|

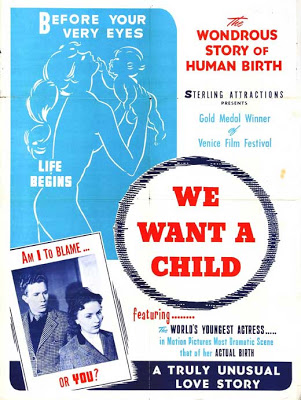

| Movie poster for We Want a Child |

Depictions of any of these subjects are few and far between in modern film and television, so the fact that a feature film was made so long ago is remarkable in itself.

We Want a Child offers a frank portrayal of the emotions involved in trying to build a family.

The film opens with Else and Lief’s wedding. The audience is introduced to a happy bride (who is just doing the church wedding–“veil and everything”–because her mother wants her to) and her playful new husband.

At the celebratory dinner reception, Else’s Uncle Hans toasts the new couple and the unity of the family “up through a new generation.”

Next the audience sees Uncle Hans–a bit of a buffoon–riding his bike over to Else’s house to check on her. “No news?” he says. “No news,” she says. “I don’t want you asking me each week.”

Clearly, the family is waiting for an announcement of Else and Lief’s pregnancy, and Else is already tiring of the requests.

“Two years have gone by…” is superimposed on the screen, and the uncle walks in again. Else is polishing silver, visibly upset, and Hans notes that it’s their two-year anniversary. A puppy walks into the room, and he’s shocked: “You got a dog?”

“I know perfectly well you don’t like to discuss it,” he says, “but why don’t you have kids?”

Else says she wants to enjoy their youth, and that they don’t want children right now. She quickly breaks down, though, and says, “I’m beginning to think I can’t have a child.” Uncle Hans, without judgment, encourages her to see a doctor.

Later Else asks Lief if he wants a baby. “Doesn’t every man?” he says, playfully. She cries and hugs him, saying “What if we can’t have a baby? Maybe I can’t have any.”

Their relationship is portrayed as equitable and loving; they joke and laugh and seem to be deeply in love. When she expresses her fears, he doesn’t belittle her or act uncomfortable. Since the threat of infertility often wreaks havoc in relationships, the depiction of Lief and Else’s relationship throughout the film is refreshing.

Else does visit the doctor, and tells him she’s afraid she can’t have any babies. He asks about her menstruation and rattles off a list of other health questions. He says, “I suppose we don’t have to consider abortion.” Else answers, “Yes, we have to.”

|

| Else confides in the doctor that she’s had an abortion. He judges, but quickly moves on to helping her. |

The doctor takes his glasses off and pauses. She says that it had been an operation a few years ago, and he notes that it was “a criminal abortion.” (Abortion in Denmark was legalized in 1973.)

He stands up, and Else pleads with him, saying she knew it was wrong, but it was during the war and her fiance (now husband) had to go underground. The doctor is judgmental (saying that she “preferred to kill her child” instead of looking for help), but it’s not nearly as damning as one would expect from the time. He goes on to tell her that it might be the reason she hasn’t conceived, and that sometimes abortion causes scar tissue in the fallopian tubes. He tells her they will take x-rays and run some tests.

As Else is leaving the doctor’s office, her friend Jytte is coming in. She’s become pregnant by the married man she’s having an affair with, and he wants nothing to do with her or a baby. Jytte goes in to talk to the doctor, and is clearly upset and unsure of what she wants to do. The doctor urges her to not have an abortion, lest she “deny motherhood” and ruin her chances to have a child in the future after going to a “quack” to have her “body mutilated.” He promises her it’s not as hopeless as she thinks, and she promises to think over it–but not before snapping that a woman should be able to make her own decisions.

After these scenes, the harsh judgment surrounding abortion–which at the time

was a criminal act and wouldn’t have been a safe medical procedure, so conversations about it in a feature film could only go so far–ends.

As Else leaves the doctor’s office, a mother is struggling and Else offers to hold her baby for her. The way she looks at the child is full of love and deep longing.

Jytte decides against having an abortion (even though her lover wants her to).

The doctor shows Else her x-rays–one of her tubes is blocked, but the other side is open. “You have a chance, you can become pregnant,” he says. “You must hope.” He encourages her to tell her husband.

While Else is at the doctor, Lief has befriended a neighbor child, and their interactions are sweet. The bond shows that when a couple wants children but cannot have them, they often still “parent” in other ways, whether it’s a neighbor child, or a dog, or both, in their case.

Else comes home, resolved to tell Lief about her abortion.

“Lief, can you forgive me?” she cries.

He says it’s his fault, but she responds,

“It’s what we wanted, both of us. I should have told you long ago.”

“Don’t worry, darling, we’re together,” he says.

When Lief speaks with Uncle Hans about the fact that “we’ll have to get used to the idea that it’ll be only two” of them, alone, he adds that “the doctor gave her hope, but what else can he say?”

“It’s completely idiotic in a world like ours to want my own children… yet I want them,” Lief says.

Else soothes herself by thinking that they are enjoying their youth. They get a puppy. Lief befriends and mentors the neighbor child. Lief grapples with the fact that it feels selfish to desire biological children, but acknowledges the deep urge. The way the couple deals with and speaks about their infertility is truthful and realistic.

Uncle Hans sees an opportunity, and tells Jytte he knows of a young couple who would like to adopt a baby, and that she can stay with him (since if she becomes visibly pregnant she’ll lose her job and room).

Things seem to be falling in place. The next scene is Lief and the neighbor boy carrying a bassinet upstairs to the nursery. Else’s mother visits, and is rude and dismissive when Lief tells her that Else is visiting their new daughter. “Why on earth are you adopting?” she asks, and he tries to explain that they can’t have one themselves.

Lief goes to the clinic, flowers in hand, to see Jytte and his new daughter. Else steps out of the room, visibly upset. “She said she couldn’t do it,” she says. “She can’t go through with the adoption.”

While she’s upset, Else tells him that they shouldn’t be angry. Lief gives the flowers to the nurse to give Jytte.

At this moment, we see the most tension between Else and Lief. He says he needs to go back to work, and he coldly leaves after saying goodbye. Else is left alone. The scene is harshly realistic.

Back at home, Else’s mother is condemning adoption and Jytte, but Else softly tells her, “You can’t blame her for not wanting to give up her baby.” She quickly runs from the room and gets sick.

Her mother smiles, knowing what the nausea signifies.

Else is excited when she puts the pieces together, but nervous: “I’m more afraid that it isn’t true, or if it is true, it won’t be a healthy child.” Her mother assures her that worrying is part of being a mother. The fear involved with becoming pregnant after infertility is palpable.

Else goes back to the doctor, and he confirms her pregnancy. He asks her about rickets, scarlet fever, hereditary diseases, venereal diseases and he listens to her heart and checks her back.

|

| Else weeps with joy when the doctor confirms her pregnancy. |

“We have to be careful now that we have a responsibility for a new little citizen,” he says. When she asks if he thinks it’s a girl, he says, “Male? Female? It’s a human.”

This segment of the film feels a bit like an educational video for prenatal care–he explains all of the blood tests he’s taking (including testing her rhesus type so they can take care of her properly if it’s negative). Her scenes with the doctor are clearly meant to be instructional to viewers.

Else goes home, and coyly tells Lief that she is “expecting something.” They are both elated.

|

| Else and Lief celebrate the news. |

Her pregnancy progresses normally, and Else wakes up in the middle of the night feeling pain. (The dog, not forgotten, is fully grown in a bed by Else and Lief’s bed.) She and Lief rush to the clinic, and the midwife tells Lief, “Kiss your wife goodbye, we’ll call you when it’s over.” He begs to stay, but the midwife assures him that they’ve “no need” for him. They walk away, and Lief stands alone, staring. He walks home (where he continues to pace and call the clinic for updates).

Else is given anesthesia via inhalation, and the doctor tells her that she’ll “go to sleep, wake up and it will be over and done with.” This is most likely ether, as the drugs that induced

Twilight Sleep were intravenous.

She wakes up, and a nurse hands her a beautiful girl, while Lief stands beside her. “Well, we made it,” he says. They are both beaming.

The baby sneezes (

baby human and

baby animal sneezes are certainly evolution’s way of causing women to spontaneously ovulate), and the film is over.

While there are a couple of moments in the film that will undoubtedly make a pro-choice feminist cringe, the fact that Else is still fertile even though she had an abortion is what’s important. If the film had truly been wholly anti-abortion, she would not have been able to go on and conceive and have a happy ending. Aside from the doctor’s comments (and of course he was acting as a medical and moral authority of the time), Else and Lief are united–and both recognize that an abortion is what they both wanted at the time–and she is not punished.

At the time the film was celebrated in some circles for its clear anti-abortion message, but the fact remains that Else is

not infertile. Her husband isn’t angry that she had an abortion. Everything turns out just fine.

Jytte isn’t punished for her decisions, either. She seems to have a mutually beneficial life at Uncle Hans’s house. Else’s forgiving response to the adoption falling through assures the audience that we are not to be angry with Jytte, either.

|

| Lief visits Else and their new daughter at the clinic. |

The frank discussion about infertility, abortion, prenatal care and adoption make this film noteworthy. It feels quite remarkable to watch characters discuss the range of emotions surrounding these subjects. The film isn’t a masterpiece, and it moves quickly and relies on some common tropes surrounding the topic of infertility and adoption, but some of the dialogue is striking in its honesty and timelessness.

The struggles that infertile couples face in 2013–the fear and guilt that you’ve done something wrong, the desire to have a biological child, the risk of adoption falling through, facing a marriage without children–are no different than they were almost 75 years ago. These struggles, however, are rarely represented on screen. The experience of viewing characters who deal with these life events feels meaningful and important. We shouldn’t have to dig so far and so hard to find them.

* * *

One of the reasons this film dealt so well with these subjects was no doubt its director, Alice O’Fredericks (she directed it with Lau Lauritzen). O’Fredericks was a prolific writer and producer–she wrote 38 screenplays and directed 72 films. Many of her films focused on women’s stories and women’s rights. The Copenhagen International Film Festival annually awards a female director with the Alice Award, named after O’Fredericks.

|

| Alice O’Fredericks, Danish writer, director and actor |

———-

Leigh Kolb is a composition, literature and journalism instructor at a community college in rural Missouri.