This guest post by Ben Cowburn appears as part of our theme week on Male Feminists and Allies.

Despite the recent election of the country’s first female president, South Korea isn’t the easiest place to find examples of gender equality. The country has one of the world’s largest gender gaps (1), a corporate culture still shaped by patriarchal Confucian traditions, and extreme pressure on young women to conform to very particular beauty standards. At first glance, Korean cinema appears to mirror this lack of progressiveness, as in terms of behind-the-camera power, the country’s film industry, which boomed with the Korean Wave of the late 90s, seems to be as much a boys’ club as Hollywood (2). However, the situation for on-screen representations of women and girls seems to be steadily improving in South Korea, driven in part by successful filmmakers who could easily be described as male feminists.

Korea’s most internationally visible writer/directors Park Chan-wook and Bong Joon-ho, and festival favourite Lee Chang-dong, have all crafted films based around female characters at least as complex as the men they come into conflict with. Park’s Lady Vengeance gave Lee Yeong-ae a role as starkly uncompromising as Choi Min-shik’s in Oldboy, and his films I’m A Cyborg but it’s Okay and Stoker both feature female protagonists. Bong’s film Mother is based around a searing performance from celebrated TV actor Kim Hye-ja, and even the seemingly male-dominated Snowpiercer features strong roles for Ko Ah-sung, Octavia Spencer, Alison Pill and Tilda Swinton, who gives one of her most memorably strange performances. Lee’s Secret Sunshine and Poetry feature complex, unglamorous, down-to-earth female protagonists, portrayed in award-winning fashion by Jeon Do-yeon and Yun Jeong-hie.

In the less internationally prestigious corners of the industry, South Korean cinema has developed a crowd-pleasing line in modestly budgeted films with predominantly female ensemble casts. Though often determinedly formulaic, films such as Forever the Moment, based on a women’s handball team, and Harmony (3), set in a women’s prison, are relentlessly entertaining, easily pass both Bechdel and Maki Mori tests, and have proved very popular. The most commercially successful example of this mini-genre is Sunny, released in 2011, and directed by Kang Hyeong-Cheol, who co-wrote the script with Lee Byeong-Heon (4). Both Kang and Lee are men, but Kang reportedly based the story on his mother’s recollections of her high-school life (5), and the film, which is powered by the memorable performances and excellent chemistry of its largely female cast, has a strongly feminist message.

Sunny centres around a clique of seven friends in a Seoul girls’ high school sometime in the 1980s (the film is a little hazy with the actual continuity), who are reunited in the present day, after being estranged for more than 25 years. The film is structured to give equal weight to the friends’ time in high school and to their eventual reunion, and cheerfully ticks off most of the tropes viewers would expect from its set-up. In the high school scenes friendships are forged, sisterhood is strained, bullies are bested, cute guys are crushed on, and families are fought with. In the present day, nostalgic jokes and reveries are shared, disappointments and failures are revealed, and the bonds of friendship are shown to be timeless. All pleasantly predictable and satisfying for fans of coming-of-age stories, and elevated by the playful zest of the film-making, entertaining plot absurdities, and most of all, by the irresistible energy of the cast.

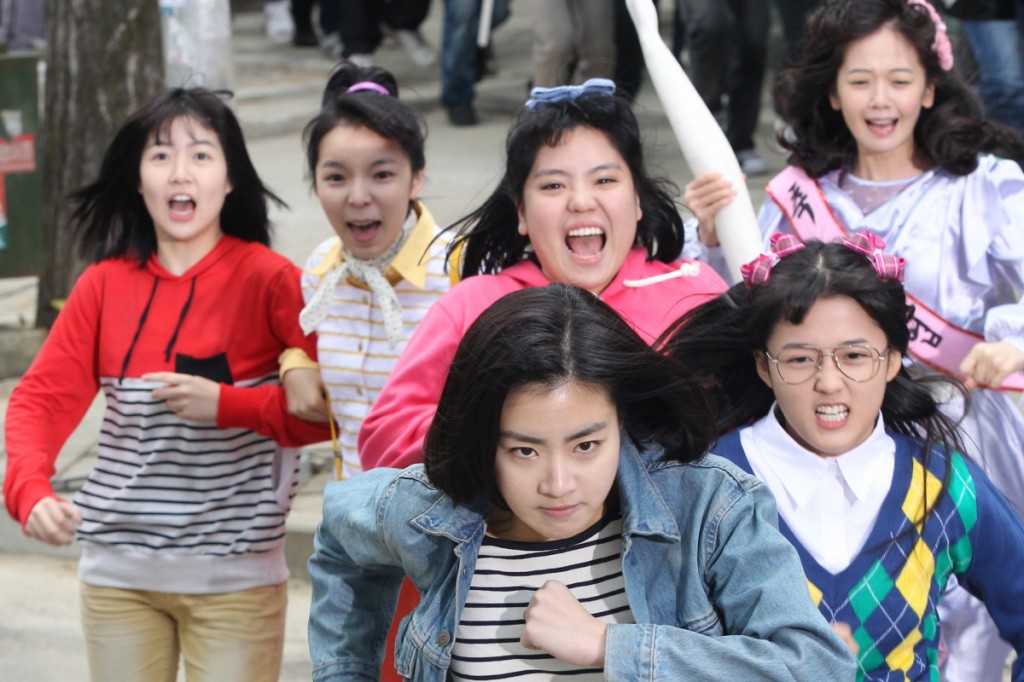

The film is told from the perspective of Na-mi, a newcomer to the school in the 80s, and an under-appreciated wife and mother in 2011. A chance present-day encounter with old friend Chun-hwa leads Na-mi into a series of flashbacks, and sparks an attempt to get the old gang back together. Gang is the right word, as in the flashbacks we see the seven girls trade insults, and eventually punches and flying kicks, with a rival posse from another school. Chun-hwa, the group’s charismatic leader, brings Na-mi into the fold when she proves useful in squaring off against the enemy. Despite some friction (there has to be some friction) with another member, Na-mi is soon initiated into the group, which is given the name Sunny by a radio DJ, and practising a chaotic dance routine to accompany Boney-M’s version of Bobby Hebb’s ode to looking on the bright side.

The 80s scenes are a blur of logo-strewn sports bags, candy-coloured sweaters, synthed-up disco tunes and reverb-heavy ballads. The script mixes in references to current K-pop groups, as well as winking predictions for a future of professional video gamers and “portable phones.” Anachronisms are also cheerfully thrown around: characters mention watching MTV, which wasn’t broadcast in Korea until 1991, and the story plays out against a backdrop of civil unrest, which seems to suggest the student-led June Democracy Movement that flared up in 1980. This turbulent background seems to mainly be set up to allow for a highly entertaining slow-motion fight between the two gangs amidst a melee of riot police and protesters. The ridiculous bravado of the scene, which is clearly filtered through the older characters’ memories of the fight, makes the clunky exposition and obvious expense of the extra-strewn scene completely worthwhile.

The heightened, highly-charged nature of the flashback scenes reflects Na-mi’s nostalgic (and sometimes painful) recollections of her school days, and contrasts nicely with the slightly more subdued style of the present day scenes. At times, the two time periods are swirled together, as in another deliriously weird fight sequence, and in a touching montage in which Na-mi’s teenage disappointment over an unrequited crush is cross-cut with her mid-40s acceptance of a path not taken. Mostly, though, the streams are crossed with playful in-camera transitions, which employ doorways, walls, and windows as time portals, and music as a bridge between periods. A pivotal (and probably obligatory) scene in which Na-mi watches a video recording of the teenage gang members addressing their older selves is adeptly realized, thanks to the vitality of the girls’ ensemble work, and the weaving of on-going conflicts into the video.

There are few scenes in the 80s storyline in which Na-mi doesn’t face an elemental teenage challenge, either from within the gang or from the outside world, and this helps sustain a charged and immediate atmosphere. Though the present-day scenes aren’t quite as potent, they provide plenty of opportunities to underline the important role the girls played in each other’s formative years, and what they have missed out on since high school. The easy, affectionate chemistry between the older actors nicely mirrors the frenetic fellowship of the younger cast, and the present-day scenes deliver plenty of abrasive humour to complement dollops of well-earned sentiment.

The actors in both story-lines brilliantly unify their linked performances, and this was clearly a major focus of the casting and Kang’s work with his cast. Particularly compelling are Sim Eun-kyeong and Yu Ho-jeong as the younger and older Na-mi, and Kang So-ra and Jin Hee-kyung as Chun-hwa, but each member of the gang is sharply defined, especially in the 80s scenes. The characterisation is mostly archetypal, but the girls are all shown to be witty, smart and determined, and no one is bodily humiliated or slut-shamed. In fact, sexuality has only the briefest of roles in proceedings, which is perhaps a little unrealistic, but helps to keep the focus firmly on the friendship between the girls. The single romantic complication is swiftly dealt with, so that the gang can get on with the real business of practising their dance moves, kicking ass and keeping the world at bay with a combination of mutual support and bag language.

Swearing plays a surprisingly important role in the film. Early on Na-mi’s possibly senile grandmother spews out a stream of backwoods invective, which Na-mi later copies to help the gang scare off their rivals and gain acceptance. In both time periods, the friends routinely refer to each other as ‘shibal nyun’ (usually translated as ‘fucking bitch’), and one of the younger gang members dreams of writing a swearing dictionary. The film’s original cut had so much cursing that it to be edited to ensure a PG-15 certificate, which seems to have been the right choice, as the film presents some very positive messages for teenage girls. The director’s cut restores the characters to their full, foul-mouthed glory, which gives scenes in the past and present bite and authenticity, and could be seen as a challenge to the subservient role women are often still tacitly expected to perform in Korean society. Other satirical touches include digs at South Korea’s enduring obsession with very specific beauty ideals, such as “double eyelids,” and the undermining of a male teacher’s army-derived methods of corporal punishment.

The teenage characters have a refreshingly diverse range of ambitions (most of which remain unfulfilled in their present day lives, of course), and they are never objectified or marginalised, with costume design and shot choice underlying another important theme: that each of the girls needs to become the protagonist in her own story. This is somewhat unnecessarily spelled out out at several points, but the film mostly follows through with the idea, only fudging things a little in its final scene, which seems to present money as a key to solve everyone’s problems. More importantly, though, the resolution shows the women learning to take inspiration from their teenage selves, and vowing to reclaim agency in their lives.

Although seemingly machine-tooled to yield maximum comic and emotional impact, Sunny has plenty of rough edges and plot contrivances: Na-mi’s husband is mysteriously called away on a two-moth-long business trip, to give her more time to bond with her estranged friends, and the climactic event that closes the 80s storyline doesn’t convince as a reason for the girls to completely lose touch for a quarter century. The director’s cut, which I watched, could certainly use a trim, with a few unnecessary side stories adding little to the main characters’ arcs. None of this really matters, though, as Kang and his cast manage to cram in plenty of heady scenes of triumph, defeat, affection and antagonism into the 80s storyline, most of which are paid off in the present-day scenes. Do the 40-something friends reunite to perform the dance to Sunny they practised as teenagers? Does each woman find solace and strength in her re-invigorated friendships? Does the dictionary of swearing ever get written? I couldn’t possibly say.

Sunny proved endearingly popular on its cinema release (6), and became the second highest grossing domestic film in Korea of 2011, due in part to a surge in nostalgia for the culture of the 7080 generation, but mainly to strong word-of-mouth. As with Bridesmaids and The Heat, the film clearly shows the huge demand for female-lead films, and like those film’s director, Paul Feig, Kang seems to be a strong advocate for feminism in film. Though South Korea cinema (and the country as a whole) clearly needs far more women in off-screen positions of power, Sunny seems like a small but hopeful step towards equality, and may well inspire girls in today’s high school cliques to one day demand those positions.

1 – South Korea currently ranks number 111 out of 136 in the World Economic Forum Gender Gap Report, and the country has been on a downwards trajectory for the last few years.

2 – All of 50 most popular Korean films to date have male directors.

3 – One of the most successful Korean films with a female director, Dae-gyu Kang, Harmonymade me weep repeatedly when I saw it on a plane a few years ago. I blame the altitude.

4 – Not the devilishly handsome actor of the same name, best known to international audiences from The Good, The Bad and The Weird.

5 – According to a Q+A transcribed here.

6 – The film opened at number in the Korean box office, stayed there the following week, and returned to the top spot five weeks later.

Ben Cowburn is from England, and currently works as an English language teacher in Jinju, South Korea. He also writes and takes photos. Words and pictures, can be found at: thelightthroughthewindow.