash, women will remain less than men. While Buffy the Vampire Slayer may have gone further than any show before it in creating a female character who was independent and powerful, the fact that her strength could not go unpunished leaves a gaping hole. Young women are still hungry for a role model who can navigate all of the complexities of modern womanhood successfully. Buffy’s final fight, the fight for respect, must not be left unwon. It’s time for a female superhero to get equal treatment: strength, intelligence, achievement, and reward.

http://www.rebelliouspixels.com/2009/buffy-vs-edward-twilight-remixed viewed 10/28/11

Early, Francis. “Staking Her Claim: Buffy the Vampire Slayer as Transgressive Woman Warrior.” Journal of Popular Culture 35.3 (2001): 11-17.

Jewett, Lorna. Sex and the Slayer: A Gender Studies Primer for the Buffy Fan. Middletown: Wesleyan, 2005. Print.

Magoulik, Mary. “Frustrating Female Heroism: Mixed Messages in Xena, Nikita, and Buffy.” Journal of Popular Culture 39.5 (2006): 729-55.

Tannen, Deborah. “There is No Unmarked Woman.” Signs of Life in the USA: Readings on Popular Culture for Writers. Ed. Sonia Maasik and Jack Solomon. 6th ed. Boston: Bedford St. Martins, 2009. 620-24. Print.

Whedon, Joss. Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Seasons 1-7. Television Program.

Williams, JP. Fighting the Forces: What’s at Stake in Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Ed. Wilcox, Rhonda, and David Lavery. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield, 2002. 61-68. Print.

———-

Buffy the Vampire Slayer Week: Buffyverse Season 4 Trailer

Quote of the Day from "When TV Became Art: What We Owe to Buffy" by Robert Moore

|

| Buffy on the verge of killing a vampire |

In an article published way back in 2009, Robert Moore made the case in PopMatters for why Buffy the Vampire Slayer is such an important television show:

Without any question, Buffy revolutionized the role of women on television, more even than Mary Tyler Moore or Cagney and Lacey or Murphy Brown or Ally McBeal. If you look at female heroes (as opposed to hapless heroines–I have always thought that the definition of heroine should be “endangered female in need of rescue by male hero”) in the history of TV, you will be astonished at how few there are prior to the nineties. You have Annie Oakley in the fifties and Emma Peel on The Avengers in the sixties, and to a degree Wonder Woman (who spent a great deal of her time worrying about impressing her boss Col. Steve Trevor) and The Bionic Woman (the weaker spin off to The Six Million Dollar Man). This all changed in the nineties, first with Dana Scully on The X-Files and then with Xena. But the former, as competent as she was as an FBI professional, was not sufficiently iconic to change TV, while the latter, sufficiently iconic, was too cartoonish to inspire future female heroes. Buffy was the turning point. You can write the history of female heroes on TV as Before Buffy and After Buffy. It is not a coincidence that most of the female heroes on TV arose in the wake of the little blonde vampire slayer. Look at the roster: Aeryn Sun (Farscape), Max (Dark Angel), Sydney Bristow (Alias), Kate Austin (Lost), Kara “Starbuck” Thrace (along with a plethora of other strong women on Battlestar Galactica), Olivia Dunham (Fringe), Sarah Connor and Cameron (Terminator: The Sarah Connor Chronicles), Veronica Mars, and an almost uncountable number of lesser characters. Buffy made TV safe for strong women. This isn’t art, but it is the content of art. Buffy guaranteed that TV as art would make a place for heroic women.

Buffy the Vampire Slayer Week: Death Is Your Gift–In Praise of Buffy the Vampire Slayer’s Fifth Season

|

| Buffy, jumping off the ledge in Season Five |

There are plenty of reasons why Buffy doesn’t often get recognised as the masterpiece of a show that it was. All the really great television series of the last fifteen years or so have been serious, downright worthy affairs and critics have taken them very seriously in turn. Buffy took itself very seriously indeed too, but there was always a deliberate, inherent silliness in its central premise that turns many people off before they even give it a chance. Furthermore, my belief that it’s one of the greatest shows of all time doesn’t mean I’m not fully aware that it has its fair share of dud episodes – such is the curse of the 22 episode season and the way the show figured itself out as it went along.

But its strengths are strengths that none of the other big US dramas have. For one, the flexibility of its form meant that it could be any kind of show it wanted: one week it’s a goofy comedy, the next it’s a frightening fairy tale, the week after it’s an all-singing all-dancing musical. It was clearly the work of a team of writers, too, and when I was young and watching it for the first time it was the first time I really started to learn how TV was constructed – I got a thrill from seeing who had written each episode and guessing at what kind of episode it was going to be by who wrote it. Above all, though, the thing that Buffy has in spades that most shows lack, and the aspect of the show that season five best showcases, is emotion. Even at its most laid back, Buffy is a show spilling over with emotion, and it’s this that gives the potentially goofy premise of show its weight. Whedon et. al. were absolute masters at making us really care about their characters, and every audacious plot contrivance was easily swallowed when viewed through the lens of the real, human emotion that they would imbue it with.

Take, for example, season five’s biggest plot contrivance – Dawn’s sudden appearance as Buffy’s sister. She’s never been mentioned or seen before, everyone’s acting as if he’s been there all along, and aside from one crazy tramp seething at her that she doesn’t belong here, we the audience aren’t given many clues as to who or what she is for six entire episodes. When we do find out what she is – a mystical key sent to Buffy and her friends to protect, complete with fabricated memories so she’d love her deeply like a sister – it doesn’t come easy, and doesn’t make things any less complicated. Many people call Dawn the albatross of the season, but while her character becomes much more problematic later on the series’ run, I think she works beautifully in this season. Moments like the one where Joyce realises what Dawn is and loves her anyway, or when Buffy talks to her about how they share the same blood, are some of the most beautifully drawn and tender moments the series ever produced, and if she hadn’t been there the show would have been drained of all its agency.

If I was going to pin the blame on any character for dragging down the season in its early episodes, it would be Riley. From the outset of the season it’s clear that the writers don’t really know what to do with him now that the Initiative business from Season Four is done and dusted, but they take an awfully long time to get rid of him. I’m sure that the plotline in which his insecurities at no longer being a superman lead to him going to some kind of vampire sucking den for cheap thrills looked good on paper, but it sticks out like a sore thumb in a season that’s otherwise thematically harmonious. In a season that’s more about confronting the hard-edged reality that our heroes ignore by fighting monsters, this slightly hysterical flight-of-fancy just doesn’t work.

That’s a small quibble, though, when you’re faced with a season of television that’s otherwise so thematically rich and intricate. All the themes and motifs of the series – family, power, blood, death, the toll being a slayer takes on Buffy’s loved ones – all bounce off one another in constantly fascinating ways.

Take, for example, the season opener, “Buffy vs. Dracula.” At first glance it’s a fun, punchy, exciting opening to the season, but in retrospect it kicks into gear a lot of what season five is trying to do. To begin with, there’s a renewed focus on Buffy’s blood as something powerful and life-giving, an idea that is teased throughout the season but doesn’t come to fruition till its final moments. Most importantly though, it ups the stakes and deepens the mythology significantly. Season Four’s closer “Restless” did a great job of connecting the slayer to a deep and ancient power, but it’s in “Buffy vs. Dracula” that she sets out to learn what that means, tasting the darker side of her power and asking Giles to help her harness it.

Perhaps that’s why this season feels so different to what came before it. Everything feels grander, more important, like the writers are making the show they’ve been preparing for all this time. They have more confidence than ever in the story they want to tell – early on in the season they drop the college as the show’s hub, instead centering on Buffy’s two families: her mother and sister at home, and her friends at the Magic Shop. It results in the season being far more streamlined and the overarching plot having far more prominence – there are few episodes that have no connection to what’s going on with Glory and Dawn, and even the most inconsequential-seeming episodes – “Triangle” and “I Was Made to Love You” – have things in them that become important later. Many people miss the one-off, monster-of-the-week aspect of the show from season five onwards, but I always found that Buffy worked best when it was dealing with more long-form, character-based storytelling, and season five’s arc has to be its strongest.

|

| Willow and Tara sharing their first kiss in Season Five |

And then there’s “The Body.” To say that “The Body” is a great episode of television would be an understatement. It’s one of the most ambitious, devastating, daring and powerful things ever committed to the small screen, saying more about death and grief in one episode than Six Feet Under managed in its entire run and looking and feeling unlike anything I’ve ever seen before or since – including any other episode of Buffy. Using no non-diagetic music and limiting each act to just one scene, Whedon tracks Buffy’s loss of her mother with stark, hyper-realist immediacy. People are quick to criticise Sarah Michelle Gellar’s acting ability, but she does great work here, and her journey from blind panic and fear to numb, empty grief is devastating to watch. So many tiny moments stand out from the episode’s first act alone – Buffy rearranging her mother’s skirt before the paramedics enter; the strange, unclear way she says “She’s at the house” to Giles on the phone; the moment when she opens her backdoor and peers out into bright sunlight and the world still going on outside – but the episode’s best moment is the scene where Buffy’s friends each go through their own grief. Willow frets about what clothes she should wear while Tara comforts her (with what was their first on-screen kiss despite them having been a couple for over a year), Xander punches a hole through the wall, and Anya asks a lot of questions. Anya’s recently-mortal status has been a bottomless well of comedy since she became a regular cast member, but here she surprises everyone and gives a speech that’s unbearably sad: “She’ll never have eggs, or yawn or brush her hair, not ever, and no one will explain to me why.” The gang have faced all kinds of insurmountable odds, but when faced with the cold hard reality of death, none of them has the answers.

|

| Anya in tears after the death of Joyce |

So, while conventional wisdom will cast season 3 as Buffy’s finest year, and many will cite Season 2’s Angel-turns-evil plotline as the show’s most operatic, emotional arc, I respectfully disagree. Season 3 is terrific fun, and Angel’s transformation is as sensational and rewarding a plot twist as they come, but Season 5 has both four years of history behind it and a committed drive to produce something more daring and ambitious than ever before. Its influence is still being felt now: without Buffy, there’d be no Lost, no 24, no new Doctor Who, and yet none of its many protégées has ever come close to the emotional gut-punch of Buffy jumping off that ledge. If you’re ever left wondering why Buffy the Vampire Slayer has such a huge cult following a decade later; if you’re baffled by why someone would bother to write 2,000 words about it in 2012; mark my words: you are missing out.

———-

Buffy the Vampire Slayer Week: Willow Rosenberg: Geek, Interrupted

|

| Willow Rosenberg (Alyson Hannigan) on Buffy the Vampire Slayer |

|

| Willow (Alyson Hannigan) talks to Buffy (Sarah Michelle Gellar) |

|

| Willow possessed as she performs the spell |

|

| Willow’s spell goes wrong |

|

| Dream-Willow delivering a book report |

|

| Willow talks to Buffy after coming down from a high |

Lady T is an aspiring writer and comedian with two novels, a play, and a collection of comedy sketches in progress. She hopes to one day be published and finish one of her projects (not in that order). You can find more of her writing at The Funny Feminist, where she picks apart entertainment and reviews movies she hasn’t seen.

Buffy the Vampire Slayer Week: Buffyverse Season 3 Trailer

Reminder: Buffy Theme Week Deadline — Friday at Midnight!

|

| Cast of Buffy the Vampire Slayer |

–We like most of our pieces to be 1,000 – 2,000 words, preferably with some images and links.

Women in Science Fiction Week: The Roundup

The wonderful thing about science fiction is that the writers have the opportunity to create a world, which while based on ours, can be markedly different. This means that there should be a place for strong female characters who are not restricted by sexism or forced into a situation in which they must perform femininity on a daily basis to be accepted as ‘woman.’ Despite the freedom of this genre; however, nothing is born outside of discourse, which means of course that we end up with the same sexist tropes repeatedly.

Even in shows which readily lend themselves to recurring scenes of violence, because women have historically been framed as delicate and passive, men end up in the leadership roles. This also means that when the action does finally happen, women are placed into nurturing roles like doctors and nurses to aid the wounded men. While some may see this exchange as complementary, it in fact sets up a serious gender divide that is reductive.

The lack of representation of older black women in science fiction is coupled with a complete lack of interest in developing any kind of independent agenda for their characters. Guinan in Star Trek: The Next Generation and the Oracle in The Matrix, the only two named older black women that I (or anybody else that I asked) could think of, are recycled wholesale from the stereotypical mammy of the slave era.

The main features of the stereotypical mammy are grounded in a white fantasy; often these women were wet nurses, bringing up their white charges in a far more intimate relationship than either have with their biological families. It is not Scarlett O’Hara’s mother who fusses about her eating habits, does up her dress, or worries about her relationships. It is Mammy. Scarlett, and the viewers of Gone With the Wind, never consider what Mammy might think of their relationship, or worry that she might have children of her own whom she cannot raise. We are content to construct a fantasy in which Mammy wants nothing more than to feed, clothe and care for her white charge.

It’s assumed that, of course we want Cobb to win because he’s really Leo, and, you see, Leo is talented but Troubled. What troubles him? You guessed it: a woman. A woman whose very name–Mal (played by Marion Cotillard, an immensely talented actress who’s wasted in this role)–literally means “bad.” Who or what will rescue Cobb/Leo from his troubles? You guessed it again: a woman. This time, it’s a woman whose very name–Ariadne (played by Ellen Page in a way that demands absolutely no commentary)–means “utterly pure,” and who is younger, asexual (a counter to Mal’s dangerous French sexuality) and without any backstory or past of her own to smudge the movie’s–and her own–focus on Cobb/Leo. So, it’s not a stretch here to say that Cobb needs a pure woman to escape the bad one. Virgin/whore stereotype, anyone?

For me, I can’t separate Alien and Aliens (although I pretend the 3rd and 4th don’t exist…ugh). Both amazing films possess pulse-pounding intensity, a struggle for survival, and most importantly for me, a feminist protagonist. Radiating confidence and strength, Ripley remains my favorite female film character. A resourceful survivor wielding weapons and ingenuity, she embodies empowerment. Bearing no mystical superpowers, she’s a regular woman taking charge in a crisis. Weaver, who imbued her character with intelligence and a steely drive, was inspired to “play Ripley like Henry V and women warriors of classic Chinese literature.”

Sigourney Weaver’s role as Ripley catapulted her to stardom, making her one of the first female action heroes. Preceded by Pam Grier in Coffy and Dianna Rigg as Emma Peel in The Avengers, she helped pave the way for Linda Hamilton’s badassery in T2, Uma Thurman in Kill Bill, Carrie-Anne Moss in The Matrix, Lucy Lawless as Xena, Sarah Michelle Gellar as Buffy, and Angelina Jolie in Tomb Raider and Salt. But Ripley, a female film icon, wasn’t even initially conceived as a woman.

Overall, Olivia Dunham is a prime example of what it is to be a heroine in a science fiction world. She can break bones, witness the aftermath of a gruesome fringe event without batting an eye, and go toe-to-toe with mastermind villains, and yet she is not invincible or impervious to emotional situations. Although she is constantly surrounded by extraordinary events and weird circumstances, she is a truly believable character, imbued in verisimilitude. With a fifth season on the horizon (slated for September), I cannot wait to see what is in store for Olivia and her team.

Joss Whedon is known for creating and writing about strong female characters in his science fiction shows. One of the most popular and complex of these characters is Willow Rosenberg from Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Willow speaks to many people and quite a few have named her their favorite character on the show, from Mark at Mark Watches to Joss Whedon himself, who put the most Willow-centric episode of the series (“Doppelgangland”) on his list of favorite episodes.

Another thing that makes Willow so appealing is the fact that her character arc over seven seasons can’t be described in only one way. Some see Willow’s story as a shy, brainy computer geek embracing her supernatural power in becoming a witch. Others relate to her arc as one of a repressed wallflower who explores her sexuality and finds more confidence in coming out as a lesbian. Still others are fascinated with the different ways she handles magic, and her recovery after drifting too far to the dark side.

What story is told when those three arcs are put together? For me, the story of Willow Rosenberg is the story of a woman who spends years defining and re-defining herself, rejecting roles that other people have chosen for her – for better and for worse.

As much as I would like to sit through a movie like this and enjoy it for what it is (ground-breaking sci-fi entertainment that will go down in history), I simply can’t. James Cameron’s attempt to create a more spiritual, natural, and peaceful society leaves me annoyed that once again this idea is filtered through a white, Western, male member of a patriarchal society. Some theorists will consider Cameron’s Alien trilogy feminist, because of Sigourney Weaver’s empowered Ripley (legend says it was written to be asexual–with casting deciding the character’s sex), but she still has to prove her femininity and womanliness by saving cats and small children. I fear that many feminists will laud Avatar as well–for creating a world where the people worship a female entity (“Eywa”), because the Clan leader’s female mate/wife is as powerful as him, and since the female lead is as empowered as Ripley. However, like Ripley, Neytiri too has her feminine trappings, as her power can be explained away through her heritage.

Patriarchy perpetuates rape culture and infringes on reproductive rights. Alien centered on rape and men’s fear of female reproduction. Littered with vaginal-looking aliens and phallic xenomorphs violating victims orally, these themes resurface. But this time around, Scott’s latest endeavor also adds abortion and infertility. As ThinkProgress’ Alyssa Rosenberg asserts, Prometheus bolsters the Alien Saga’s themes of “exploration of bodily invasion and specifically women’s bodily autonomy.”

[…]

But David doesn’t want her to have an abortion, insisting she be put in stasis and trying to restrain her. Like Ash in Alien, it appears David had an agenda to try and keep the creature inside Shaw alive. David tries to thwart Shaw’s agency and bodily autonomy, forcing her to remain pregnant. Hmmm, sounds eerily similar to anti-choice Republicans with their invasive and oppressive legislation restricting abortion. No one has the right to tell someone what to do with their body.

Lost has many strong female characters, many of whom I could easily see wearing a “This is what a feminist look like” t-shirt. As noted by Melissa McEwan of Shakesville, an admitted Lost junkie, “Generally, the female characters are more well-rounded than just about any other female characters on television, especially in ensemble casts.”

Lost has often presented ‘gender outside the box’ characters, suggesting being human is more important than being a masculine man or a feminine woman. After all, when you are fighting for your life, ‘doing gender right’ is hardly at the top of your priority list.

While Jack and Sawyer try to out-macho each other in their love triangle with Kate, neither hold entirely to the Rambo-man-in-jungle motif. As for the women, they just might be the strongest, bravest, wisest female characters to grace a major network screen since Cagney and Lacey.

Though the island is certainly patriarchal, one could make a strong case that male-rule is not such a good thing for (island) society. Kate or Juliet would be far better leaders than any of the island patriarchs (and as some episodes suggest, would make great co-leaders – what a feminist concept!)

But the film stars another woman, albeit in a more supporting role within the cast: Kirsten Dunst, who gives a sensitive portrayal of Mary, a character who is in many ways the polar opposite of Clementine. Mary is quiet, almost mousy. She wears rather plain, unobtrusive clothes. At work, she wears a smart white lab coat, as if to reinforce the medical nature of the proceedings, and answers the phone in the same measured tone of voice, responding to all queries with variations on the same stock phrases. Her inner extrovert manifests only after a combination of alcohol and pot, which lead her (and Stan) to have a wild dance party, including jumping half-dressed on the bed while Joel’s memory is being erased. Mary is, however, a woman who knows her own mind as the film progresses. She exchanges her seemingly blind devotion to Lacuna and Dr. Mierzwiak for her own brand of individual agency. By the end, it’s clear why: Mary has had her memory altered by Dr. Mierzwiak, after what appears to be some convincing on his part, when the affair they’d been having was discovered by his wife. The knowledge, if not the memory, of this seems to jolt Mary into coming into her own. Unfortunately, all this occurs in the last ten minutes of the film. For whatever reason, Mary is most definitely a sidelined supporting character, whose potential is never fully realized in the cinematic release, as director’s commentary and the trivia about the shooting script attest.

Splice explores gendered body horror at the locus of the womb, reveling in the horror of procreation. It touches on themes of bestiality, incest, and rape. It’s also a movie about being a mom.

Though it received somewhat lackluster reviews, I encourage anyone interested in feminism and film to give Vincenzo Natali’s sci-fi body horror film a try. Splice features female characters who are intelligent, emotionally complex, and incontrol. They’re not perfect, but they are three dimensional characters whose decisions drive the story. (One of them morphs into a male, but we’ll get to that.)

Splice asks a lot of questions about the terms and conditions of conception, gestation, birth, and motherhood, all without stabbing the viewer in the eye with reductive answers.

It also features some campy moments. Hipster scientists shout things like “It was the only way!” Academy Award winning actor Adrien Brody expresses his frustration by throwing down not just his jacket, but his scarf as well!

If you can stomach the juxtaposition of big thinky concepts and stilted clichéd dialogue, you will find Splice a thoroughly enjoyable mindfuck of a film.

There are moral issues at stake throughout the entire series, including the erosion of prisoners’ and laborers’ rights so that others may live more comfortably. The same critical lens is cast on forced birth, forced abortion, eugenics and abortion restrictions.

Early in the second season, Kara “Starbuck” Thrace has returned to Cylon-occupied Caprica (home planet for the crew of Battlestar Galactica) to find her destiny and aid the resistance, a group of humans who have stayed behind to fight the Cylons. She is kidnapped and knocked out, and wakes up in a hospital bed. Her “doctor” (who later is revealed as a Cylon) tells her she was shot in the abdomen and they have removed the bullet. As she drifts in and out of consciousness, she becomes suspicious. The doctor has excuses for every inconsistency. He tells her they’d operated because they suspected she had a cyst on her ovary. He says, “You gotta keep that reproductive system in great shape… it’s your most valuable asset these days. Finding healthy childbearing women your age is a top priority for the resistance. You are a very precious commodity to us.”

Starbuck replies, “I am not a commodity. I’m a viper pilot.”

To me a character that deserves the reputation of a feminist heroine would be Carolyn Fry(Radha Mitchell) from David Twohy’s Pitch Black (2000), regardless of whether he intended it that way. We have time to watch her character grow through the movie, but she is a secondary character, Riddick is the famed anti-hero. To make an impression in spite of that is huge.

While Fry takes the reins of the group on the deserted planet by default, the one thing that drives her bravery is her terrible mistake — attempting to eject the passengers in cryogenic sleep to lighten the load of the spaceship before it crashed, stopped from doing so by the more conscientious navigator who died as a result, earning her a lot of resentment from the group, their mistrust eventually pushing her to fight for her leadership position more fiercely. I don’t particularly consider that a negative point, I see a person deeply ridden with guilt, antagonists willing her to fail, Riddick keenly watching her every move, reacting to her willingness to risk her safety for the sake of the others with amusement. I see a lot of a pressure on a person who is not particularly skilled to handle the task before her, but she pushes on in spite of that.

Mastermind behind phenomenal, groundbreaking television hits, Buffy The Vampire Slayer and Angel and recently helming a little box office smash called The Avengers, Whedon has always crafted the powerful, intelligent female hero. He illustrates that aesthetic further in the short lived FOX series Firefly turned feature motion picture, Serenity showcasing not just one, but four intriguing women characters- Zoe, Kaylee, Inara, and River.

In a science fiction space western combining a thrilling taste of adventure, mayhem, and Whedon’s trademark humor, flying aboard with the wisecracking Captain Malcolm Reynolds, softhearted Wash, short-tempered Jayne, and the good doctor, Simon, these spirited and diverse women bring more than male gazing eye candy ornamentation.

Science fiction is, or should be, a place to examine stereotypes and political and social conventions, not to reinforce them. Before Le Guin came along, we had authors like Piers Anthony (a notorious misogynist, although like most misogynists he denies that he is one) and Ray Bradbury. Now I wouldn’t go so far as to call Bradbury a misogynist — I admire Bradbury’s work, I really do, because many of his themes are universal. But he falls into the same trap that Stephen King does — very few of his main characters are female, and more often than not, men are the decision makers, and the ones that move the plot along. It’s interesting to note that many writers tend to write towards their own gender. In Bradbury’s fiction, like Anthony and King, the female characters often end up in supporting roles as wives, mothers, and crushes that turn into ‘marionettes’ or a controllable programmable robot that can be easily manipulated.

I read these books as a child and teenager, and I experienced a sense of dissatisfaction with the minor roles women were playing in this male literary playground. So I wondered what women writing science fiction would be like, and that’s where I found Ursula Le Guin, who didn’t merit her own displays in the library lobby like the other authors I’ve mentioned. At least, not when I was a kid.

WALL-E, it seems, has developed human qualities on his own. He is also capable of keeping up with a robot approximately 700 years newer (read: younger) than he is–an impressive age gap in any relationship. EVE worries over WALL-E and caters to his physical limitations (he is, after all, an old man–with childlike curiosity), acting as nursemaid in addition to all-around badass. Who says we can’t be everything, ladies? While EVE doesn’t have any of the conventional trappings of femininity, she’s a lovely modern contraption with clean lines, while WALL-E is clunky, schlubby, and falling apart (not to mention he’s a clean rip-off of Short Circuit‘s Johnny 5)–reinforcing the (male) appreciation of a certain kind of female aesthetic, while reminding girls that they should look good and not worry too much about the appearance of their male love-interest.

And while some of the scenes are admittedly, far more graphic and gratuitous than I think necessary (there is a simple purity to the original Alien death scenes that I think is lacking here), the film featured some thought provoking and disturbing themes, though all backed again by a strong, smart, female scientist-turned-reluctant heroine and survivor, similar to the original Ripley.

The Swedish Noomi Rapace (seriously loving these Swedish actors) and South African Charlize Theron oppose each other brilliantly; Theron as the efficient and disdainful corporate heavy, Noomi as the resistant, believing, courageous scientist out to find some answers.

The film features a hefty score of themes for discussion, including one of the most disturbing abortion scenes I’ve ever seen. That scene is apparently what pushed the film up from a PG-13 rating into an R; if the studio had wanted to ensure a PG-13 rating, the MPAA demanded that they cut the entire scene. However, both director Ridley Scott and Rapace felt the scene was pivotal in Shaw’s intense desire to survive and in her emotional and mental development. If you weren’t pro-choice before, chances are you might be after witnessing this scene.

As I watched Avatar, I for some reason (probably because predicting the next thing that would happen got boring once I realized I would never, ever be wrong) began thinking about the first time I saw 2001: A Space Odyssey and asked myself how the genre of science fiction and the movie industry as a pillar of American culture had changed in the time that had elapsed between the two films. What were the general cultural values and concerns being communicated in each of these films? What kinds of stories were being told about the world? How had cinema as a means of artistic communication and social commentary changed since 2001 was released? What do the methods of presentation in both films tell us about the ways in which our society has changed in the era of advanced mass communication? And, of course, how was gender represented?

I came to a few distressing conclusions. Naturally, I’ll get to the feminist criticism first. By the time Avatar came out, we’d traversed 41 years in which women’s status in society had purportedly been progressively improving since 2001 was released, but the change in representations of women in popular media, at least in epic sci-fi movies, doesn’t look all that positive. In 1968, we (or Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke) could imagine tourism in space. We could not, however, imagine women occupying any role in space exploration other than as flight attendants. In 2009 we (or James Cameron) could imagine female scientists and helicopter pilots participating in extraterrestrial imperialism, and we could even tolerate warrior-like blue female humanoid aliens as central figures in the plot of an movie, but we still couldn’t imagine a world in which traditional gender roles and current human beauty ideals aren’t upheld, even when that world is literally several light years and 155 years away from our own.

So it might be easy to dismiss Jo as one of those useless female companions. A pretty bit of skirt to be an audience stand-in for the Doctor to explicate to. Except for the fact that Jo Grant is awesome. She’s a trained escapologist, she can fly a helicopter, she can abseil; in ‘The Mind of Evil’, she karates a prison riot leader out of his gun. On numerous occasions, when the Doctor’s got himself locked up somewhere, she comes to his rescue. Though in her first appearance, the Master hypnotises her, the Doctor teaches her how to resist it, so that in later confrontations, the Master is utterly frustrated by his inability to dominate her mind. In ‘The Time Monster’, when they run into the Master, again, and he finds himself unable to find anything to say, she mockingly suggests, ‘How about, “Curses, foiled again”?’ She’s also bold, capable of making hard decisions under pressure. Again in ‘Time Monster’, the Doctor threatens their mutual destruction by initiating a Time Ram, shoving his and the Master’s TARDISes into the same temporospatial coordinates; but when the Doctor hesitates, Jo’s the one who makes the final move to press the big red button.

District 9 operates with what I’d call an absent feminism, which isn’t quite an anti-feminism but a disregard for a female world altogether—except when a minor feminine presence functions as off-stage impetus for the lead character. Aside from a few bit parts, the most prominent female role is that of Wikus’s wife, Tania (Vanessa Haywood), who, although rarely seen onscreen, becomes the driving motivation for Wikus to risk his life to find the cure for his “prawnness,” befriending, out of necessity, Christopher Johnson, the same alien he tried to evict earlier in the day. (Wikus didn’t know then that Johnson actually built his shack atop the Mothership’s missing module; he’s been diligently working for twenty years to fix it, and was nearly finished when pesky Wikus confiscated that black fluid.)

Wikus’s wife, who is given no real identity, save the fact that she is torn between the age-old allegiance to her father and loyalty to her husband (implying that she most certainly “belongs” to one or the other), won’t relinquish hope of her husband’s return by the film’s conclusion. Someone is leaving strange gifts on her doorstep, gifts oddly similar to the ones dear hubby Wikus used to give her. Blomkamp insinuates that she’s a steadfast wife who will do her wifely duty and wait faithfully for her disappeared husband. The viewer is given no back-story or insights into their relationship; yet, forced upon us is the heavy-handed notion that they really do love each other—like, in that super-deep, eternal-love kind of way. Their story, of course, is a bottom-tiered thread in the narrative.

Only after witnessing a mother’s love does Klaatu feel that there is another side to humans (besides their unreasonable and destructive one), and curtail the attack of the killer nanobots. Unwittingly then, Benson changes Klaatu’s mind based on the advice Barnhardt gave her as they fled his house: “Change his mind not with reason, but with yourself.” In your standard anti-feminist fare, Barnhardt’s advice can only mean one of two things. Being a family-friendly film, the remake of Day passes on Benson’s seduction of Klaatu, deciding instead to confirm that she is a mother first and foremost, her position as scientist at a prestigious American university be damned.

As kickass as she is, Sarah possesses no other identity beyond motherhood. She exists solely to protect her John from assassination or humanity will be wiped out. Every decision, every choice she makes, is to protect her son. In Sarah Connor Chronicles, Cameron tells Sarah that “Without John, your life has no purpose.” Sarah tells her ex-fiancé that she’s not trying to change her fate but change John’s. Even before she becomes a mother in Terminator, her identity is tied to her uterus and her capacity for motherhood.

[…]

On the surface, it seems like the Terminator franchise revolves around a dude often searching for a father figure rather than appreciating his mother. And problematic depictions of motherhood do emerge. But who’s really the hero? Is it the smart hacker son destined to be a leader? Is it the cyborg that learns humanity? Or is it the brave and fierce single mother who sacrifices everything to protect humanity and doesn’t wait for destiny to unfold but takes matters into her own hands?

Even though Leia has romantic feelings for Han Solo in The Empire Strikes Back, she continues to call out his arrogant bullshit. She quips snappy retorts such as, “I’d just as soon kiss a Wookie” and “I don’t know where you get your delusions, laser brain.” She’s never at a loss for words and never afraid to express herself.

She also has burgeoning psychic powers as she picks up on Luke’s cries for help at the end of the film. Obi-Wan tells Yoda when Luke Skywalker leaves Dagobah, “That boy is our last hope.” But Yoda wisely tells him, “No, there is another,” cryptically referring to Luke’s twin sister Leia.

In Return of the Jedi, Leia puts herself in harm’s way posing as a bounty hunter to save Han. Sadly, after she’s captured by Jabba the Hut, she’s notoriously objectified and reduced to a sex object in the iconic metal bikini, essentially glamorizing and eroticizing slavery. And of course she needs to be rescued. Again.