The Season 1 Team From Left to Right: Superboy, Zatanna, Kid Flash, Rocket, Robin, Miss Martian, Artemis, and Aqualad.

Written by Myrna Waldron.

SPOILER WARNING – No major plot twists are revealed, but there are minor spoilers.

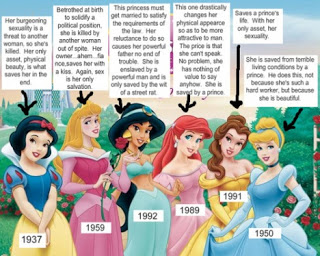

It’s a sadly accepted fact that the superhero genre just isn’t women-friendly. The few times we have gotten a major motion picture centered around a female superhero (Supergirl, Catwoman, Elektra), the results have been abysmal to say the least…leading executives to conclude that superheroines aren’t cost-effective (of course). Films based in both the DC and the Marvel universes all star male superheroes, with heroines only appearing in ensemble groups like X-Men, Fantastic Four and The Avengers (curiously enough, all Marvel properties). It doesn’t look like this is going to change any time soon, since all of the upcoming superhero blockbusters are sequels and reboots to already established male-centric franchises. I fully expect Batman to be rebooted AGAIN before we get a Wonder Woman film.

So it was with trepidation that I started watching Young Justice, an animated TV series centered around the teenage protégées of the members of the Justice League. Produced by Greg Weisman, who created cult classic animated series Gargoyles, I was encouraged by Weisman’s involvement in the show, as Gargoyles’ heroine Elisa Maza is a rare animated lead character who is not only fully competent and well developed, but is also a POC, (Person of Colour) as she is half African-American, half Native American. The series is definitely aimed at a teenage audience, as it has an overarching storyline (rather than self-contained episodes), moral ambiguities, and romance (naturally). Over the course of the first season (Young Justice is now currently in its second season) the teenage team gradually forms, with a combination of well-known and obscure characters, male and female, human and non-human, and white and racial minority. The main cast is as follows:

Green Arrow, Aquaman, Flash and the four protégées, Speedy, Robin, Aqualad and Kid Flash

Robin/Dick Grayson, Batman’s very well known protégée, who is talented with acrobatics, explosives, and computer hacking.

Aqualad/Kaldur ‘Ahm, Aquaman’s protégée, who is Atlantean, so he has the powers of water breathing and manipulation of electricity and water “blades.” Although non-human, he has the appearance of a young black man with blonde hair.

Kid Flash/Wally West, The Flash’s nephew, who, while not as fast as his uncle, has the same super-speed abilities.

Superboy/Conner Kent, a weeks-old clone using Superman’s DNA. He has most, but not all, of Superman’s powers, including super-strength and invulnerability. He lacks the heat-vision, x-ray vision and flying abilities, but can still, as they say, leap tall buildings with a single bound.

Miss Martian/M’gann (Megan) M’orzz, a green-skinned Martian immigrant who is the first female character introduced. Initially pretends to be the niece of Martian Manhunter to conceal a secret about her true Martian identity. She has by far the most powerful and varied abilities, including telepathy, mind-reading, super-strength, flight, shapeshifting, and most importantly, pilots a biological ship that the team uses to travel to their assignments.

Artemis/Artemis Crock, Green Arrow’s protégée posing as his niece. Predictably, she has the same abilities as Green Arrow, including incredible accuracy in archery, use of arrowheads with varying effects (explosive, etc), and general martial arts abilities. Although blonde, she is eventually revealed to be half Vietnamese.

Zatanna, the daughter of Zatara. She has highly varied magical abilities, which require a spell to be spoken in reverse order. Although powerful, her father still outclasses her.

Speedy/Red Arrow/Roy Harper, Green Arrow’s previous protégée. Went solo and renamed himself Red Arrow after still being treated like a sidekick during his introduction to the Justice League. Has the same abilities as Artemis, and only assists the team occasionally.

Rocket/Raquel Ervin, the apprentice of Icon. Gets her powers from her inertia belt, alien technology that grants her the ability to manipulate kinetic energy for flight, super-strength and as a force field. Like Icon, she is (or at least appears to be) African-American.

As a general whole, the equality between the sexes on the team, and the inclusion of several characters of colour, is encouraging. However, the series takes far too long to get to this point. I was incredibly dismayed to notice that for the first episode and 95% of the second episode (which premiered together as a “movie”) no female characters speak at all. Other than Aqualad, the first two episodes are, well, a white sausage-fest. Miss Martian is introduced at the very end of the second episode, and remains a token female for several episodes more. Black Canary, a Justice League member, is assigned to train the team in hand-to-hand combat, (which is a good idea, as it establishes a female hero in a position of leadership and competence) but only appears in episodes occasionally. Artemis is not introduced until the 6th episode, with Zatanna and Rocket joining in the 15th and 25th episodes respectively. Considering that the first season is only 26 episodes, that’s pretty sad.

The series also takes a very long time to pass the Bechdel Test. For those who are unfamiliar with this term, the Bechdel Test is used to help determine female representation in film & television. In order to pass, the media must A) Have two or more named female characters, B) Who talk to each other, C) About something other than a man. Unfortunately, while Miss Martian and Artemis talk to each other, they only talked about the male members of the team (and especially about Superboy, as there is a very minor love triangle surrounding him).

Artemis: You embarrassed Superboy!

Megan: Didn’t hear him say that. Must you challenge everyone?

Artemis: Where I come from, that’s how you survive.

Cheshire and Artemis

The series does not pass the test until the 12th episode during a flashback scene depicting a younger Artemis begging her sister (antagonist/anti-hero Cheshire) not to run away from home in order to escape their abusive father.

Cheshire: You should get out, too. I’d let you come with me, but you’d slow me down.

Artemis: Someone has to be here when Mom gets out.

Cheshire: Haven’t you learned anything? In this family, it’s every girl for herself.

Fortunately, after this barrier is finally broken, conversations between the female characters become a regular occurrence, including sequences where Megan and Artemis team up, and an entire subplot in one episode centred around Artemis and Zatanna having a “girl’s night out” and fighting crime together after Artemis discovers that Megan and Conner have become a couple.

Artemis: (seeing a crime scene with police presence) Whatever happened here is over. I want some action.

Zatanna: Then maybe you need to talk…about Conner and Megan..or whatever.

Artemis: What I need is something to beat up.

The female characters in the show are generally well developed, with Miss Martian getting the most attention and development. It’s a little unfortunate that a lot of the character development surrounding Megan and Artemis is about their romantic entanglements with Superboy and Kid Flash respectively, but that is not unusual for a teenage audience show. One thing I appreciated was that Megan and Conner become a couple fairly early on (the 11th episode) rather than spending an entire season with endless sexual tension (which, unfortunately, is what happens with Artemis and Wally).

Speaking of which, I also have to say how much Kid Flash annoys me. His treatment of women is pretty deplorable; he constantly flirts with Megan despite her total lack of interest, and butts heads with Artemis due to his resentment at her replacing Speedy/Red Arrow.

Red Arrow and Artemis argue while Green Arrow looks on

Artemis: (teasing Wally, who was preparing to go to the beach) Wall-man! Love the uniform. What exactly are your powers?

Wally: Uh, who’s this?

Artemis: Artemis. Your new teammate.

Wally: Kid Flash. Never heard of you.

Green Arrow: Um, she’s my new protegee.

Wally: W-what happened to your old one?

Roy: Well, for starters, he doesn’t go by “Speedy” anymore. Call me Red Arrow.

Green Arrow: Roy! You look —

Roy: Replaceable.

Green Arrow: It’s not like that, you told me you were going solo.

Roy: So why waste time finding a sub? Can she even USE that bow?

Artemis: Yes. She can.

Wally: WHO ARE YOU?

Artemis & Green Arrow: I’m/She’s his/my niece.

Dick: Another niece?

Kaldur: But she is not your replacement. We have always wanted you on the team. And we have no quota on archers.

Wally: And if we did, you KNOW who we’d pick.

Artemis: Whatever, Baywatch. I’m here to stay.

Miss Martian and Artemis in general are not treated as equals until later; Megan makes an honest mistake in one battle (she assumes that an antagonistic android with wind powers is their “den mother” Red Tornado, who has similar powers and implied he would be testing them) and is made to feel foolish for it, and Artemis is treated like an outsider due to the team’s loyalty to Roy. Both are distrusted for their general lack of practical battle experience, despite Superboy being theoretically just as inexperienced. He may be invulnerable, but he is literally months old and is extremely rash and sullen. His impulsive actions during the 5th episode, where he abandoned the team’s mission to fight an enemy on his own, jeopardized the team’s safety far more than Miss Martian’s mistake did earlier, and yet he does not have to endure nearly as much blame and condescension as she did.

Superboy: You tricked us into thinking Mr. Twister was Red Tornado!

Aqualad: She didn’t do it on purpose.

Robin: It was a rookie mistake. We shouldn’t listen.

Kid Flash: You are pretty inexperienced. Hit the showers. We’ll take it from here.

Superboy: Stay out of our way.

Miss Martian: I was just trying to be part of the team.

Aqualad: To be honest, I’m not sure we really have a team.

In terms of racial representation, although the Young Justice team is still primarily comprised of white heroes, having three major characters that are racial minorities is better representation than usual. The alien heroes, Miss Martian and Superboy, also serve as metaphorical representations of racial minorities through their, well, alienation from the team members native to Earth. Although it is tricky to show inclusiveness and diversity without looking like a cheesefest from the 90s, there is definite room for improvement – ideally, the ratio between white and minority characters should be at least 50-50. In addition to this, I was somewhat uncomfortable by Kaldur’s character arc; as the most mature member of the team he is a natural leader, but makes it clear he eventually plans to step down once Robin comes of age. It has been previously established that Robin is usually the leader of these teen teams, and he is by far the most well-known character, but it seemed problematic that the racial minority is acquiescing his position of leadership to a white male.

Another area of representation that needs to be improved is inclusion of LGBTQ characters. So far, all of the romantic relationships depicted in the show have been heterosexual. While not every character has had their romantic interests explored, none have been established as LGBTQ either. If the formerly staid, heterocentric and whitewashed Archie Comics can reinvent itself to include permanent minority and gay characters, there’s no reason that a TV show that skews towards an older audience cannot do so. It would be even more exceptional and encouraging, albeit unlikely, if there was a trans* character introduced in the series, as it is unfortunately very uncommon to see trans* characters represented in the media.

The Season 2 Team, Clockwise From Left: Robin II, Wonder Girl, Lagoon Boy, Bumblebee, Batgirl, Miss Martian, Beast Boy, Superboy and Blue Beetle.

On the bright side, the writers and producers of Young Justice are definitely improving on some of the criticisms I have detailed here. As I mentioned, although the series starts off with far too much emphasis on white male characters, more female characters and more minorities are gradually added to the cast. The second season improves on this even further by introducing even more minority and female characters, including Batgirl, Beast Boy (who, although originally a white male, is technically no longer human), Blue Beetle (who is Hispanic), Bumblebee (who was DC’s first black female superhero), Lagoon Boy (another Atlantean like Aqualad, but less human in appearance), and Wonder Girl. Other additions to the cast in the second season include Tim Drake, who assumes the Robin title after Dick Grayson becomes Nightwing, and Impulse, The Flash’s grandson from the future.

The series also is notable for having a very mature storyline. As I mentioned earlier, the episodes are not self-contained, but all form one continuous plotline. Themes such as sacrifice, wanting to prove oneself, child abuse, and living in someone else’s shadow are prevalent, as well as moral ambiguities such as the implications of being a clone, accepting a parent who is a former convict, and whether antagonists have (human) rights and if the ends justify the means. There are also subtle representations of sexuality, as in the second season some characters are depicted cohabiting, and others having shown to have married and had a child. Previous animated series based on DC comics such as Justice League, Team Titans and Batman: The Animated Series, which all had mature, morally ambiguous stories, are an obvious influence here.

As a general whole, I was very pleasantly surprised with Young Justice once it got over its initial speed bumps. It’s still got a long way to go, but I can say fairly confidently that the representations of women and POC are head-and-shoulders above many other contemporary animated series. The second season indicates that the writers and producers have learned from their mistakes, and are becoming more inclusive as the series goes on. In fact, one popular scene in the fifth episode of the second season points out how absurd it is that an all-female team is considered unusual.

Nightwing: …but Biyalia’s dictator, Queen Bee, is another story. Her ability to control the minds of men is why Alpha is an all-female squad for this mission.

Batgirl: Oh REALLY? And would you have felt the need to justify an all male squad for this mission?

Nightwing: Uh…ahem. There’s no right answer for that, is there? Uh…Nightwing out.

Batgirl: Queen Bee isn’t the only one who can mess with a man’s mind.

The series will be resuming the second season this fall. I look forward to seeing just how much better the series can get in terms of equal representation. Like its teenage protagonists, Young Justice itself is growing up.

All images gratefully borrowed from the Young Justice Wiki.

Myrna Waldron is a feminist writer/blogger with a particular emphasis on all things nerdy. She lives in Toronto and has studied English and Film at York University. Myrna has a particular interest in the animation medium, having written extensively on American, Canadian and Japanese animation. She also has a passion for Sci-Fi & Fantasy literature, pop culture literature such as cartoons/comics, and the gaming subculture. She maintains a personal collection of blog posts, rants, essays and musings at The Soapboxing Geek, and tweets with reckless pottymouthed abandon at @SoapboxingGeek.

Sailor Moon/Usagi Tsukino:

Sailor Moon/Usagi Tsukino:

Sailor Mars/Rei Hino:

Sailor Mars/Rei Hino:

Sailor Venus/Minako Aino:

Sailor Venus/Minako Aino: Sailor Chibi-Moon/Chibiusa Tsukino:

Sailor Chibi-Moon/Chibiusa Tsukino: Sailor Pluto/Setsuna Meioh:

Sailor Pluto/Setsuna Meioh:

Sailor Neptune/Michiru Kaioh:

Sailor Neptune/Michiru Kaioh: