“The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” – William Faulkner

Written by Leigh Kolb

Spoilers ahead

In 2011, two presidential hopefuls

signed a pledge that, in its original form, insinuated that African-American children had families that were more cohesive and better off during slavery.

Texas and Tennessee both in the last two years have seen school boards and political activist groups push K-12 curriculum that

“softens” slavery references, explores the “

positive aspects of American slavery” and downplays minority struggles throughout American history.

A southern governor

issued a proclamation for Confederate History Month with no references to slavery in 2010.

Quentin Tarantino’s

Django Unchained, an anti-slavery revenge fantasy (based more in fact than fiction) was released just a few days before the 150th anniversary of the

Emancipation Proclamation, which was passed on Jan. 1, 1863 (however, it would be almost three more years until slavery was outlawed in the United States with the Thirteenth Amendment).

If you find the above information upsetting–that many are trying to whitewash a history so fresh and raw (after all, 150 years is not that long ago)–then Django Unchained is for you. If you don’t find the above information jarring, then perhaps the film is especially for you.

Tarantino has been candid in many interviews about his desire to showcase this time in American history (the film is set in 1858, two years before the start of the Civil War). His 2009 film Inglourious Basterds was a Holocaust revenge fantasy–not historically accurate, but emotionally fulfilling. Django Unchained‘s fiction isn’t as factually inaccurate, but the cathartic nature of looking at a historical horror through the lens of revenge is still there.

Tarantino recently explained this catharsis on

NPR:

“… to actually take an action story and put it in that kind of backdrop where slavery or the pain of World War II is the backdrop of an exciting adventure story — that can be something else. And then in my adventure story, I can have the people who are historically portrayed as the victims be the victors and the avengers.”

He goes on:

“You know, there’s not this big demand for, you know, movies that deal with the darkest part of America’s history, and the part that we’re still paying for to this day. They’re scared of how white audiences are going to feel about it; they’re scared about how black audiences are going to feel about it.”

This fear is certainly understandable, since America’s history of slavery, racism and subjugation is still, in many ways, a taboo topic (or a topic rife with revisionism). Django Unchained, however, does everything right.

The opening scene of the film is a line of raw, whipped black backs. This image is not foreign to audiences–people are generally well-versed in that aspect of violence against slaves. The image is awful and uncomfortable, but eases the audience in to this time period with something familiar. As the film progresses, layers of violence and misery are peeled back until audiences are squirming and uncomfortable. As they should be.

For the first part of the film, Dr. King Schultz (Christoph Waltz) and Django (Jamie Foxx) are portrayed as partners. Both have stories, and basically split the role of protagonist. Schultz frees Django to aid in his bounty hunting. In their time together, Schultz teaches Django to read, shoot and “act” however he needed to in order to accomplish his goals.

|

| Schultz teaches Django how to shoot and read, granting him access to the free world. |

The poignant scenes where Schultz and Django are eating together in their camp highlight the importance of authentic voices. They ask one other questions and learn one another’s stories. Schultz acts shocked when he learns that Django’s wife, Broomhilda (Kerry Washington), speaks German. He was intrigued by their story, and asked Django about her and their life together.

The importance of the authentic voice and hearing people tell their own stories is essential. How, then, can Tarantino, a white man in 2012, effectively bring the injustice of slavery to mass audiences?

The answer can really be found in the film itself.

Schultz tells Django the legend of Brünnhilda (which mirrors Django’s own journey for his wife). Django asks Schultz why he is helping him, and why he cares whether he finds his wife, and Schultz answers, “I’ve never given anybody their freedom before. I feel responsible for you.”

This responsibility to give Django access to the free world is similar to Tarantino’s responsibility to bring this black empowerment film to mass audiences. It’s about access, not help or hand outs. Access is what white Americans (especially white American males) still have at this point, and they should be responsible for sharing that access with others and telling important stories. Tarantino’s popularity and neutrality (as a white man with no other “agenda”) gave access to this story.

Could a

black man have made a film with a celebrated hero who says, “Kill white people and get paid for it? What’s not to like?” I can’t imagine that would have had the same

mass appeal. While I’m not suggesting that this is a fair or good scenario, that’s where we are in our history. And if we’re going to continue to have people downplaying our nation’s history of oppression and “softening” slavery, we

need these stories more than ever.

As this access is granted to Django, the story becomes more and more his own. He changes after the first bounty kill. Two men are getting ready to whip an enslaved woman; Django shoots the one who is quoting Bible passages and holding the Bible (he shoots him through a Bible page that is stapled to his shirt) and whips the other. He has claimed his place, and his journey begins to be more wholly his own. (The shot to the Bible page is also important considering pro-slavery factions would use the Bible as a defense for owning slaves.)

|

| Django turns the whip on the oppressor. |

By the time the two reach Candyland, Django has truly come into his own. As they travel across the horizon, rapper Rick Ross’s

“100 Black Coffins” plays as Django struts on his horse (Foxx was instrumental in

helping choose this music). The rap

works, and indicates a shift in whose story we’re really starting to see. When Schultz warns Django to stop “antagonizing” plantation owner Calvin Candie (Leonardo DiCaprio), Django asserts that he’s just “getting dirty,” and acting like he knows he needs to. This dialogue upends the “know your place” rhetoric that even well-meaning, slavery-hating Schultz falls into.

The use of mandingo fighting as a plot point (both to get Schultz and Django to Candyland, and also to horrify the audience) is important. While forcing slaves to fight or entertain for sport and profit was not uncommon, this kind of fighting until death

didn’t appear to happen. And before you take a big sigh of relief (it wasn’t

that bad, then), the main reason this kind of fighting would not have happened is because it was

economically unwise to kill someone who would be a strong worker. It’s all business.

Candie’s continued references to phrenology remind us that in addition to the perceived Biblical support of slavery, pseudoscience of the time also supported racist (and sexist) ideas about people’s capabilities.

When he breaks apart old Ben’s skull at the dining room table, one can’t help but think about poor Yorick in

Hamlet. As Hamlet cradles the skull of his father’s jester who he knew well as a child (much like Ben’s role as Candie’s father’s slave), he considers life and death and reflects upon how we all end up the same. Ben’s skull, however, launches Candie into a tirade about phrenology, as he breaks a piece off to show the indentions that prove black people are biologically subservient.

|

| House slave Stephen, left, Broomhilda and Candie. |

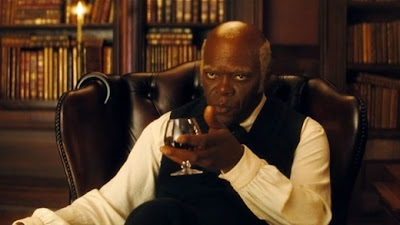

Behind Candie always in these dining room scenes is a marble statue of two Roman gladiators fighting (his hobby is nothing new), and is Stephen (Samuel L. Jackson), his house slave. Stephen embodies the Stockholm Syndrome kind of subservience that Candie sees as inherent. He plays the ultimate “Uncle Tom” character to foil Django’s free and increasingly independent and violent nature. Of course, in keeping with the Ben/Yorick parallel, Stephen also is much more clever than Candie is, and has wisdom and knowledge (Shakespeare often gave the jesters/fools much more wisdom than their masters).

|

| Stephen. |

The way Candie and Stephen treat Broomhilda is abhorrent, and Django predicted correctly that she was used as a “comfort girl” (sex slave). While her part is the damsel in distress, she’s clearly as fierce and independent as she can be (when they arrive at Candyland, she’s being brutally punished for trying to escape).

As business is being settled toward the end, Schultz cannot stop the images of a dog killing a runaway slave they’d encountered earlier. He’s not angered by losing a much larger amount of money than he’d anticipated, or being “caught” in a scheme. He’s haunted by the brutality he’s seen at Candyland. He starts discussing The Three Musketeers with Candie, and tells him that Alexandre Dumas was black (again reinforcing the idea that it is important to have the whole story to avoid reducing people to stereotypes). A demand for a handshake becomes too much for Schultz, and he shoots Candie, setting off a bloodbath. He knows he’s sacrificing himself with that gesture, but it’s worth it to him.

Few remain alive after the resulting gunfight, but Django and Broomhilda are both caught and punished. Django, in the throes of torture and seconds away from castration, is visited by Stephen, who rattles off all the ways they could have punished him, but Candie’s sister ordered that he be shipped to a quarry, where he’d be enslaved again.

“This will be the story of you, Django,” says Stephen.

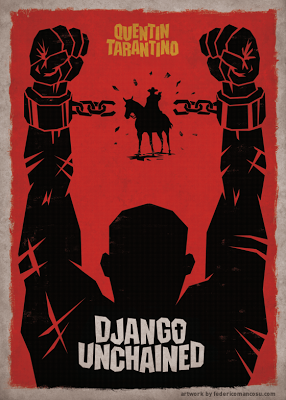

While Django’s story began by being freed by Schultz and partnering with him, thus receiving access to the free world, he long ago became the author of his own story. And Stephen’s wrong–Django wins. Django frees himself this time.

As Django kills Stephen, Stephen screams, “You can’t destroy Candyland–there’ll always be a Candyland!”

And while Django does effectively end Candyland, Stephen isn’t incorrect. Candylands will exist for years after Django leaves, and we are still feeling what Candyland was in America today.

In an

interview with VIBE, DiCaprio, Washington and Foxx discussed their reactions to the screenplay. DiCaprio said,

“For me, the initial thing obviously was playing someone so disreputable and horrible whose ideas I obviously couldn’t connect with on any level. I remember our first read through, and some of my questions were about the amount of violence, the amount of racism, the explicit use of certain language. It was hard for me to wrap my head around it. My initial response was, ‘Do we need to go this far?'”

Foxx and Washington said,

Foxx: “When President Obama became president in 2008, a blemish on my hometown was the fact that it wasn’t on the front page of the newspaper. When they went down to talk to them, they went [country accent] ‘Hey listen, we run a newspaper, not a scrap book.’ I’m paraphrasing. So I had both of my daughters come down to the plantation, and I walked them through and I said, ‘This is where your people come from. This is your background.’ And I said, ‘this is more than just a movie for your father.’ My little daughter, I took her into the shack, and I said, ‘these are where the slaves stayed.’ Every two, three years there is a movie about the holocaust because they want you to remember and they want you to be reminded of what it was. When was the last time you seen a movie about slavery?”

Washington: “When is the last time you saw a movie about slavery where a black man frees himself?”

Foxx: “We read back in the day about Nat Turner and other guys who were not taking it. That’s why, when I read the script and we went back to the plantation, there were certain things inside me bubbling up.”

These responses are indicative of the conversations about our own history. White people frequently echo variations on a theme of “I didn’t have anything to do with that.” It’s easy to denigrate and forget a past that we keep ourselves disconnected from. For black Americans, however, there is a sense of connectivity, of history, to that time and place. As there should be–for everyone, no matter how painful it is.

|

| Django leaves a pile of bodies in his trail to freedom. |

Django Unchained is an excellent film. The writing, direction, acting and soundtrack are powerful. And while it’s poised to be at the receiving end of many accolades this awards season, the best, most lasting impression it can leave is to change conversations and common narratives (even fictional ones) so that whitewashing our history becomes impossible.

—

Leigh Kolb is a composition, literature and journalism instructor at a community college in rural Missouri.