This guest post by Stephanie Brown appears as part of our theme week on Sex Positivity.

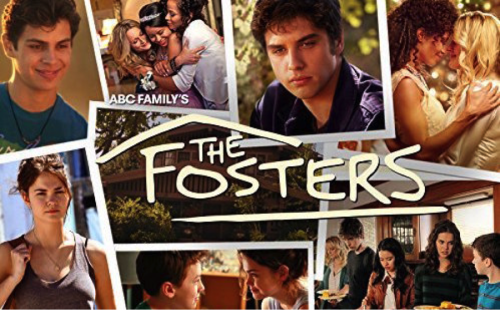

In my frequent lectures to friends about why they should take time out of their busy television (and real life) schedules to watch ABC Family’s drama The Fosters (2013-present), I usually refer to an exchange from the season two episode “Mother Nature” in which Stef (Teri Polo) and Lena (Sherri Saum) have an argument born out of a season-long simmering tension over their respective parenting roles:

Stef: Please stop making me feel like I have to the disciplinarian dad in this family.

Lena: That’s awfully heteronormative thinking.

The first time I watched this episode, I actually paused the show to process my excitement over the fact that a TV show ostensibly for teenagers included a casual reference to the social construction gender roles. Can you name many other shows on basic cable in which you could hear the word “heteronormative” being thrown around? Though, I shouldn’t have been surprised. Over its first three seasons, I’ve been impressed many a time with the range of complex issues thoughtfully addressed by The Fosters, from societal issues of racism, the broken foster system, addiction, and religion to familiar teenage issues like friendship, school, and rival dance teams.

The Fosters, if you aren’t familiar, centers around Stef and Lena and their brood of biological, adopted, and foster children. I will admit that the title of the series is a little (OK, very) on the nose, but I’m willing to forgive it a series that, as you may have gathered, features characters and stories that we don’t usually get to see on TV. The inciting incident for the pilot is that Stef, a cop, and her wife Lena, a high school principal, decide to foster Callie (Maia Mitchell) and her younger brother Jude (Hayden Byerly) after they have been through a series of abusive foster homes. The Adams-Foster family also includes Brandon (David Lambert), Stef’s son from her previous marriage to her police partner Mike (Danny Nucci), and twins Mariana (Cierra Ramirez) and Jesus (Jake T. Austin and Noah Centineo due to a Roseanne-like recasting situation) who were adopted by the family when they were toddlers.

The Foster-Adams family is a big, loving, messy group, which fits well into the network’s “A New Kind of Family” brand. Since ABC Family rebranded in 2006 with this new slogan, they have produced several engaging, interesting, underappreciated dramas. From Greek (which Entertainment Weekly once referred to as “better than it has any right to be”) to Switched At Birth, a show in which scenes are frequently shot completely in sign language, the network frequently spotlights characters and storylines you won’t find anywhere else on television. Of course, as with most pop culture associated with teenage girls, the network’s innovative storytelling is often banished to the world of non-serious TV (a fate that befell the WB, UPN and now the CW as well).

Of course, as you might expect from a show that centers on a family with five teenagers, sexuality is a prevalent theme in The Fosters. Not only do the teenagers on the show deal with issues like having sex for the first time, sexual assault, the questioning of their sexuality, and love triangles, but refreshingly, Stef and Lena also deal with their own adult sex life. While same-sex couples are often desexualized (see Modern Family), Stef and Lena are given storylines that revolve around sex. In one such episode. Lena and Stef have frank discussions about the effect their busy lives and big family is having on their physical relationship and Lena’s fear of succumbing to “lesbian bed death” (2. 16). Stef and Lena not only talk about sex, they’re also shown cuddling post-sex, kissing, and generally showing physical affection for each other. Not only does the series treat sex as a multifaceted an integral aspect of adult relationships, it of course, also normalizes lesbian sex, which has historically either been ignored or relegated to the realm of the salacious male gaze.

The other notably refreshing aspect of Stef and Lena’s on-screen parenting is the way in which they often have to navigate their dual roles as feminists and parents of teenagers. As a woman who doesn’t have kids, I can’t identify with complexities of parenting while feminist, but as a feminist I can absolutely identify with the complexities of living in the world while feminist. To this point, the series raises important questions about the often challenging task of applying our deeply held feminist ideals our messy, everyday lives. I know, for instance, that the unholy alliance between advertisers, the beauty industry, and patriarchal constructions of gender and beauty have combined to make me think twice before leaving the house without putting on mascara. And yet.

In Stef and Lena’s case, they face the much more complicated question of how to talk to their kids about sex in a way that balances their feminist ideals of sex positivity with their parental need protect and discipline their kids. Two scenes in particular stand out to me as exemplars of the ways in which Lena and Stef strive to make sure their kids are not ashamed of their sexuality while simultaneously conveying the importance of being safe, ready, and responsible.

In the season two finale, “The End of the Beginning” (2.21), 13- year-old Jude confides in Lena that he and his friend Connor had made out in their tent on a school camping trip. When he breaks down crying out of a mix what is likely fear, relief, and guilt at having lied to his parents about what happened, Lena makes sure he understands that he has nothing to be ashamed for acting on his attraction to Connor, while reminding him that school-sanctioned trips are not the place to fool around. Similarly, in the summer finale of season 3, “Lucky” (3.10), Lena and Jude have the sex talk after Connor’s dad finds him and Jude making out in Connor’s room:

Jude: So, I’m not in trouble?

Lena: No. No, but you’re probably going to wish you were. I think it’s time we had the talk. I’m really happy that you found someone as wonderful and as kind as Connor. I really am. And when sex is shared between two people…

Jude: OK, OK. Connor and I are not having sex.

Lena: Oh, OK, good. Good. Um, so. When any kind of physical intimacy is shared between two people who care about it each other. It’s a beautiful thing. I mean, OK look, if I’m being honest, I don’t really know a whole lot about the logistics of two men being together, but I definitely want you know how to take care of yourself, and to be safe when the time comes. Which hopefully won’t be for quite some time.

Again, Lena walks the line between reassuring Jude that sex is wonderful and normal, while at the same time making it clear that she hopes that he waits until he is mature enough emotionally, physically, and mentally.

In Mariana’s case, the conversation with her parents happens after she has already had sex for the first time, though under less-than-ideal circumstances. Mariana had planned to have sex with her boyfriend, but when he asks her to wait until he gets back from his band’s tour, she takes his delay as a rejection and ends up hastily having sex with Callie’s ex-boyfriend (“Wreckage,” 3.1).

After harboring a guilty conscience for several episodes, Mariana finally comes clean to her moms in “Going South” (3.5). Throughout the initial conversation, Mariana is defensive of her choice as her moms struggle not to shame her while simultaneously trying to understand her decision.

Stef: Losing your virginity at 15 is a big deal, Mariana.

Mariana: I thought you guys were feminists

Lena: Don’t play that card. We said the exact same thing to your brothers.

Stef: I don’t understand why you think that this is some kind of race.

Mariana: Well I did, OK? And I’m not a virgin anymore, so.

Lena: Honey, I think what your mother’s trying to say is that we love you and we just want to understand your choices.

There is tension not only between Mariana and her moms, but also between Stef and Lena as they negotiate how to handle the situation as parents and feminists. Mariana, knowing her moms well, goes so far as to play the “feminism” card, seemingly daring them to make her feel ashamed of her decision so she can claim the moral high ground by calling out their hypocrisy. In a follow-up conversation, the issue is resolved as Stef and Lena reassure Mariana that she should not be ashamed of having sex or of making a mistake.

Stef: I wasn’t trying to shame you, Mariana. I wasn’t.

Lena: But sex is a big deal. Every time you have sex it’s a big deal. You’re sharing a vulnerable and precious part of yourself. You should always make sure you feel good about it.

Similar to Lena’s conversation with Jude, the goal of the “sex talk” isn’t to scare or shame their kids away from sex, but rather to encourage them to take sex seriously and wait until they’re ready. Stef and Lena also want to assure Mariana that they love her unconditionally, and that our mistakes don’t make us bad people, they make us human:

Stef: My love you know what. We all do things we wish we hadn’t. But we learn from them. And if we manage not to repeat them, man, it feels really, really good.

The talks that Stef and Lena have with Mariana and Jude about sex are emblematic of the way the series treats a range of sensitive subjects with care, warmth, and complexity. As with every situation, Stef and Lena strive to ensure that their kids feel, above all else, unashamed, supported and loved. Of course, The Fosters is by no means a perfect show. It can veer into sentimentality and overwrought melodrama, but I will happily take being manipulated into tears (I was a fan of Parenthood, after all) when it comes with a side of progressive storylines about family, sexuality, and gender. As one of the few shows my mom, my sister and I all watch, The Fosters is a series I hope families across the country are also watching and enjoying together.

Stephanie Brown is a television, comedy, and podcast enthusiast working on her doctorate in media studies at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. You can follow her on Twitter or Medium @stephbrown.