|

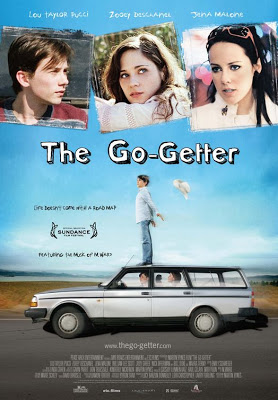

| The Go-Getter movie poster |

This is a guest post by Melanie Killingsworth.

The Go-Getter doesn’t scream “feminist.” The central character is a guy named Mercer; in fact, the movie doesn’t actually pass the Bechdel test, because no one really talks to anyone besides Mercer.

Mercer’s first words – to himself and the audience at large – are about Huckleberry Finn, not remotely feminist literature. After a little soliloquy, Mercer steals a car and starts a road trip in search of his older half-brother, Arlen. Along the way, the imagination interludes and fantastical sequences give the movie a dreamy, slightly drugged quality. Where am I going with this, and how is The Go-Getter feminist? Perhaps I should sum up the plot first.

Mercer stops at a pottery collective where Arlen used to live, only to get punched in the mouth by someone Arlen stole from. The puncher repents and offers Mercer some pot, which Mercer tries for the first time. All the collective members sit down for dinner with Mercer, and a few details about his mother come out. She was a substitute teacher and mom at 45, and though those things are hardly for the faint of heart, Mercer feels a need to portray her as a sled dog racer and later someone who travelled the Australian outback. The conversation and the pot help Mercer air some of his feelings, but he’s not much closer to finding Arlen.

The collective a bust, Mercer goes to find his middle-school crush, Joely, whom he obviously idolized; the camera angles point up at her and down at him while she climbs onto the pedestal of bleachers. Joely joins the road trip for kicks in the hopes of taking Mercer’s virginity, while Mercer dresses up and takes ecstasy to impress her before they have sex. In the end, she’s underwhelmed, and he’s apologetic.

|

| Joely in The Go-Getter |

Mercer goes from his first sexual experience to the set (shack, really) of a pornographic film where Arlen fleetingly “worked.” The director claims he’s “making art” about “making love,” but the boys in the waiting room talk about girls in dehumanizing ways, and one of the actresses dissolves into tears in the background. “What good is it if she cries before she gets fucked?” the director asks. Mercer isn’t at all sure how to respond, so he steals the camera and runs. They can’t film without it, he figures.

Mercer goes back to find Joely in the hotel with her cousin and a friend. When Mercer tries to take off by himself, the threesome steals Kate’s car and leaves. Mercer hitches a ride after them and steals the car back, again. Next stop is the pet store where Arlen ran a check-scam with an older woman. Said woman ponders Mercer, decides to take a maternal attitude, rambles a bit about free love and choice, then charms Mercer into singing hymns with her not-a-band to fulfill her community service requirements.

All this time, Mercer has been chatting with Kate, the girl from whom he stole the car. One of my favorite sequences is when Mercer is on the phone trying to imagine what Kate might look like, and the visualization runs through several women. It shows only their faces, not their bodies, and some of the suggested mental connections – the oldest of the group liking beer, one of the younger ones coming up on the suggestion of fake teeth – eschew stereotypes.

As Mercer parts ways with the pet shop woman, Kate finally shows up, more angry that Mercer lied than the fact that he still has her car. “Doesn’t anybody know anybody at all?” she asks. The two of them talk as they drive, getting closer emotionally and physically. Eventually, Mercer catches up to Arlen and gets scorn and a bloody lip for his trouble. Kate comforts him, and later they have sex.

|

| Kate as both nurturer and protector |

Mercer is finally able to sit down civilly with Arlen. Mercer is not crushed by Arlen’s anger; he addresses Arlen as an equal. No begging, no insecurity or needing a big brother’s acceptance. All the things Mercer has learned about women along the way led Mercer to his brother. Sex may be the turning point that leads to this conversation, but it’s the conversation that causes Mercer to realize he has “become a man,” and a man mostly shaped by women, at that.

So what makes a man’s coming-of-age story a “feminist” travel film? The fact equal-opportunity is still so rare these days? No, (though on a side note: sadness and anger!). It’s because as Mercer’s trip progresses, the catalysts are fully-realized women who exist for more than just his gratification. His trip is prompted by his mother’s death. All his stops along the way involve women who reveal something about themselves and/or Mercer. Finally, Kate, from whom Mercer stole the car, tracks him down and finishes the road trip with him. In a moment near the end, Mercer asks Kate, “Want to go to Louisiana with me?” and she raises her eyebrows and notes, “It’s my car,” as if to sum up that though Mercer has been making his own way, it’s women who are enabling and teaching him. It’s women he has learned to be like or not-like, from his mom to his first crush to this girl he just met over the phone.

|

| Mercer talking to Kate on the phone, while imagining her as his shoulder angel |

Women are sexual beings who initiate all Mercer’s intimate interludes. Women make small talk about weather and geography and deep conversation weighing fate versus coincidence. Women are nurturing (they cook food and tend to Mercer’s various injuries), but also capable (they make pottery, paint doors, and run stores). Mercer – and at times other men – are also portrayed as nurturing and loving, and none of these are seen as undesirable or distinctly “female” qualities.

A potential negative to the feminist theme is the porn shack scene. Coming-of-age must deal with sex, but since Mercer deals with it in other ways, is this underdeveloped side trip necessary? It has at least one damsel in distress, one predatory director, and three young boys who are likely being taken advantage of by the director, but who are also looking at the experience as their license to take advantage of the girls. Mercer weakly condemns it, then runs from it. The only real reason for its inclusion is – in leading to Mercer stealing the camera – girls again become a catalyst and point out the uncertainty in Mercer’s actions. He won’t be confident in his decisions until the end of the film when he reaches “manhood.” Of course, it also gives Mercer another noble reason to steal a prop useful to the story, so one could argue for pragmatism.

Another possible negative, Joely’s sexual manipulation of various men, is seen as an individual choice. Her “sins” aren’t sex or promiscuity or drugs; they’re theft of things Mercer already stole. She’s only his equal there, and none of her choices are representative of womanhood, just as Mercer’s choices aren’t representative of manhood.

Neither of these quibbles takes away from the overall woman-positive tone of the story. Kate responds to Mercer stealing her car with frustrated intrigue and working things out verbally. In opposition to this method, violence, the “male” answer to problems (as in, here always perpetrated by males), happens four times – the potter lashing out at Mercer because of Arlen; the three friends physically assaulting Mercer to steal Kate’s car; Mercer attempting to steal the car back, being mocked until someone discharges a gun; and finally, after years of repressed emotion, when Arlen demeans their mother and he and Mercer exchange blows. “Get yourself a hunting knife, can’t nobody take your hat,” the liquor salesman advises.

|

| Mercer’s fantasies imagine how the violent road taken would end |

Instead, Mercer becomes strong without violence, has sex without unrealistic idealizations, comes to terms with his brother, and realizes much about himself. All this he learns from women, while he and the story embrace and accept women as equal, strong, complex creatures with agency. Add to that a car trek cross-country to Louisiana – voila! – feminist travel film.

A film doesn’t have to have a woman as the main character to be feminist. This story unabashedly demonstrates the importance of women, not just in relation to men, but to themselves and the world in general.

Melanie Killingsworth is a writer and filmmaker in Portland, OR. Her feminist noir The Lilith Necklace is currently applying to a film festival near you.