YouTube Break: Buffyverse Season 1 Trailer

Buffy the Vampire Slayer is a series that redefined television in many ways. It combined drama, comedy, romance, action, and horror in an original and unique way. It portrayed a lesbian relationship as mainstream. It centered around metaphors for the trials and tribulations of everyday life that all its viewers, young and old, could relate to. But most importantly, creator Joss Whedon fashioned a world in which the stereotypes of teenage girls (and ultimately all women) were debunked and left at the wayside.

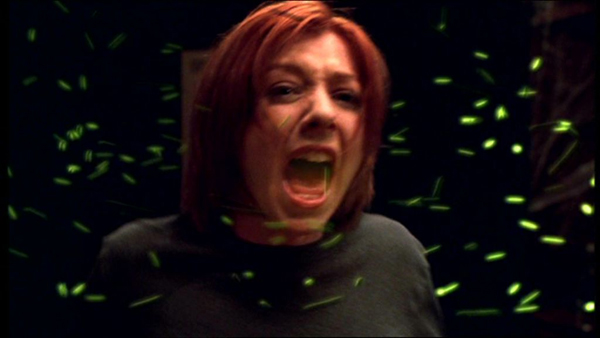

As a lover of Buffy and a theologian, I want Buffy to be theologically and metaphysically coherent. I want it eitherto establish one metaphysical system as true for the world it portrays, or to represent a believable variety of metaphysical beliefs among its characters. The former is an entirely lost cause; the latter is frustratingly undercooked. Willow’s Judaism is wholly Informed, and her turn to Wicca is entirely to do with magic. There is no sense at all of Wicca (or any other religion) as an ethical code, as a way of making meaning, as a way of personally relating to the world and others in it.

Around dinner tables and over cups of coffee, nearly a decade after the series concluded, I’ve witnessed this discussion unfold time and again. And, I think this is the key interpretative moment: are women, the series asks, dependent on men to create a new field of play? Or might the show call into question the norms and expectations of both genders? The answer to these queries may well be found in Spike’s role in the series’ finale. Certainly a number of conversations turn to Spike’s role. In its layers of ambivalence that call upon men to not only transgress but efface normative boundaries, it points to the latter.

YouTube Break: Buffyverse Season 2 Trailer

And then, of course, Buffy kicked a lot of ass. A very serious amount of ass. Over the course of the show’s seven television seasons, she averted multiple apocalypses. She punned and killed all very large monsters and vampires that she came across. She added clever insult to injury. She never apologized for not being a dumb, weak girl. And it was very physical — in the canon of the show, a Slayer is given extra-human powers of strength, speed and agility. She was a fashionable girl’s girl, and she slayed creatures that go bump in the night. It was Girl Power at its late-1990s peak and taken to an excellent extreme.

Though the show suffers from no shortage of powerful women, the ways in which they relate to one another throughout the series is a constant struggle. This is because the dominant patriarchal paradigm within which the show is operating insists that one powerful woman is a delightful anomaly, but multiple powerful women are a threat to hegemony. By these standards, Buffy, by herself, is set up as a superior paragon of womanhood: strong, independent, sassy, beautiful, smart, courageous, and compassionate. If all women, however, were empowered like Buffy, or even a small group, it would be a subversive threat to male dominance, which is why Buffy and her power are exceptional and solitary. This, in effect, handicaps her, limiting her power.

Xander sexualizes power, instead of maintaining a respectful attitude towards strong women. He lusts for most of the powerful women he meets, good or bad – Buffy, preying mantis lady, Incan mummy, Willow (as she begins to mature), Cordelia, Faith, and Anya. At the same time, he finds himself at odds with this attraction, which manifests into this strange almost self-loathing that drives him to assert dominance. Since he’s a rather awkward boy without strength, he uses his tongue, throwing insults and off-the-mark opinions as “Xander, the Chronicler of Buffy’s Failures.”

YouTube Break: Buffyverse Season 3 Trailer

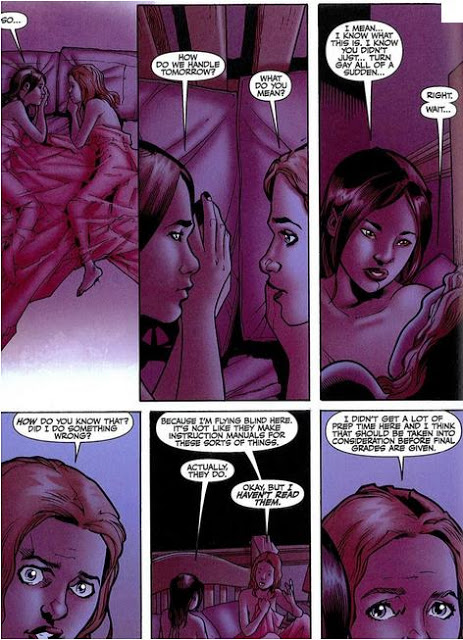

Joss Whedon’s writing for Willow’s dream is clever and filled with misdirection. Characters talk about Willow and her “secret,” a secret that she only seems comfortable discussing with Tara. Dream-Buffy constantly comments on Willow’s “costume,” telling her to change out of it because “everyone already knows.” We’re led to believe that Willow is afraid that her friends will judge her for being gay and being in a relationship with another woman…but this isn’t the case at all.

Instead, when Dream-Buffy rips off Willow’s costume, we see a version of Willow that is eerily reminiscent of season one Willow: a geek with pretensions of being cool.

But its strengths are strengths that none of the other big US dramas have. For one, the flexibility of its form meant that it could be any kind of show it wanted: one week it’s a goofy comedy, the next it’s a frightening fairy tale, the week after it’s an all-singing all-dancing musical. It was clearly the work of a team of writers, too, and when I was young and watching it for the first time it was the first time I really started to learn how TV was constructed – I got a thrill from seeing who had written each episode and guessing at what kind of episode it was going to be by who wrote it. Above all, though, the thing that Buffy has in spades that most shows lack, and the aspect of the show that season five best showcases, is emotion. Even at its most laid back, Buffy is a show spilling over with emotion, and it’s this that gives the potentially goofy premise of show its weight. Whedon et. al. were absolute masters at making us really care about their characters, and every audacious plot contrivance was easily swallowed when viewed through the lens of the real, human emotion that they would imbue it with.

I don’t want to get bogged down about how it sucks in a way that Buffy’s ability comes exclusively from superpowers. I get that, and I could write about it endlessly, but in this moment, I don’t care because Sophia doesn’t care. She watches Buffy and sees a woman who kicks ass, and she wants to emulate that. It’s tough to over-analyze and intellectualize a TV show when you’re watching a young girl practice roundhouse kicks because she wants to be a strong badass like Buffy the Vampire Slayer. And I have to say, it’s much more heartwarming to see her excited about becoming a strong woman with martial arts skills than it was to watch her pretend she couldn’t speak–because she wanted to be Ariel from The Little Mermaid.

YouTube Break: Buffyverse Season 4 Trailer

When the popular movie Twilight first appeared in theaters, it did not take long for fans of Buffy the Vampire Slayer (BtVS) to shame Twilight’s Edward with a fan video smackdown (“Buffy Vs. Edward”). The video shows Edward stalking Buffy and professing his undying love, with Buffy responding in sarcastic incredulity and staking Edward. While it may appear that this “remix” of the two characters was about Buffy slaying a juvenile upstart and reinforcing her status as the queen of the genre, there was more at stake, so to speak. Buffy slaying Edward says more about the perceived masculinity and virility of the vampire in question than about Buffy herself as an independent woman. Buffy was never given that much agency in her own show. Buffy’s lovers stalked her, lied to her, and often ignored her own wishes about their relationships all in the name of “protecting” her. Many of these things are what fans of BtVS pointed out as anti-woman flaws in the narrative of Twilight, yet Buffy did not stake the vampires who denied her agency in her own relationships; instead, she pined for them!

Equality Now: Joss Whedon’s Acceptance Speech by Stephanie Rogers

In 2007, the Warner Brothers production president, Jeff Robinov, announced that Warner Brothers would no longer make films with female leads.

A year before that announcement, Joss Whedon, the creator of such women-centric television shows as Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Firefly, and Dollhouse, accepted an award from Equality Now at the event, “On the Road to Equality: Honoring Men on the Front Lines.”

Watch as he answers the question, “Why do you always write such strong women characters?”

Xander Harris Has Masculinity Issues by Lady T

When I look at Xander through a feminist lens, I find him fascinating because he’s a mass of contradictions. He’s a would-be “man’s man” – obsessed with being manly – whose only close friends are women. He’s both a perpetrator and victim of sexual assault and/or violation of consent. He’s both attracted to and intimidated by strong women. He jokes about objectifying women and viewing sex as some sort of game, but in more intimate moments, seems to value romance and real connection. He’s a willing participant in the patriarchy and also a victim of it.

YouTube Break: Buffyverse Season 5 Trailer

YouTube Break: Buffyverse Season 6 Trailer

So whilst Buffy can defeat demons and save the world over and over, her emotional detachment and self-righteous sense of martyrdom (have some humility woman!) make these fights she doesn’t actually win, absolutely crucial to the Series’ greatness. Ultimately that’s why I find it hard not to let out a little yelp of glee when Dark Willow declares, “You really need to have every square inch of your ass kicked.” Faith, Willow and Anya teach Buffy to lose the ego and remember what she’s really fighting for, and that’s feminism in action right there.

A common criticism of Dawn is that she’s much more immature than the main characters were at the start of the series, when they were close to her in age (Dawn is introduced as a 14-year-old in the eighth grade; Buffy, Xander, and Willow were high school sophomores around age 15 or 16 in Season 1). Writer David Fury responds to this in his DVD commentary on the episode “Real Me,” saying that Dawn was originally conceived as around age 12 and aged up a few years after Michelle Trachtenberg was cast, but it took a while for him and the other writers to get the originally-conceived younger version of the character out of their brains. But I don’t need this excuse; I think it makes perfect narrative sense that Dawn comes across as more immature than our point-of-view characters were when they were younger. Who among us didn’t think of themselves as being just as smart and capable as grown-ups when we were teens? Who among us, when confronted with the next generation of teenagers ten years down the line, were not horrified by their blatant immaturity?

Willow is Whedon’s version of the answer to the underrepresented gay community. But, Willow appears to have had a healthy sexual relationship with her boyfriend Oz, and there is no hint at otherwise. She also pined for Xander for years. Both men. We see her gradually start a relationship with Tara, but she never talks about or reflects on her sexuality or coming out. We see that she is nervous about whether her friends approve. But, it doesn’t get much deeper than that. No characters have a deep conversation with her about her orientation. It’s not a thorough exploration. She goes from being with men to exclusively being with women and identifying as a lesbian. This is fine for Willow, but because there are really not many open gay or lesbian characters within the entire series we are dependent on her narrative alone.

YouTube Break: Buffyverse Season 7 Trailer