Another universally recognized truth of horror is that scary children are terrifying–especially

little girls.While an analysis of

“creepy children” in horror films usually proclaims that they are providing commentary on a loss of innocence, and it would make sense that a little girl is the “ultimate” in innocence, it can’t be that simple. We wouldn’t be so shaken to the core by possessed, haunted, violent

little girls if we were simply supposed to be longing for innocent times of yesteryear.

Instead, these little girls embody society’s growing fears of female power and independence. Fearing a young girl is the antithesis of what we are taught–stories of missing, kidnapped or sexually abused girls (at least

white girls) get far more news coverage and mass sympathy than stories of boy victims. Little girls are innocent victims and need protection.

In the Victorian era, the ideal female was supposed to be pale, fainting-prone and home-bound. Feminist literary icons Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar write about this nineteenth-century ideal in

The Norton Anthology of Literature by Women:

“At its most extreme, this nineteenth-century ideal of the frail, even sickly female ultimately led to the glorification of the dead or dying woman. The most fruitful subject for literature, announced the American romancer Edgar Allan Poe in 1846, is ‘the death… of a beautiful woman’… But while dead women were fascinating, dying girl-children were even more enthralling… These episodes seem to bring to the surface an extraordinary imperative that underlay much of the nineteenth-century ideology of femininity: in one way or another, woman must be ‘killed’ into passivity for her to acquiesce in what Rousseau and others considered her duty of self-abnegation ‘relative to men.'”

The feminine “ideal” (and its relation to literature) coincided with women beginning the long fight for suffrage and individual rights. It’s no surprise, then, that men wanted to symbolically kill off the woman so she could fulfill her ultimate passive role. There was something comforting about this to audiences.

|

| Rhoda Penmark will not lose to a boy. Or anyone else. |

Fast forward to the 1950s and 60s, and the modern horror genre as we know it emerged and began evolving into something that provided social commentary while playing on audiences’ deepest fears (the “other,” invasion, demonic possession, nuclear mutations and the end of the world).

We know that horror films have always been rife with puritanical punishment/reward for promiscuous women/virgins (the

“Final Girl” trope), and violence toward women or women needing to be rescued are common themes. These themes

comfort audiences, and confirm their need to keep women subjugated in their proper place. It’s no coincidence that the 50s and 60s were seeing sweeping social change in America (the Pill, changing divorce laws, resurgence of the ERA, a lead-up to Roe v. Wade).

Terrifying little girls also make their debut in this era. Their mere presence in these films spoke not only to audiences’ fears of children losing innocence, but also the intense fear that little girls–not yet even women–would have the power to overthrow men. These girl children of a generation of women beginning a new fight for rights were terrifying–these girls would grow up knowing they could have power.

The Bad Seed‘s Rhoda Penmark (played by Patty McCormack in the 1956 film), genetically predisposed to be a sociopath, murders a classmate and the janitor who suspects her. Her classmate–a boy–beats her in a penmanship contest, and she beats him to death with her tap shoes. A little girl, in competition with a boy, loses, and kills. While in the novel Rhoda gets away with her crimes, the

Hays Code commanded that the film version “punished” her for her crimes and she’s struck by lightning. It’s revealed that Rhoda’s sociopathic tendencies come from her maternal grandmother, a serial killer. This notion of female murderous rage, passed down through generations and claiming boys/men as its victim, certainly reflects social fear at the time.

In 1968,

Night of the Living Dead premiered on big screens and has been seen as commenting on racism/the Civil Rights movement, Cold War-era politics and critiquing America’s involvement in the Vietnam War. However, little Karen Cooper’s (Kyra Schon) iconic scene has long disturbed audiences the most. Infected by zombies, she eats her father and impales her mother with a trowel. A horror twist to an Oedipal tale, one could see Karen as living out the gravest fears of those against the women’s movement/second-wave feminism. Possessed by a demon, she eats her father (consumes the patriarchy) and kills her mother (overtaking her mother’s generation with masculine force).

|

| Little Karen Cooper consumes patriarchy and overtakes her mother. |

Five years later, Roe v. Wade had been decided (giving women the right to legal first-trimester abortions), the Pill was legal, no-fault divorce was more acceptable and women began flooding the workforce.

Meanwhile, on the big screen, sweet little Regan MacNeil–the daughter of an over-worked, atheist mother–becomes possessed by the devil.

The Exorcist was based on a novel, which itself was based on the exorcism case of a little boy. Of course, the novelist and filmmakers wanted audiences to be disturbed and terrified, so the sex of the possessed protagonist changed (would it be as unsettling if it was a little boy?).

Chris MacNeil, Regan’s mother, goes to great lengths to help her daughter, and resorts to Catholicism when all else has failed. Regan reacts violently to religious symbols, lashes out and kills priests, speaks in a masculine voice and masturbates with a crucifix. This certainly isn’t simply a “demonic possession” horror film, especially since it was written and made into a film at the height of the fight for women’s rights (the Catholic church being an adamant foe to reproductive rights). Only after Regan releases her demon, which possesses a priest (who flings himself out of a window to commit suicide), does she regain her innocence and girlhood.

|

| Tied and bound, Regan haunts and kills men, and reacts violently to religious images. |

What her mother and her culture are embracing–atheism, working women, reproductive rights, sexual aggressiveness–can be seen as the “demons” that overcome the innocent girl and kill men (and traditional religion).

These films are have terrified audiences for decades, and for good reason. The musical scores, the direction, the jarring and shocking images–however, they also play to society’s deepest fears about women and feminism. For little girls to be possessed is the ultimate fall.

In 1980,

The Shining was released. Yet another film adaptation of a novel (Stanley Kubrick’s treatment of Stephen King’s novel), this film contains two of the creepiest little girls in film history–the Grady girls.

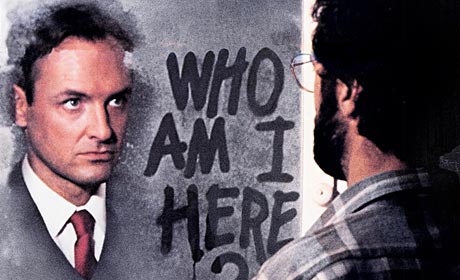

The Shining shines a light on crises of masculinity. Jack Torrance, played by Jack Nicholson, is a recovering alcoholic who has hurt his son, Danny, in the past. When he takes his wife, Wendy, and son with him to be caretakers of a hotel over a winter, his descent into madness quickly begins. Danny has telepathic abilities, and sees and experiences the hotel’s violent past. As he rides his Big Wheel through the hotel, he stops when he sees two little girls begging him to “Come play with us Danny. Forever.” These girls–dead daughters of Grady, a previous caretaker who killed his family and himself–are trying to pull Danny into their world. Danny sees images of them murdered brutally, and flees in fear. Meanwhile, Jack is struggling with his alcoholism, violence and lack of control of himself and his sensitive wife and child. When he sees Grady, Grady advises him:

“My girls, sir, they didn’t care for the Overlook at first. One of them actually stole a pack of matches, and tried to burn it down. But I ‘corrected’ them sir. And when my wife tried to prevent me from doing my duty, I ‘corrected’ her.”

|

| Danny is confronted with the horror of what men are capable of. |

In this aftermath of the women’s movement, Jack (a weak man, resistant to authority) is being haunted and guided by a forceful, dominating masculinity of the past. He’s stuck between the two worlds, and succumbs to violent, domineering alcoholism.

But he loses. Wendy and Danny win.

While his predecessor succeeded in “correcting” his wife and daughters, that time has past.

Here, the flashing memories of the ghosts of the past are terrifying. The Grady girls provide a look into what it is to be “corrected” and dominated.

|

| “Come play with us Danny,” the girls beg, haunting him with the realities of masculine force and dominance. |

Starting with the late-70s and 80s slasher films (and the growing Religious Right/Moral Majority in politics), the “Final Girl” reigned supreme, and the promiscuous young woman would perish first. Masculinity (characterized with “monstrous” violence and strength) and femininity became natural enemies. These fights on the big screen mirrored the fights in reality. The

Equal Rights Amendment was pushed out of favor and was never ratified, and a growing surge of conservatism and family values began dominating American rhetoric.

In the late 90s and early 2000s, we see a resurgence of the terrifying little girl. This time, she is serving as a warning to single/working/independent/adoptive mothers.

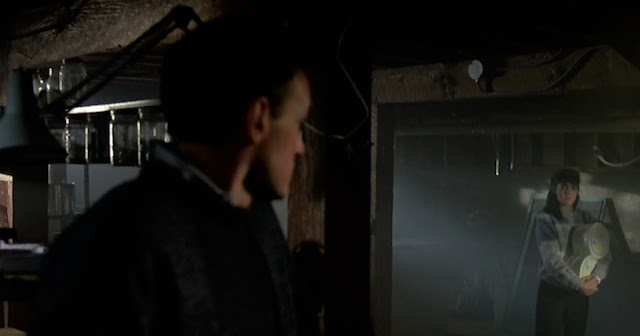

In

The Ring (the 2002 American adaptation of a 1998 Japanese film), Rachel Keller (played by Naomi Watts) is a journalist and a single mother. She unknowingly risks her son and his father’s lives by showing them a cursed videotape. A

critic noted:

“If she had never entered the public sphere and viewed the cassette in the first place, she would not have inadvertently caused Noah’s death, nor would she have to potentially cause the death of another. Rachel would, perhaps, have been better off staying at home.”

In her investigation into the video, she discovers the twisted, dark past of the video’s subject, Samara, a young girl who started life troubled (her birthmother tried to drown her). She was adopted by a couple, but her adoptive mother suffered from visions and haunting events due to Samara’s powers. They attempted to institutionalize Samara, but eventually the adoptive mother drowns her in a well after Samara cannot be cured of her psychosis. Her adoptive father, Rachel finds, locked Samara in an attic of their barn, and Samara left a clue of the well’s location behind wallpaper. (

Bitch Flicks ran an

excellent analysis of the yellow wallpaper and the themes of women’s stories in

The Ring.)

Samara’s life was punctuated by drowning, which has throughout history been a way for women to commit suicide or be killed (symbolizing both the suffocation of women’s roles and the return to the life-giving waters that women are often associated with). While Rachel “saves” Samara’s corpse and gives her a proper burial, Samara didn’t want that. She rejected Rachel’s motherhood and infects Rachel’s son. Rachel–in her attempts to mother–cannot seem to win.

|

| Rachel “saves” Samara from her watery grave, but she still cannot succeed. |

The ambiguous ending suggests that Rachel may indeed save her son, but will have to harm another to do so. This idea of motherly self-sacrifice portrays the one way that Rachel–single, working mother Rachel–can redeem herself. However, the parallel narrative of the dangers of silencing and “locking up” women is loud and clear.

And in 2009’s

Orphan, Esther is a violent, overtly sexual orphan from Russia who is adopted by an American family. Esther is “not nearly as innocent as she claims to be,” says the

IMDB description. This story certainly plays on the fear of the “other” in adopted little girls (much like

The Ring) and how that is realized in the mothers. In this film, Esther is actually an adult “trapped” in a child’s body. The clash of a childish yet adult female (as culturally, little girls are somehow expected to embody adult sexuality and yet be innocent and naïve) again reiterates this fear of little girls with unnatural and unnerving power. The drowning death of Esther, as her adoptive mother and sister flee, shows that Esther must be killed to be subdued. The power of mother is highlighted, yet the film still plays on cultural fears of mothering through international adoptions and the deep, disturbing duality of childhood and adulthood that girls are supposed to embody.

|

| Like Samara, Esther is a deeply disturbed daughter, capable of demonic violence. |

In the last 60 years, American culture has seen remarkable change and resistance to that change. Horror films–which portray the very core of society’s fears and anxieties–have reflected the fears of women’s social movements through the faces of terrifying little girls.

While nineteenth-century literature comforted audiences with the trope of a dead, beautiful woman, thus making her passive and frail (of course, we

still do this), twentieth and twenty-first century horror films force audiences to come face to face with murderous, demonic, murdered and psychotic little girls to parallel fears of women having economic, reproductive, parenting and marital (or single) power.

Little girls are supposed to be the epitome of all we hold dear–innocent, sweet, submissive and gentle. The Victorian Cult of

Girlhood and Womanhood bleeds into the twenty-first century anti-feminist movements, and these qualities are still revered.

Horror films hold a mirror up to these ideals, distorting the images and terrifying viewers in the process. The terror that society feels while looking at these little girls echoes the terror it feels when confronted with changing gender norms and female power.

—

Leigh Kolb is a composition, literature and journalism instructor at a community college in rural Missouri.