Written by Max Thornton.

The relationship between Christianity and disability is complex and many-sided, encompassing stigma and pity, aid and condescension, systematic exclusion and the creation of refuge spaces – and it’s not just an academic concern for scholars of religion. Societies that took shape under the influence of western Christianity still reflect and perpetuate Christian philosophical and ethical ideas, both in cultural attitudes and in policy and law. Disability is no exception. Levitical purity codes, New Testament healing narratives, and Augustinian theology of original sin all contribute to the mishmash of ableism that pervades twenty-first century US culture.

Disability scholars and cultural critics are doing some terrific work to examine and dismantle ableism. Some of my favorites include Andrew Pulrang at Disability Thinking (and his podcast, Disability.TV), the Disability Visibility Project, and the BBC’s Ouch podcast. You don’t have to spend long reading disability criticism to learn that one of the most hated forms of disability representation in popular culture is inspiration porn. The late, wonderful, deeply mourned Stella Young put it like this:

“[In inspiration porn] we’re objectifying disabled people for the benefit of nondisabled people. The purpose of these images is to inspire you, to motivate you, so that we can look at them and think, ‘Well, however bad my life is, it could be worse. I could be that person.’ But what if you are that person?”

Hollywood in particular loves inspiration porn, to that point that watching a movie about a disabled person is a source of dread for anyone who cares about disability studies. Will the disabled person be a precious angel, too good for this sinful earth? Will they exist primarily to teach the non-disabled protagonist a lesson? Will they be a bitter cripple who gradually triumphs over this dreadful tragedy? Will I throw up in my mouth?

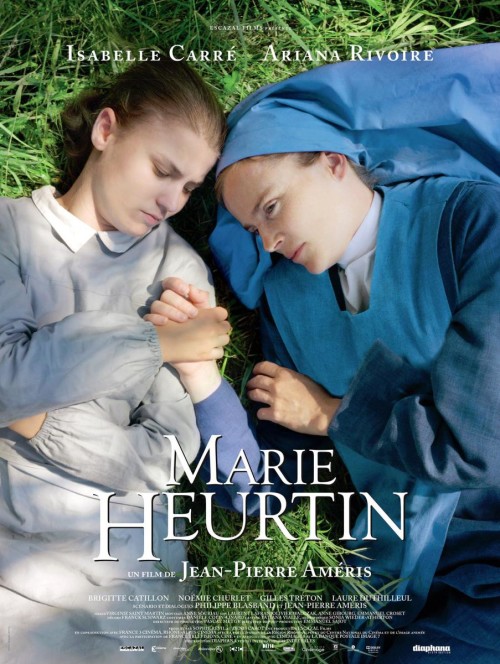

I approached Marie’s Story with less trepidation than usual, though, both because it’s a small French film rather than slushy Oscar-bait, and because the titular Marie is played by a Deaf actress, the talented young Ariana Rivoire. For the most part, thankfully, my confidence was well-placed.

Marie’s Story dramatizes the real-life biography of Marie Heurtin, a deafblind girl who was taken in by a convent in the late nineteenth century. The convent educated deaf children, but felt ill-equipped to teach a deafblind child who had no communication skills – until one very determined nun, Sister Marguerite, insisted on giving Marie a chance.

So far, so Miracle Worker, and in the early stages the film certainly hits a lot of beats familiar from popular narratives of Helen Keller’s life: the terrible fights with the strong-willed mentor, the transformation from wildling to neatly-coiffed well-mannered young woman, the come-to-Jesus moment of language comprehension. What’s distinctive about Marie’s Story is its convent setting and the normalization of the deaf environment (how many movies have you seen that pass the Bechdel Test in sign language as well as spoken words?).

Wisely, given popular Christianity’s reprehensible enthusiasm for the doubly nauseating Inspiration Porn With Added Jesus, Marie’s Story treads lightly around the religion aspect. No miracle healings or trite theodicies here – the most explicitly theological sequence in the film is a conversation around mortality, when Marie asks in frustration: “Who is God? Where is he? I can’t touch him.” The film as a whole functions as a panentheistic affirmation that she absolutely can touch God: despite Christianity’s emphasis on sight and sound as the primary senses for divine encounter, Marie’s alternative embodiment is the locus for divine encounter through touch and scent. From the opening sequence, in which Sister Marguerite climbs a tree and, looking for all the world like The Creation of Adam, extends a hand to a frightened Marie, this film stresses the power of bodily touch.

The film doesn’t entirely escape certain inspiration porn pitfalls, primarily in voiceovers of Sister Marguerite’s diary entries where she gushes about how much she’s learned from Marie and describes Marie’s transformation in weird racialized and colonial terms of “savagery” and “imprisonment.” However, Marguerite’s own chronic illness keeps the relationship from being too one-sided. It’s in the final third that the film really shines, as Marie develops agency and character of her own, even tending to Marguerite just as the nun had previously cared for her. In perhaps the most moving sequence, Marie teaches her parents how to greet her in sign language, with Marguerite translating and facilitating but never speaking for or over Marie.

Ultimately, this is not a film about Saint Sister Marguerite and her noble civilizing mission to help a poor deafblind girl. Instead, it’s an intimate portrayal of an unusual relationship between two young women (watch for a scene where they lie in a meadow together like Bella and Edward), a quietly beautiful story of faith and female friendship.

Max Thornton blogs at Gay Christian Geek, tumbles as trans substantial, and tweets at @RainicornMax. He studies theology, disability, and gender, and gets really excited when they all come together.