[youtube_sc url=”http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TXwCoNwBSkQ”]

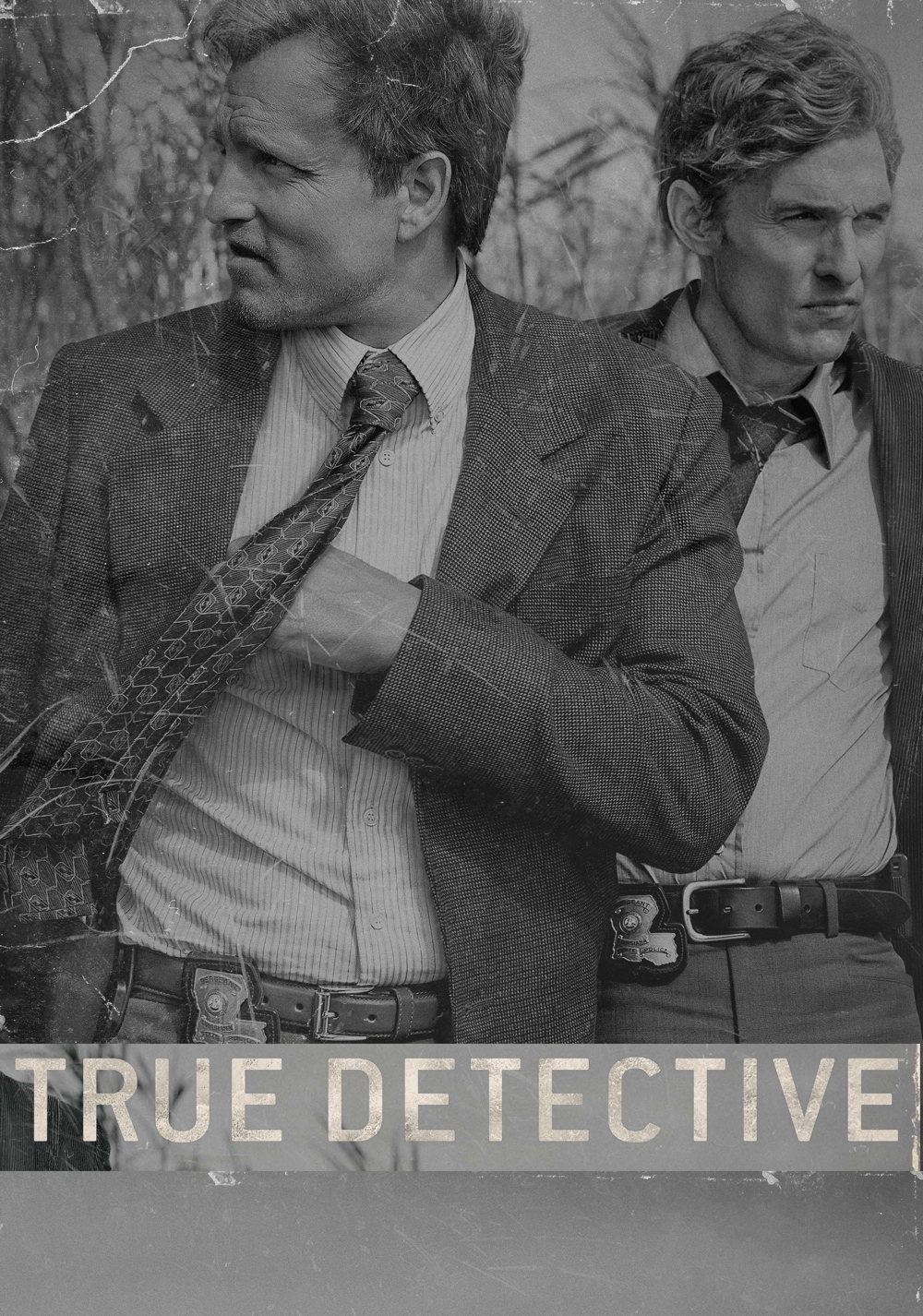

HBO’s newest miniseries True Detective, starring Matthew McConaughey (Rusty) and Woody Harrelson (Marty), has already spawned a substantial cult following, receiving universal acclaim, and it’s only just reached the halfway point at episode number four.

If you’re not watching it, you should be. True Detective is being hailed as the “rise of the miniseries” (following on the heels of the mini-series sweep at the 2014 Golden Globes), a continuation of the TV excellence that has, and will continue to drastically reshape our visual storytelling experience (that’s a big claim, but one to bet on in the coming years).

At the forefront of the True Detective conversation is its subversion of the overdone police procedural (finally) and its meshing of gritty realism and drug-fueled surrealism, creating narrative that is both poignant and disturbing. Its scenes blend sharp, cynical dialogue with the ever-changing landscape of rural Louisiana.

The cinematography is fantastic; episode four, “Who Goes There” features a visceral, though down to earth, six-minute, one shot, gun fight (meaning one take through several houses, a few backyards, and one chain link fence). The scene overwhelms when contrasted with the highly edited, over-wrought action scenes we are spoon-fed at every Hollywood blockbuster and police drama. In fact, the scene orchestrated by Cary Fukunaga is so impressive, many are calling it the best scene of the TV season.

The soundtrack is throbbing, underplaying the simple actions of a police investigation and turning it into an event of greater significance: This is isn’t just a race to stop a serial killer, it’s a metaphor for the battle of good and evil, punctuated by Nic Pizzolatto’s intricate character studies of Rusty in his obsessive nihilism and Marty’s downward spiral.

Yet, for a show that is steeped within the masculinity of a 1996 rural Louisiana police station, and the personal crises of its two male leads, how are the women of True Detective faring? Its women are murdered and raped, wives and prostitutes, stenographers and secretaries. In short, the gritty brush with which Pizzolatto has painted Rusty and Marty has been used on the female cast as well.

However, some of True Detective’s women are all the more compelling because of their flawed station in life, and not just because it’s sadly accurate. In 1991, less than 9 percent of the US police force was female, so the fact that these women operate within in a different capacity doesn’t make the show any less forceful.

In fact, the ways that these women, varied, and often pitiful, demonstrate an adaptability and survival for their incredibly hostile environment, takes a prominent role in the mini series; since True Detective shows so much of Louisiana during their search, it similarly shows much of its women (especially within the confines of poverty).

As the show progresses, one character in particular shines (if you want to call it that) in his interactions with women: Marty. The easy possession that “family man” Marty exerts over the women in his life, beginning to show a penchant for violence in his need to continue that dominion towards his wife Maggie (Michelle Monaghan) and girlfriend Lisa (Alexandra Daddario), is the key factor in showing Marty’s breakdown.

Yet, for all of the effort to steep his characters in realism, some would argue that True Detective still relies on sexist cliché to communicate it’s character failings; Sean Collins of Rolling Stone points out:

“But the idea of a mistress not understanding that’s all she’s supposed to be good for, besides being sexist points back to the show’s reliance on stock characters.”

And Collins might have a point there; so far, the show has featured a lot of women as victims. Though in episode two, “Seeing Things,” the dame of a whorehouse (a sort-of victim) offers an either brilliant, or crazy, provocative reason for prostitution.

Dame: “What do you know about where that girl’s been? Where she come from?…It’s a woman’s body ain’t it? A woman’s choice”

Marty: “She doesn’t look like a woman to me. At that age she’s not equipped to make those choices, but what do you care as long as you get your money?”

Dame: “Girls walk this earth all the time screwing for free, why is it you add business to the mix and boys like you can’t stand the thought. I’ll tell you why, its cause suddenly you don’t own it the way you thought you did.”

Which is an interesting foreshadowing to Marty’s violence when he later discovers that the woman he is having an affair with is also seeing someone else. The line itself, “you don’t own it the way you thought you did,” is particularly meaningful when aimed at the wandering possessiveness of Marty; however, outside of the episode, it enters the heated discussion on female sexuality, shame, and the commercialization of the female body.

This comes around to the tagline for the show, “Heart of Darkness,” an obvious play on words from Joseph Conrad’s classic novella about the African jungle, Heart of Darkness, (fitting since Pizzolatto spent several years teaching literature and writing in academia). For True Detective, the audience is left wondering, is the “Heart of Darkness” the Louisiana landscape? A metaphor for the state of humanity? Or a more literal casting of the two heros’ state of being?

Effective, especially considering that HBO’s website pops up as “Touch the Darkness” (and “Darkness Becomes You”), inviting the audience to experience the demons without, and the demons within.