|

| Best Picture nominee Michael Clayton |

Tag: Mystery

Guest Writer Wednesday: Incendies

Incendies: Lebanon Is Scorched, Burned and Blistered

|

| A cinematic moment. The image comes first and the explanation comes much much later. |

|

| Violence and pain become sources of empathy and identification for the audience. |

|

| The now classic diasporic subject returning to the ‘homeland’ and looking. |

|

| The protagonist is played by Lubna Azabal, a Moroccan actress who is a contender to be the next generation Hiam Abbas. Hiam Abbas is the Arab world’s Meryl Streep. |

Movie Review: Source Code

|

| Original artwork by Markgraf |

The last film I reviewed, Sucker Punch, had a magnificent trailer. It really stoked me. I was all, “Hey, this trailer is awesome! I must avail my face of the cinematographical delight it advertises!” And then I saw it and it was crap.

But I went to see it anyway, because my passion for Jake Gyllenhaal’s beautiful face is unrivalled and disturbing. And also because Duncan Jones’s breakout film, Moon, was widely touted as a dreadfully disturbing psychological affair, and I still rue the fact that I missed it at the cinema – so maybe it would have my proverbial cookies after all?

Short answer: yes.

Long intelligible answer: It certainly does. It turns out that the film’s content is the complete opposite of what the trailer would have me believe. The trailer bigs up the romantic relationship and downplays the unsettling premise. The film, on the other hand, is all about the premise, which rules the shop from start to finish, throwing up questions of morality and ethics in science, what happens to the universe when we make decisions, and the nature of a good death. The romance is a barely-there breath of something sweet and touching that’s symptomatic of the premise rather than an event all in itself.

The premise, without spoiling anything, is that there is some military science (SCIENCE! more like) that allows a person to take possession of a dead person’s final memories, ten minutes before their death. This involves, of course, a poor bastard (in this case, a harassed-looking, sweaty Jake Gyllenhaal) being held prisoner in a Science Tank and forced back into some dead guy’s brain so that he can solve terrorism forever. In this case, Jake Gyllenhaal scuba dives through time and space into ten minutes prior to a big-ass explosion that detonates an entire train on the way to Chicago.

So the reason, then, that there’s this romantic subplot anything, is less about OH ROMANCE, SAVE THE LADY, THE MERE PRESENCE OF A WOMANLASS MAKES MAN LOSE ALL SEMBLENCE OF RATIONALITY AND FLING ASIDE ALL PLANS AND SCHEMES FOR HER, FOR SHE IS RUBBISH GIRL! WHO CANNOT SAVE HERSELF! AND HE IS ERECTILE-TISSUE-BRAIN MAN! WHO THINKS OF NOTHING BUT WHETHER OR NOT HE CAN BESHAGGERATE A THING! and more about giving this woman – and her fellow passengers – a chance to have a good death.

Another thing: although this film deals heavily with military science – a combination of fields that stereotypically leaves women out wholesale – one of the lynchpin characters is a woman, and she’s not only steely and full of agency and poise, but she carries a bucketload of morality and cunning, too. I loved her. I was very glad she was in it to balance out the do-stuff-and-explode machismo of Jake Gyllenhaal Fighting Science.

Overall, yeah! Source Code is surprising: it’s a fun and entertaining ride without being brainless. Also, I did mention the thing with Jake Gyllenhaal and he’s in a suit and he’s doing things and oh god help I’m on fire.

YOU SHOULD SEE THIS FILM BECAUSE:

- It’s not revolve-around-romance stupid as the trailer makes it out to be

- It does fun and interesting – if not necessarily innovative – things with choice-making and time

- Morals and ethics and science, oh my

- Jake Gyllenhaal, suit, things, oh god his gorgeous face etc.

- Some bits are, if you think about them, really fucking creepy

YOU SHOULD NOT SEE THIS FILM BECAUSE:

- Well, the science is fucking hilarious. Wait, that’s a reason to see it.

Markgraf draws pictures, plays Pokemon, watches films, writes for BadRep, caresses tanks, talks to himself in public and collects interesting bits of cardboard. He wishes he had a life.

The Flick Off: Bored to Death

|

| The first season of HBO’s Bored to Death |

Honestly, the last thing we really need is another show about white male hipsterism. Set in Brooklyn? Check. Protagonist is a whiny artist type? Check. Whiny artist-type best friend? Check. Kooky outsider friend? Check. Bromance-style hijinks? Check. One-dimensional women? Check. Women who inhibit the protagonist and his best friend? Check. Money not an issue? Check. You get the picture, right?

Don’t get me wrong: Ted Danson is very funny in this show, even if he is just playing a less-evil Arthur Frobisher (from the fantastic Damages), replacing coke-fueled corporate crime with pot-fueled magazine-editor slickness and humor. That’s about the only compliment I can give this snooze-fest.

The premise of Bored to Death is a bit weak, yet has potential: With nothing else to do besides write his second novel, character Jonathan Ames (named by real-life writer Jonathan Ames, played by Jason Schwartzman) offers himself for hire on Craigslist as an unlicensed investigator. Jonathan only drinks white wine now since his girlfriend henpecked him about drinking, he’s really sensitive, and, come on, he’s a lovable hipster. FEEL SORRY FOR HIM! The fact that his cases are small and insignificant (the case of the stolen skateboard, finding a woman whose workplace and stage name are already known) isn’t the problem; the problem is that they mean nothing. Jonathan is such a boring person that he investigates other people’s problems to mine them for story ideas, since, you know, he’s blocked and his second book is due. At least I think that’s why he’s doing it. Also, it’s a semi-interesting way to procrastinate (it could be a hilarious way to procrastinate, but the show rarely, if ever, reaches those heights). Another HBO show, which shares the premise of an unlicensed detective investigating often small crimes, The No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency, has purpose and smarts. This unlicensed detective show is all about the ego of Jonathan Ames.

Here’s the real reason for the flick off: the women are awful. They aren’t bad people—we’re not dealing with the galling misogyny of Hollywood blockbusters here—but they’re so lazily written that I can’t believe HBO, usually so keen on characters, greenlit this show. Bored isn’t interested in who its female characters really are, as its main characters aren’t interested in anything but their own egos. Ray (Galifianakis) complains about his girlfriend’s obsession with their lack of intimacy, and she regularly suggests ridiculous solutions, including Ray getting a colonic, Ray going to therapy, and Ray giving her timed massages—yet she still gives him “an allowance” so he has money for essentials like weed. Jonathan’s ex-girlfriend, whom he is still obsessed with, seems to exist only to walk her little white dog while wearing gorgeous lady-hipster outfits and torture him with her beauty of lack of love for him. Guest stints from very funny actresses—including Parker Posey, Kristin Wiig, Jenny Slate, and Bebe Neuwirth as Jonathan’s editor–are utterly wasted. (As is Zach Galifianakis, actually.) These women aren’t there to be funny, or, you know, be people; they appear mostly as male fantasies (smart, beautiful women who would have anything to do with Jonathan and Ray) and nightmares (underage, duplicitous, blackmailing, domineering, hysterical, criminal, etc.)

Every time an interesting concept comes up, the show detours so as to not actually have to deal with said interesting concept. A character doing this would be fine and fitting; the show doing it tells me that the writer (ahem, Ames) is too close to the characters and show. For example, Ray agrees to donate his sperm to a lesbian couple, only to learn that the couple gave him fake names and sold his sperm to twenty-one other couples. This is a funny set up (if you can get past the evil lesbian trope)! So, Jonathan and Ray totally investigate the case, figure out who these women are, and run into all sorts of funny trouble on the way, RIGHT? Um, no. They happen upon a list of women who bought the sperm, and visit these women to see if any are pregnant. One is. Ray is happy? What? Huh? End of episode. What? Yeah, that’s about it.

You might wonder why I even watched the show, knowing it centered on privileged white male characters who think they are funnier and more interesting than they actually are. Good question. I guess I retain hope that such a show might be well written and funny. That maybe such a show could be a humorous examination of characters like these, instead of a blindly sympathetic ego trip. I’m open to giving a lot of things a chance, when maybe I should just skip them. I don’t want to be cynical, though, and HBO has a way of surprising us with its programming. (Take The Sopranos as an example: this show is an indictment of the American upper-middle class, disguised as a show about a mafia family. Granted, it has its own problems, but I never expected to like it as much as I did.)

Bored to Death is ready to begin its third season. Since it is still on the air, I hope it has improved from the first season I watched on DVD. I can’t say I’m optimistic, but since I don’t have premium cable, you might know better than me. So, what did you think of season one? Have you watched subsequent seasons/episodes? What do you think?

Guest Writer Wednesday: The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet’s Nest

|

|

| Enemy of the State: Heroine Lisbeth Salander Fights Back in The Girl Who Kicked The Hornet’s Nest |

This is a cross post from Opinioness of the World.

|

| Michael Nyqvist stars as Mikael Blomkvist |

In the U.S., the first book entitled The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo

In the U.S., the first book entitled The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo

|

| Annika Gianini (played by Annika Hallin) with Lisbeth Salandar (Noomi Rapace) |

She does not complain and she doesn’t accept being a victim. Almost everybody has treated her so badly and has done horrible things to her but she doesn’t accept it and won’t become the victim they have tried to force her to be. She wants to live and will never give up. I find that so liberating. Her battle is for a better life and to be free and I think everybody experiences that at some point in their life. They say OK, I’m not going to take this anymore. This is the point of no return. I’m going to stand up and say no. I’m going to be true to myself and even if you don’t like me that’s fine. I don’t want to play the game of the charming nice sexy girl anymore, I’m me. I think everybody can relate to that.

Megan Kearns is a blogger, freelance writer and activist. A feminist vegan, Megan blogs at The Opinioness of the World. She earned her B.A. in Anthropology and Sociology and a Graduate Certificate in Women and Politics and Public Policy. She lives in Boston. She has previously contributed reviews of The Kids Are All Right, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, and The Girl Who Played with Fire to Bitch Flicks.

Guest Writer Wednesday: The Girl Who Played with Fire

|

|

| Good Girl Gone Bad: Noomi Rapace as Lisbeth Salander Burns Up the Screen in The Girl Who Played with Fire |

Guest Writer Wednesday: The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo

|

| Rebel with a Cause: A Feminist Heroine Emerges in film The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo |

This is a cross post from Opinioness of the World.

The story revolves around the disappearance of Harriet Vanger, the niece of a wealthy business tycoon, who vanished without a trace 40 years earlier. Harriet’s uncle has been tortured by her absence all these years. Journalist Mikael Blomkvist, who’s been convicted of libel, and Lisbeth Salander, an introverted punk who’s a brilliant researcher and hacker, seek to solve the baffling mystery. The book is a riveting twisting thriller with numerous suspects.

Blomkvist is an interesting character. A charming and passionate journalist championing for the truth, he vacillates between cynicism and naïveté. Dejected after his conviction, he yearns to clear his name. He also frequently bed hops yet has enormous respect for women, often befriending them. While acclaimed Swedish actor Michael Nyqvist gives a valiant effort, he does not imbue the character with enough charisma.

But the sole reason to go see the movie (and read the book too) is for Lisbeth Salander. Noomi Rapace, who won a Guldbagge Award (the Swedish Oscars) for her portrayal, plays her perfectly. She stepped into the role by training for 7 months through Thai boxing and kickboxing (in the books Lisbeth boxes too) as well as piercing her eyebrow and nose, emulating Lisbeth’s punk look. A nuanced performance, Rapace plays the tattooed warrior with the right blend of sullen introvert, keen intellect and fierce survivor instincts. Salander is a ferocious feminist, crusading for women’s empowerment. Facing a tortured and troubled past, Salander is resourceful and resilient, avenging injustices following her own moral compass. An adept actor, Rapace conveys emotions through her eyes, never needing to utter a word. Yet she can also invoke Salander’s visceral rage when warranted.

Also, if you’re like me and reading each book before you see the film and you haven’t read the second book yet, be prepared for spoilers as there are scenes NOT in the first book that are taken from the second book and integrated into the film, such as Lisbeth’s flashbacks and the topic of her conversation with her mother.

In the book, Larsson makes social commentaries on fiscal corporate corruption, ethics in journalism, and the role of upbringing on criminal behavior. Larsson also provides an interesting commentary on gender roles with his two protagonists. Despite Blomkvist’s social nature and Salander’s private behavior, they both stubbornly follow their own moral code. Both also possess overt sexualities. Yet society views Blomkvist as socially acceptable and perceives Salander as an outcast. These themes are absent from the movie adaptation.

In the book, Larsson makes social commentaries on fiscal corporate corruption, ethics in journalism, and the role of upbringing on criminal behavior. Larsson also provides an interesting commentary on gender roles with his two protagonists. Despite Blomkvist’s social nature and Salander’s private behavior, they both stubbornly follow their own moral code. Both also possess overt sexualities. Yet society views Blomkvist as socially acceptable and perceives Salander as an outcast. These themes are absent from the movie adaptation.

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo has received an exorbitant amount of attention for Larsson’s controversial central theme of violence against women. It’s true that both the book and film portray graphic violence. The movie does not shy away from the uncomfortable subject matter. In the book, women fall prey to being assaulted, murdered, and violently raped. A pivotal rape scene disturbs and haunts the viewer. But sexual assault is a reality women face, albeit an ugly truth that we as a society may not want to see. Yet Larsson in the book and Oplev in the film never made me feel as if women were victimized. On the contrary, women, particularly in the form of Salander, are powerful survivors. She fights back, not merely accepting her circumstances.

As Melissa Silverstein of Women & Hollywood wrote in Forbes,

As my friend playwright Theresa Rebeck says, “The world looks at women who fight back as crazy.” We constantly see movies, TV shows and plays where men commit violence against women. That’s our norm. Here we have a woman who is saying no more and exacts revenge. Larsson is very clearly saying what we all know and believe. Lisbeth is not crazy. She is a feminist hero of our time.

Violence against women is a pervasive issue. According to the anti-sexual assault organization RAINN, “every 2 minutes in the U.S., someone is sexually assaulted; nearly half of these victims are under the age of 18, and 80 percent are under 30.” And in Sweden, the problem is just as pervasive. Larsson states that “46 percent of the women in Sweden have been subjected to violence by a man.” We must not continue to brush these crimes aside. The original Swedish title of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (both the book and the film) is Män Som Hatar Kvinnor, which translates to “Men Who Hate Women.” I’m glad that Larsson devoted his books to shedding light on misogyny in society.

A provocative and haunting film, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo is worthy of watching for Rapace’s subtle yet powerful performance. It’s rare for an audience to see a strong, self-sufficient woman on-screen. It’s even more unusual for a movie to address the stigma of sexual assault as well as the complexity of gender roles. Watch the movie and read the book. Get acquainted with Lisbeth Salander; she may be the most exhilarating, unconventional and surprising character you will ever encounter.

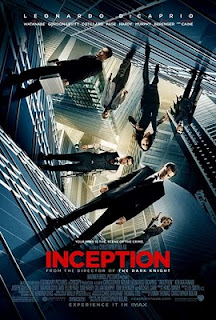

Best Picture Nominee Review Series: Inception

SPOILER ALERT

Other interesting takes on Inception:

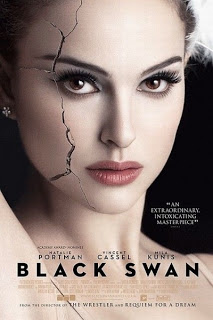

Review in Conversation: Black Swan

|

| Nina is cracking… |

Amber’s Take:

There’s a lot to say about Black Swan, and the more I think about it, the fewer definitive, and perhaps positive things I have to say. Before getting too ahead of myself, though, I must say that the performances–particularly Natalie Portman’s–were amazing, the dance sequences were compelling and seemed very well done, and the film was, overall, visually stunning. This is the most intensely visceral film I’ve seen in some time, and simply remembering certain moments still causes me to cringe. I loved the image of the goose flesh appearing on Nina Sayers’ (Portman’s) skin, as she began to physically embody her role as the Swan Queen, and the nod to Cronenberg’s The Fly when thick, black feathers began to sprout from Nina’s skin (as the hairs sprouted from Jeff Goldblum’s Seth Brundle during his physical transformation into, well, a fly).

On a literal level, the film seems to be about the transformation of an artist–in this case, a dancer–into a role. It also is, very specifically, about the physical rigor of ballet, and the lengths an artist will go to in perfecting her performance. Ballet is a physically grueling art form that seems diametrically at odds with the female body. Like gymnasts, from what I understand, a ballet dancer must fight against a mature woman’s body, maintain an impossibly thin-yet-strong physique, and endure at times severe physical pain. On a more metaphoric level, this is what society expects all women to endure, though I don’t think we can read the white swan/black swan as a direct metaphor of the virgin/whore dichotomy or expectation for women in our culture. There are several other things going on in the film, one of the most problematic being (s)mother love.

What on Earth is Barbara Hershey’s character doing in this film? In a near-deranged, over-the-top role, we see a woman who couldn’t make it out of the corps during her own ballet career, and who blames her daughter for the unhappy end to that career. Erica Sayers infantalizes her daughter, dominates her life, pummels her with guilt for under-appreciating her (the cake scene, anyone?), and generally serves as the movie’s biggest villain–worse than an artistic director who sexually assaults and torments Nina. Oh, that’s nothing compared to Mommy Dearest. So what do we make of Nina’s mother–and why was she even in this movie?

Stephanie’s Take:

While I share some of your concerns with (s)mother love, and Barbara Hershey’s character in general, I really enjoyed the film. So before I respond to some of the issues you mention, let me say what I liked so much about Black Swan:

First, a fairly obvious but no less interesting way to read the film is as an indictment of prescribed femininity. Nina’s entire existence is wrapped up in an attempt to be perfect, whether it’s striving to be the perfect ballerina or the perfect daughter. We see what her breakfast looks like, grapefruit and a hardboiled egg (if I remember correctly), and as you mention, the struggle to maintain a child’s body resonates throughout. While that may be particularly important for careers in ballet and gymnastics, it’s also our society’s ideal body type for all women, so I very much like that Black Swan delves into (however metaphorically) the potential consequences of restrictive and unattainable “perfection” in women.

When Nina can’t live up to the casting director’s Perfect Ballerina or her mother’s Perfect Daughter, she basically loses her shit. Thomas (the casting director, played by Vincent Cassel) wants her to embrace her sexuality, to seduce the audience with it (channeling the Black Swan). Erica (her mother) wants her to remain childlike and innocent (channeling the White Swan), and both Thomas and Erica represent the double-edged sword that all women face: be sexy, but not slutty; be sweet, but not a total prude. In the words of Usher, “We want a lady in the street but a freak in the bed.”)

When Nina can’t fulfill both these roles simultaneously, as much as she tries, the film shows us her breakdown: her body betrays her in literal ways, with bleeding toes and scratch marks that suggest self-mutilation (another hallmark characteristic of young women struggling to cope with similar stress); and her body betrays her in ways that suggest hallucinations: pulling “feathers” from her flesh, or ripping off her cuticles, only to discover moments later that her hand is fine. I found that part of the film, the hallucinatory transformation into the Black Swan, super interesting because it seems to happen to her accidentally—as she experiences the transformation, she doesn’t understand what’s happening, and it frightens her.

In fact, I would argue that her body isn’t her own at any time during the film. Thomas wants to control her body in a sexual way, often groping her and kissing her against her will. And when Nina attempts to explore her sexuality, to take ownership of it through masturbation, she suddenly realizes her mother is in the room (to the gasps and laughter of audiences nationwide), and she buries herself under her covers like a child. Erica constantly explores Nina’s body either by looking at her or physically touching her, often insisting that she remove her clothes—creating an inappropriateness in their relationship that I don’t quite know what to do with.

Regardless, I like that Black Swan implies that these ideals for women can’t actually exist without women destroying themselves in the process of attaining them. We live in a society where women’s bodies exist as pleasure-objects for men, as dismembered parts to sell products, as images to be dissected, airbrushed, made fun of, all under a government that continues to chip away at women’s rights to bodily autonomy. In that kind of environment, when does a woman’s body ever feel entirely her own? Black Swan sets up that metaphor quite well, asking the viewer to experience Nina’s struggle to live up to society’s ridiculous expectations for women through several cringe-worthy moments.

That rocks. But I wonder if that effort gets trumped by some of the more objectifying scenes, like the “lesbian sex scene” and the masturbation scene. Is it possible to comment on society’s expectations of women and beauty without also objectifying women in the process? Does Aronofsky linger a little too long at times? And, in response to your second paragraph, why can’t we read the Black Swan/White Swan as a direct metaphor for the virgin/whore dichotomy? (Oh, and yeah, I’ll throw it back to you—what the hell is happening with Nina and her mom?)

Amber’s Take:

You make a lovely and convincing reading of the film as an exploration of the impossibility of society’s contemporary take on womanhood. I think my resistance to this reading—or, more specifically, my dissatisfaction of this being the ultimate reading—has everything to do with Erica Sayers, though neither of us is certain how to exactly read her character. More on that in a moment (ha ha). Though meaning doesn’t end (or begin, necessarily) with a director’s intention, I also think this reading gives Aronofsky too much credit; in other words, I don’t know that the film is that good—that altrustic, that interested in women’s experience—or that cohesive.

Aronofsky has a clear interest in the limits of the human body. While watching Black Swan, I thought about his previous movie, The Wrestler, and the ways in which that solitary person pushes his body to limits most us of (those of us who aren’t professional wrestlers or ballerinas) find absurd and painful to even see. We could extend our conversation indefinitely by bringing in other movies as objects of comparison (The Red Shoes

), but I do see some structural similarities between Black Swan and The Wrestler that warrant at least a cursory comparison–and I’m sure others have done this comparative work in reviews around the web.

An important question to ask when we’re trying to figure out Black Swan is this: How do we see Nina Sayers at the end of the film? Is she a victim of her society/mother/creative director? Or is she victorious, in that she conquered the perceived limits of her body to achieve her own stated goal: to be perfect in her Swan Lake performance. (Did we see the protagonist of The Wrestler as victorious or defeated in his final leap?) Nina masters her performance, nailing the Black Swan to the point she imagines her arms transforming into wings. This was the most thrilling sequence in the film—her performance was beautiful, and much more impressive than any of the other dance sequences. Is the Black Swan a villain? In the ballet, yes, and the White Swan is the tragic heroine. Films generally tend to do a better job of making the villain more compelling than the hero, but if both roles are (metaphoric) unattainable goals, how do we read those final moments?

It’s not that I disagree with your reading—I really want that to be what the movie is ultimately about, but there are too many half-baked ideas competing with each other to allow me to say Okay, it’s about X. And, frankly, there’s an awful lot of pleasure to be had by gazing at tormented bodies in the film for me to wholly believe its feminist message. Before Nina gets the lead role in Swan Lake she looks hopefully at a woman walking toward her at a distance, and sees herself in the face of a stranger. So, she’s looking for her a reflection of herself, evidence of her own existence in other people. I don’t think this is a statement about a woman’s unstable identity; I think it’s what an artistic performer does. And possibly a person grappling with mental illness. What about Lily (Mila Kunis)? Her cheeseburger, ecstasy, and alcohol-fueled night with Nina, leading to empowered club dancing (sarcasm), random dude-kissing, and imagined sexy lesbian action between the two, does…what, exactly? Neither the skeezy artistic director’s advice (masturbate!) nor San Francisco Lily’s trite transgressions work to sexually liberate Nina…or do they? At least they bring her into active conflict with her mother.

Now. Nina lives with a mother who is basically a lunatic. I mean, let’s just say it: Nina’s mother is fucking nuts. Why (in the world of the film) does Nina need to have a mother who is fucking nuts? Couldn’t she have been moderately nuts, like most of us, with contradictions, who acts in moderately selfish ways which can moderately mess up a daughter? That would’ve allowed the themes we’ve discussed to be played out just as intricately and interestingly. How does this character fit into the movie? Taken literally, Nina’s mother is at fault for her child’s problems. As mothers tend to be in films made by men, and as psychiatrists believed in the 1960s (I’m thinking of the concept of the schizophrenogenic mother here–the idea that an oppressive mother could actually cause schizophrenia in her children). While we might be seeing a version of Erica Sayers from Nina’s untrustworthy perspective, what good is it—even if it’s not an accurate representation—for Nina to see her mother this way? Taken metaphorically…what? There’s no feminist reading I can discern in a film that I want to be feminist.

Stephanie’s Take:

I completely agree that it might not be useful, or even possible in a film as complicated as Black Swan, to come up with a definitive reading. But I still believe so much is at stake with regards to women and identity and the fluidity of that identity, in a culture that forces women to possess multiple, often contradictory identities. Maybe I’m giving Aronofsky too much credit, but I disagree with your suggestion that Nina’s literal reflections aren’t a statement about a woman’s unstable identity.

Yes, this film comments plenty on the artist and how performance can impact an artist’s life, how the artist must take on certain traits to enhance her performance, and how that act might impact her life when she isn’t on stage. However, given the fact that we’re all “performing” our identities to an extent (like the prescribed gender roles we’re taught from birth to perform), it’s worth looking at how Nina, a character whose identity seems so wrapped up in the expectations of those around her, copes—or doesn’t cope—with the pressures of womanhood and what’s required of that particular role.

It’s impossible not to notice Nina’s reflection everywhere. She sees herself reflected in mirrors as she dances, or when she’s reading the word “whore” on the bathroom mirror of the dance studio, or when she sees her face in the subway car windows. And as you mentioned, she sees her face superimposed on the faces of strangers in public—and even in the mirror at her own house, where she and Lily’s faces are superimposed.

It happens again during the sex scene; Lily’s face becomes Nina’s own face at one point, and we can hear Lily creepily whispering the words of Nina’s mother, “my sweet girl” over and over. Since we learn later that this sex scene is most likely Nina’s hallucination (and I think there’s enough evidence to even make the argument that Lily’s entire existence is a hallucination), it’s useful in interpreting the film to think about why Nina sees Lily, hears her mother’s words, and even sees her own image during a sex scene.

All this swapping of voices and faces (identities, if you will, haha) lead me to read all these people, Erica, Beth (Winona Ryder), and Lily as facets and projections of Nina’s identity. Beth, Thomas’s first “little princess,” is the aging ballerina who gets replaced by Nina, the younger ballerina. Erica, her mother, is the ballerina who slept with her director, got pregnant, and had to end her dancing career as a result. And Lily is the ballerina who embodies everything Nina tries so desperately to find within herself. She’s a carefree, sexual woman who repeatedly threatens Nina’s role in the ballet. Both when Nina is late to rehearsal and when Nina is late to the show’s opening—Lily stands in the background, threatening to take Nina’s place.

Keeping that in mind, it’s interesting that Nina “murders” Lily; on one hand, Nina seeks to absorb Lily’s empowerment, but on the other, the only way she can ultimately accomplish that is by killing it. Since murder is a pretty empowered act, I guess I get that. In fact, I think I liked it. Because Nina basically says Fuck You to the idea that Lily, who represents Nina’s unattainable sexual identity, is separate from herself, her whole self. In that moment, Nina transforms fully into The Black Swan, allowing Lily’s metaphoric death to push Nina to do what she previously thought herself incapable of accomplishing.

You argue that the alcohol-fueled, “imagined sexy lesbian action between the two” does nothing to really sexually liberate Nina. I struggled with this scene in the film probably more than any other scene because it feels exploitative and objectifying in the same way most Hollywood faux-lesbian sex scenes do. But I also believe it’s important to pay attention to all the stuff I mentioned previously. There’s tons of identity-shifting in this scene. Nina’s eventual sexual liberation (if we equate her successful transformation into the Black Swan with sexual liberation) begins here; when identities become interchangeable in this scene, we get the first images of the gooseflesh appearing on Nina’s skin. Something empowering seems to be happening. Whether it’s actual sexual liberation or the first signs of Nina embracing all these facets of herself (Beth, Erica, Lily), it complicates things. But what does it mean?

Well! I’ll go back to my original argument: Black Swan implies that these ideals for women can’t actually exist without women destroying themselves in the process of attaining them. How many identities can we effectively perform before we forget entirely who we are? Women struggle with that in a way that men never will. More often than not, it’s women who have to give up careers for children (Erica). They get pushed out of their professions when they get older (Beth). They’re expected to balance innocence with sexuality and to know when (and when not to) express them (Nina/Lily). And the attempt to balance, express, and suppress these prescribed roles often doesn’t work without having a detrimental impact on women individually and as a whole.

Interestingly, Nina and Lily both “die” in the end. So women in this film end up visibly crazy, hospitalized, or dead. In a less complex film, that would seriously piss me off. But the death and/or disappearance and/or insanity of these women make a larger point: if they’re all separate facets of Nina’s own personality and identity, which I believe they are, it’s necessary to watch each separate character struggle—it reinforces the idea that these performed identities aren’t possible without sacrificing one’s entire self.

You asked: If the Black Swan/White Swan “roles are (metaphoric) unattainable goals, how do we read those final moments?” Good question. It fascinates me most of all that Nina claims, after the White Swan’s suicide, that her performance was perfect. But, it wasn’t. She fell down in the middle of the damn ballet. To a gasping and appalled audience (not to mention, director). If her “I was perfect” claim applies only to the ballet, then she’s referring only to her performance as the Black Swan; after all, it’s the Black Swan whose dance partner whispers “wow” as she’s walking off stage; it’s the Black Swan whose audience gives her a standing ovation; it’s the Black Swan whose director beams with pride when she leaves the stage.

So yeah, I see Nina as a victim at the end of the film. Because she wasn’t perfect; she was never perfect. The conquering of her role as the Black Swan comes at a great sacrifice to her role as the White Swan (her fall during the ballet and her metaphoric death at the end of it). The two identities can’t coexist perfectly, as much as she wants them to. In the end, she still hasn’t attained the superhuman ability to perform competing identities for a critical audience. Sure, the audience may have loved Nina’s empowered, sexualized Black Swan, clearly enough to forgive the earlier screw up as the White Swan, but that isn’t surprising if you read the audience as a metaphor for society (why not?), a society that loves more than anything to be seduced by its women.

——————————-

We still have more to say! Let the conversation continue in the comments section, and leave links to reviews you’ve written or read.

Ripley’s Pick: The No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency

|

| The No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency |

Guest Writer Wednesday: Let This Feminist Vampire In

Movie Review: Inception

|

The plot of Inception is deceptively simple: a tale of corporate espionage sidetracked by a man’s obsession with his dead wife and complicated by groovy special effects and dream technology. As far as summer blockbusters and action/heist/corporate espionage movies go, it’s not bad. Once you get beyond the genuinely beautiful camera work and dizzying special effects, however, you’re not left with much.

One thing that really bothers me about the film–aside from its dull, lifeless, stereotypical, and utterly useless female characters (which I’ll get to in a moment)–is that nothing is at stake. Dom Cobb (Leo DiCaprio) and his team take on a big new job: one seemingly powerful businessman, Saito (Ken Watanabe), wants an idea planted into the mind of another powerful businessman, Robert Fischer (Cillian Murphy). Specifically, Saito wants Fischer to believe that dear old dad’s dying wish was for him to break up the family business, so that, we assume, Saito wins the game of capitalism. Should the team go through with the profitable job? We aren’t supposed to care about the answer to this question or what is at stake in the plot.

It’s assumed that, of course we want Cobb to win because he’s really Leo, and, you see, Leo is talented but Troubled. What troubles him? You guessed it: a woman. A woman whose very name–Mal (played by Marion Cotillard, an immensely talented actress who’s wasted in this role)–literally means “bad.” Who or what will rescue Cobb/Leo from his troubles? You guessed it again: a woman. This time, it’s a woman whose very name–Ariadne (played by Ellen Page in a way that demands absolutely no commentary)–means “utterly pure,” and who is younger, asexual (a counter to Mal’s dangerous French sexuality) and without any backstory or past of her own to smudge the movie’s–and her own–focus on Cobb/Leo. So, it’s not a stretch here to say that Cobb needs a pure woman to escape the bad one. Virgin/whore stereotype, anyone?

SPOILER ALERT

So, what makes Mal so bad? In life, she was his faithful wife (for all we know) and mother of his two children. In the film, she’s not even a real woman, but a figment of Cobb’s imagination, haunting him with her suicide. (Note: For a better version of this story, see Tarkovsky’s Solaris, or the crappy Soderbergh adaptation starring George Clooney.) Her constant appearances threaten Cobb’s inception task, and while we can imagine a suicide haunting this hard-working man, we learn the much uglier truth later: while developing his theory of “inception,” Cobb used Mal as his first test subject–planting the idea in her mind that reality was not what she believed it to be. Now we have a main character who exacted extreme emotional violence on his wife, driving her kill herself–yet she’s the evil one.

What makes Ariadne so pure? It’s simple, really. We know she was a brilliant student of architecture, and…and…and…that’s it. The film needed an architectural dream space that wouldn’t be marred by trauma, or memory, or the like, so the natural choice would be for a computer program to design it, right? But a computer program couldn’t also counsel Cobb through the trauma of his wife’s suicide and, ultimately, coach him through killing her apparition. She is invested in getting through the job, as her life depends on it, but why does she give a damn about Cobb? Because she’s a woman architect, and women are nurturing creatures, right? So, we have a main character who exacted extreme emotional violence on his wife and threatens to kill his entire team through self-sabotage over guilt, but luckily he has one good woman to pull him through.

Is it possible to look differently at these two characters? Even if you read the movie as an allegory of filmmaking/storytelling, we’re still left with women who are sidekicks, and who serve merely as plot devices. Maria of The Hathor Legacy writes

Both Mal and Ariadne are symbols, not real characters, and I think this is reflected in the kinds of lines and characterization each is offered. In a movie where businessmen are dryly humorous, several million dollars are devoted to a man’s daddy-issues, and Dom’s nostalgic love for family is symbolized through a honey-heavy shot of golden light haloing his young moppets’ heads, the wooden-ness and flatness of the lines offered these characters is startlingly noticeable.

In other words, even if you refute the realism of the film and its characters, you’re still left with some major gender trouble. Is Cobb a sympathetic character? No. Do we want his big inception job to work? Don’t care. What I care about, for the purposes of this review, is that we have–yet again–a successful mainstream movie that relies on tired tropes of female characters.

Other interesting takes on Inception:

- Inception Regrets Nothing on Feminist Music Geek

- Five Non-Spoiler-y Things About Inception on the Bitch Magazine website

- Inception: A Feminist Review on Clarissa’s Blog