|

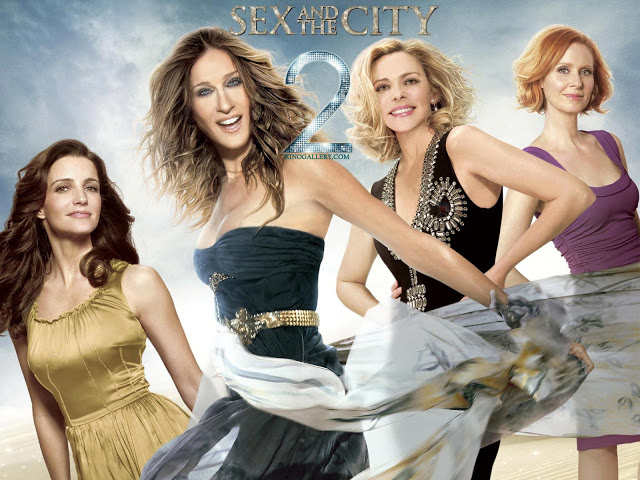

| The story of Carrie, Miranda, Charlotte, and Samantha continued in Sex and the City 2 (2010) |

This is a guest post by Emily Contois.

I’m not embarrassed to admit it. I totally own the complete series of Sex and the City—the copious collection of DVDs nestled inside a bright pink binder-of-sorts, soft and textured to the touch. In college, I forged real-life friendships over watching episodes of the show, giggling together on the floor of dorm rooms and tiny apartments. Through years of watching these episodes over and over again, and as sad as it may sound, I came to view Carrie, Miranda, Charlotte, and Samantha like friends—not really real, but only a click of the play button away.

On opening night in a packed theater house with two of my friends, I went to see the first Sex and the City movie in 2008. Was the story perfect? No. But it effectively and enjoyably continued the story arc of these four friends, and it made some sort of sense. Fast forward to 2010 when Sex and the City 2 came to theaters. I had seen the trailer. I’ll admit, I was a bit bemused. The girls are going to Abu Dhabi? Um, okay. Sex and the City had taken us to international locales before. In the final season, Carrie joins Petrovsky in Paris and in this land of mythical romance, Mr. Big finds her and sets everything right. When their wedding goes awry in the first movie, the girls jet to Mexico, taking Carrie and Big’s honeymoon as a female foursome. But the vast majority of this story takes place in New York City. It’s called Sex and the City. The city is not only a setting, but also a character unto itself and plays a major role in the narrative. So, it seemed a little odd that the majority of the second movie would take place on the sands of Abu Dhabi.

|

| In Sex and the City 2, the leading ladies travel to Abu Dhabi |

Before the girls settle in to those first-class suites on the flight to the United Arab Emirates, however, we as viewers must suffer through Stanford and Anthony’s wedding. From these opening scenes, there’s no question why this dismal film swept the 2011 Razzie Awards, where the four leading ladies shared the Worst Actress Award and the Worst Screen Ensemble. How did this happen?? These four ladies were once believable to fans as soul mates—four women sharing a friendship closer than a marriage. And yet they end up in these opening scenes interacting like a blind group date—awkward, forced, and cringe-worthy.

From the moment our Sex and the City stars have decided to take this trip together, however, Abu Dhabi is viewed through a lens of Orientalism, demonstrating a Western patronization of the Middle East. Starting on the first day in the city, Abu Dhabi is framed derisively as the polar opposite of sexy and modern New York City. It’s also stereotypically portrayed as the world of Disney’s Jasmine and Aladdin, magic carpets, camels, and desert dunes—”but with cocktails,” Carrie adds. This borderline racist trope plays out vividly through the women’s vacation attire of patterned head wraps, flowing skirts, and breezy cropped pants. Take for example their over-the-top fashion statement as they explore the desert on camelback, only after they have dramatically walked across the sand directly toward the camera of course.

|

| Samantha, Charlotte, Carrie, and Miranda explore the desert, dressed in a ridiculous ode to the Middle East via fashion |

The exotic is also framed as dangerous and tempting, embodied in Aidan, Carrie’s once fiancé, who sweeps her off her feet in Abu Dhabi and nearly derails her fidelity. This plays out metaphorically as they meet at Aidan’s hotel, both of them dressed in black and cloaked in the dim lighting of the restaurant.

|

| Carrie “plays with fire” when she meets old flam, Aidan, for dinner in Abu Dhabi |

Sex and the City 2 also comments upon gender roles and sex in the Middle East. For example, in a nightclub full of belly dancers and karaoke, our New Yorkers choose to sing “I Am Woman,” a tune that served as a theme song of sorts for second wave feminism. As our once fab four belt out the lyrics, young Arabic women sing along as well. And yet the main tenant of the film appears to be an ode to perceived sexual repression rather than women’s rights.

|

| The ladies of Sex and the City 2 sing “I Am Woman” at karaoke in an Abu Dhabi nightclut |

Abu Dhabi is a place where these four women—defined in American culture not only by their longstanding friendship, but also by their bodies, fashionable wardrobes, and sexual exploits—must tone it down a bit. For example, Miranda reads from a guidebook that women are required to dress in a way that doesn’t attract sexual attention. Instead of providing any context in which to understand the customs of another culture, Samantha instead repeatedly whines about having to cover up her body. Our four Americans watch a Muslim woman eating fries while wearing a veil over her face, as if observing an animal in a zoo. The girls poke fun at the women floating in the hotel pool covered from head to ankle in burkinins, which Carrie jokingly comments are for sale in the hotel gift shop. In this way, Arab culture is both commodified and ridiculed. And rather than finding a place of common understanding, the American characters are only able to relate to Arab women by finding them to be exactly like them, secretly wearing couture beneath their burkas. While fashion is the common thread linking these American and Arab women, the four leading ladies don’t really come to understand the role and meaning of the burka. Instead, after Samantha causes a raucous in the market, the girls don burkas as a comedic disguise in order to escape.

At this point in the film, the main narrative conflict is again a very white problem—if the ladies are late to the airport, they’ll (gasp!) be bumped from first class. Struggling to get a cab to stop and pick them up, the women have to get creative. In a bizarre twist that references a scene from the first twenty minutes of the film, Carrie hails a cab by exposing her leg, as made famous in the classic film, It Happened One Night. While she gets a cab to stop, one is struck by the inconsistency. The women were just run out of town for Samantha’s overt sexuality and yet exposing a culturally forbidden view of a woman’s leg is what saves the day? Or is the moral of the story that a car will always stop for a sexy woman, irrespective of culture? Either way, our leading ladies make it to the airport, fly home in first-class luxury, and arrive home to better appreciate their lives. No real conflict has been resolved—though a 60-second montage provides sound bites of what each character has learned.

|

| In homage to It Happened One Night, Carrie bares her leg to get a cab to stop in Abu Dhabi |

Throughout the course of Sex and the City 2, the United Arab Emirates doesn’t fair well, but neither does the United States, as the land of the free and home of the brave is reduced to a place where Samantha Jones can have sex in public without getting arrested. Sex and the City 2 stands out as a horrendous example of American entitlement abroad, a terrible travel flick, and a truly saddening chapter for those of us who actually liked Sex and the City up to this point.

Emily Contois works in the field of worksite wellness and is a graduate student in the MLA in Gastronomy Program at Boston University that was founded by Julia Child and Jacques Pépin. She is currently researching the marketing of diet programs to men and blogs on food studies, nutrition, and public health at emilycontois.com.