This is a guest post by Deborah Riley Draper.

Fortunately I have the honor and privilege of preserving and elevating the historical contributions of people of color everyday. But, since it is Black History Month, I would be remised if I didn’t take this opportunity to highlight some of the original baddass chicks of cinema. Contrary to the misconceptions and blatant neglect of historical fact, Black women have enjoyed success and failure in the movie-making business since the industry began practically. And not too unlike today, these trailblazers of the Silent Movie Era operated fully and completely outside of the Hollywood or the burgeoning Hollywood system.

Of course, most people are familiar with Zora Neale Hurston and her books because Halle Berry starred in the 2005 TV movie adaptation of Their Eyes Were Watching God produced by Oprah Winfrey. The Harlem Renaissance bad girl was not only a celebrated novelist and playwright but a noted anthropologist as well. She produced ethnographic films in 1928 capturing the lives, customs, and beliefs of Southern people. If you are ever in the Library of Congress, be sure to check Hurston’s filmography.

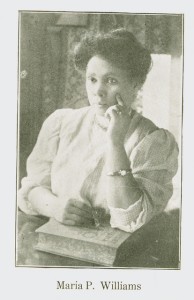

Seven years before Hurston’s films and exactly 100 years before #OscarsSoWhite was trending, the legendary Black newspaper The Chicago Defender mentioned the “three-reel drama” Shadowed by the Devil, penned and produced by Mrs. Miles Webb, in their section “Among the Movies.” Around the same time, photographer Jane Louise VanDerZee Toussaint Welcome, personal photographer of Booker T. Washington and sister of famed Harlem photographer James VanDerZee, and her husband Ernest Toussaint Welcome opened The Toussaint Motion Picture Exchange. Jennie directed Doing their Bit, a short detailing the efforts of Blacks in the military during WWI. Another film pioneer, Maria P. Williams, produced, distributed, and acted in her own film, The Flames of Wrath (1923) and the Norfolk Journal and Guide printed, “Kansas City is claiming the honor of having the first colored woman film producer in the United States.” And Williams’ best friend, Tressie Souders was lauded by the Black press as the first African American woman director for her film, A Woman’s Error (1922), which was distributed by the Afro-American Film Exhibitors’ Company based in Kansas City, Mo. These woman ignored stereotypes, Jim Crow laws, and the lack of women’s rights to get behind camera to capture and document important stories. They used a pen and a camera to create important pathways and springboards to fuel the march to equality.

It is important to mention, since we are talking about woman who used film to impact the social consciousness of a very racially oppressive society, the writer Drusilla Dunjee Houston. She wrote the screenplay, “Spirit of the South: The Maddened Mob,” one of earliest African-American responses to Thomas Dixon and D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915). She was unable to get it financed and produced.

Black women have been involved in every aspect of film from the beginning. While Oscar Micheaux is regarded as the father of Black independent cinema, we must also applaud the women who stepped out prior to men and women of all races to create jobs, opportunities and provide authentic depictions of them on the screen. These woman found their own spark and seed money to create a lane, a voice and compelling narratives that would accurately depict African American life and inspire the next generation. They pioneered cinematic techniques and introduced ways to flourish outside of Hollywood. They were entrepreneurs with start-up film companies. Maybe one day, they will trend on twitter or receive posthumous recognition for their contributions. But they did not do it for fame or hardware, they saw a new industry that they could use to instill pride and confidence in their community and propel the race forward. So for this Black History Month, we can proudly say #EarlyCinemaSoBlack.

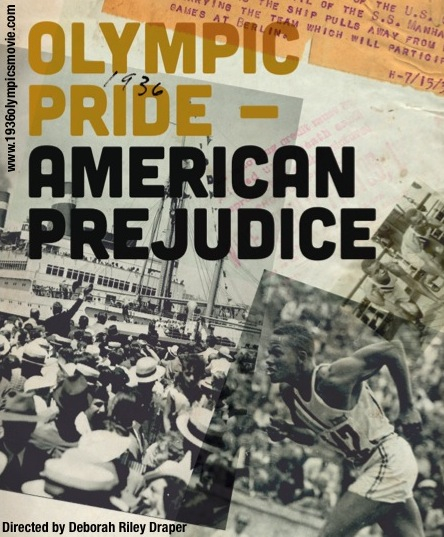

Though not cinematic pioneers, two historically significant women will be featured in the upcoming documentary Olympic Pride, American Prejudice. The film captures the heroic turn of 18 African American athletes who defied racism on both sides of the Atlantic to complete in the 1936 Olympics. And, Louise Stokes and Tydie Pickett, the first Black women ever selected to an American Olympic team, bravely and proudly stepped onto the U.S.S. Manhattan to represent the U.S. almost 30 years prior to the Civil Rights Bill. This film is currently funding on Seed&Spark. Please support the telling of this significant chapter in American history and a precursor in the modern Civil Rights movement. Click here to contribute or log on to www.1936olympicsmovie.com to learn more.

See also at Bitch Flicks: Forgotten Great Black Actresses: “Race Films” in Early Hollywood and Through a Lens Darkly: Toward a More Beautiful Family Album

___________________________________

Filmmaker Deborah Riley Draper has a proven track record for creating compelling brand stories as an advertising agency executive. Draperʼs first documentary, Versailles ʼ73: American Runway Revolution, brought to life the legendary 1973 fashion battle between five French and five American designers. Versailles ʼ73 has screened all over the world and received acclaim from critics and fans alike, including the New York Times, LA Times and Harperʼs Bazaar. The film was selected to the St. Louis International Film Festival, NY Winter Film Awards, John Hopkins Film Festival, Marthaʼs Vineyards African American Film Festival, Denver Film Society Winter DocNights, and Gateway Documentary Festival as well as selected to screen at fashion and design festivals in Canada, Saudi Arabia, Croatia, Estonia and Australia. Versailles ʼ73 is distributed through Cinetic/Filmbuff on VOD in North America, Europe and Australia. The documentary has also been optioned for development into a feature film.

Draper is currently completing production on Olympic Pride, American Prejudice, the story of the 18 African American athletes of the 1936 Summer Olympic Games. She is also completing two feature film scripts. Draper recently contributed to several museum projects, including The Groninger Museum in The Netherlands exhibition on Marga Weiman, Museum of the City of New Yorkʼs Stephen Burrows: When Fashion Danced and the Andre Leon Tallyʼs An American Master of Inventive Design at SCAD. Draper will be a contributing writer to the Fall 2015 NKA: Journal of Contemporary African Art Fashion Edition.

Draper has been making long format content and commercials for more than 15 years for clients such as Coca-Cola Classic, Sprite, The Georgia Lottery Corporation, Blue Cross-Blue Shield, ExxonMobil, Fedex, Bayer CropScience and HP. She is currently the Client Service Director at Iris Worldwide. Prior to iris, Draper spent eight years at BBDO and three years at the Publicis network agency Burrell Communications Group. Her advertising work has won two Regional Emmy Awards, Gold Effie, and numerous Addys.

The avid Florida State University Seminole is frequent lecturer for the AAAA Advertising Institute and a 2014 Distinquished Visiting Professor at Johnson & Wales University, Florida Campus.