In films and TV male characers are usually the ones who get to have all the fun, especially when their characters commit crimes. Women characters aren’t allowed the relish many male characters take in stealing–and getting away with it. Though some exceptions to the rule exist–Bridget/Wendy in The Last Seduction and Melina Mercouri’s character in Topkapi–more often women play party-pooper roles like Jennifer Lopez in Out of Sight as the U.S. Marshall trying to capture George Clooney’s escaped, bon vivant bank robber.

The eponymous center of Kirk Marcolina and Matthew Pond’s documentary The Life and Crimes of Doris Payne (the opening night selection of the Roxbury International Film Festival) is an anomaly, a woman who steals and is not only unrepentant, but takes great pride in her skill. Doris is a slim, elegant, 80-something African American who has spent much of her life stealing jewelry, from a watch in the Jim Crow southern town where she grew up to top-price diamonds she accrued while staying in luxury hotels throughout Europe.

Part of Doris’s ability to steal undetected was, she explains, her creation of a persona, whether she played the “nurse” to a white accomplice or, while wearing impeccable clothes, she casually mentioned to the jewelry store staff the name of her famous (though not well known enough for anyone to know better) “husband.” We spend a lot of time hearing Doris’s stories and even see, when Doris meets with a jewelry store proprietor (who shares Doris’s obsession with gems: they seem to get along well), a security officer approach her to tell her that she can’t be in the store because of outstanding charges against her. She tells him that she didn’t know the restrictions applied to the whole mall and not just Macy’s and she leaves without an argument, explaining politely and meekly to him that she knows he’s just doing his job. Later she tells us, in a very different tone and stance, that she knew the best way to play the situation was to show the guard more respect than he deserved. As we hear from an academic, “Doris Payne for me is someone who manipulates people. I mean, that’s her job.”

Doris’s stories become more far-fetched: in Switzerland she sews a diamond into her girdle, dropping the setting into the sea, and later escapes “through cornfields” after she is taken to a hospital, eventually catching a cab to the airport where she boards a plane out of the country. So we begin to wonder whether she is playing us the same way she played the guard (though one of the directors confirmed in the Q and A afterward that records show Doris was indeed arrested in Switzerland–and did escape). The screenwriter who adapted Doris’s life story into a script (optioned by Halle Berry but progress on production seems to have stalled) says, “Doris is the protagonist and the antagonist in the screenplay Doris Payne writes herself every day.”

We also wonder about the current charges against her. Doris has an excellent lawyer (whom the co-director explained in the Q and A, ended up working pro bono for Doris, which wasn’t the lawyer’s original intention) who exploits every angle to make the jury doubt Doris’s guilt. Doris herself interjects “facts” about the main witness/clerk’s testimony which make us think her identification of Doris is erroneous. With people of color more likely to be accused of stealing and white people (like the witness) more likely than people of color to mistake one Black woman for another, we go back and forth on ascertaining Doris’s guilt even as we see (or don’t see) her steal a ring in front of the camera, while she talks to an outdoor jewelry vendor with her friend from childhood, Jean.

Is Doris, like some older shoplifters, addicted to the thrill of stealing? We see, that, in spite of her expensive-looking clothes she shares a room–and a small closet–with another woman in a halfway house. So does she steal because she has no other means of support? The co-director mentioned during the Q and A that because Doris has spent her life as a jewel thief, she doesn’t have Social Security–and the estimated 2 million dollars worth of jewels she has stolen isn’t much when divided over her career of 60 years. Doris also takes obvious pleasure in recounting her adventures, so excitement and money are probably both factors in her continuing to steal.

The prosecutor at her trial says, “She has made a lifelong career out of stealing and taking advantage of people.” As the judge at the end wonders what to do with her, so do we. Prison seems even more of a waste of resources for Doris than it does for other nonviolent criminals: it doesn’t deter her (she has been imprisoned before, including the time when her white ex-boyfriend/accomplice turned her in as part of a plea deal) and because of her advanced age, even a truncated sentence could mean that she would die behind bars. The filmmakers, with their clumsy reenactments, don’t seem quite up to dissecting the complexities that Doris’s life presents, but we still think about them, even after the movie is over.

[youtube_sc url=”http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WQ5Cwax-aik”]

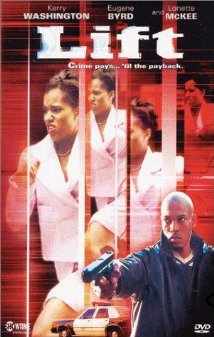

Lift, the closing selection from the festival, is a film which the festival originally premiered in 2001, when the star, Kerry Washington, was largely unknown. The movie, filmed on location in Boston and Roxbury offers a fictional counterpoint to Doris Payne. The protagonist, Niecy (Washington) is a chic window-dresser, who uses wire cutters, a big, bulky sweater and fake credit cards and identities to shoplift expensive designer clothing, which she either sells to people she knows in her neighborhood or keeps for herself or her family.

Washington isn’t quite the actress here that she was in the excellent Our Song (released shortly before Lift started filming), and the script by co-directors DeMane Davis and Khari Streeter has a muddled and clichéd it’s-all-Mom’s-fault subplot about Niecy’s relationship with her mother (Lonette McKee), but the scenes of Niecy trying to navigate between her criminal, personal, and family lives present questions that don’t have easy answers. Her extended family know (like everyone else in the neighborhood) that she steals, but are (except for her mother) glad for her gifts–since, except for her mother, they don’t have much money themselves. They also enjoy her company: we rarely see in films criminals who are “good” or even “normal” people when they aren’t breaking the law.

But unlike in Doris Payne, we see that Niecy’s “victimless” crimes do have consequences. Greed, revenge, and a distaste for leaving witnesses behind means people get hurt, and although Niecy isn’t directly responsible, she’s not blameless either. In spite of a “silver lining” ending that seems tacked on, when Niecy finally decides to stop stealing, she does so too late–for herself and for her loved ones.

___________________________________________________

Ren Jender is a queer writer-performer/producer putting a film together. Her writing besides appearing every week on Bitch Flicks has appeared in The Toast, xoJane and the Feminist Wire. You can follow her on Twitter @renjender.