This is a guest post by Rosa Rodriguez.

I am sure you have heard the terms “lead” and “character” actor/actress. The lead actor/actress is the one who plays the role of the protagonist of a film or show. The character actor/actress plays the sidekick, the friend, the co-worker, the villain, and the minor roles.

Lead actors are usually “attractive” by general, narrow standards: thin, slim, muscular; clear skin and flawless hair and makeup; generally tall and able bodied. They are normally white or, if they have “the right look,” sometimes of other ethnicities. They are young, or youthful. They are normally cisgender and straight. They are the big names that most of us remember.

[youtube_sc url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FSwhRZwFjfY”]

A funny parody to Lorde’s “Royals” that definitely strikes a chord.

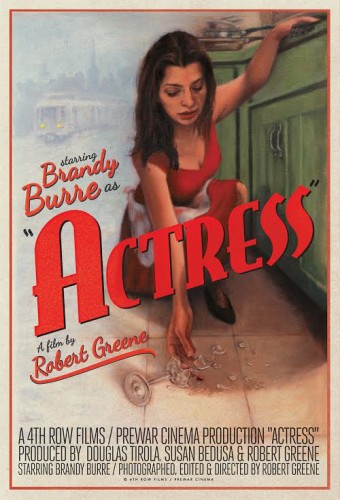

The character actors are more “unconventional-looking”: short, very tall, bald or balding, stocky, heavy set. They have the crooked noses or teeth, the big ears. They are the people of ethnicities other than white and oftentimes perform with an accent or a speech impediment. They are the middle aged and older guys and gals. They are the gay, transgender, gender fluid, etc. They are usually better known as “Whatshername” or “That guy from that thing” (check out a post on this blog called “Whatshername as a Great Actress: A Celebration of Character Actresses” for a beautiful explanation of what a character actress is and some interesting comparisons to the male counterpart).

These standards are widely spread on mainstream TV and movies, and generally accepted both by audiences and by actors and actresses, who want to be able to work and make a living. We are used to seeing the “attractive” people as the center of the stories. The belief is that the lead actors/actresses have the physical beauty and magnetism “needed” to play love interests and heroes, with whom the general population is meant to identify. The character actors fill the world around these main characters. Some of these supporting roles are quite strong and interesting, but they exist in relation to the leads. They are secondary characters.

A lot of character actors and actresses have managed to have long, successful careers playing supporting roles, and sometimes an offbeat lead here and there. It can be quite fulfilling to play a character with real, human flaws (other than the muted ones usually allowed to the leads, such as clumsiness, shyness, or naïveté). Even when said characters are underwritten, or do not appear in the film or show long enough, it can be very satisfying for the performer and the audience when these brief appearances show interesting, real human beings.

The problem I see with the accepted standards is that in real life every single person is the lead character of his or her particular story. We all have lives, passions, dreams, pursue careers and occupations, fall in love, have our hearts broken. All of us, the thin, the medium sized, the large, the blond, the brunette, the red-head, the bald, the balding, the young, the old, the loud, the quiet, the Hispanic, the Asian, the Middle Eastern, and so on, have goals and aspirations, battles, successes, loses. We all teach and learn lessons in life.

[youtube_sc url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QTCHzcsxrdg”]

A message to Hollywood from a few well-known character actors. Funny and true.

Why, then, are most mainstream movies and TV shows out there representing a world that does not seem to match the real world in which we live? And most importantly, why do we accept that as normal? Why do we buy it? Specially knowing that what we see in movies and on TV, whether we want it or not, shapes our minds and the way we behave and perceive reality. It shapes society as a whole.

I find myself wanting more than what I am seeing. I want to see more movies and TV shows display a society where people of all looks, sounds, backgrounds, get to lead their own stories. I want to see a story about a Latina with an accent who is a college professor or a scientist. I want to see a story about a short guy with a receding hairline finding the love of his life. I want to see a love story between two senior citizens that is not meant to be a joke. I want to see main characters with some acne, or an apple shaped body, or frizzy hair. I want the full-fledged characters who look like everyday people to be the leads of stories, just like they are in real life. I believe if the audiences demanded more of that, it would be made.

I am a founding member of a production company called Room 1209 Productions, together with Ravin Patterson, John Wiggins, and Patrick Avella. We define as our mission to generate opportunity for ourselves and our fellow actors, writers, directors, and other artists, through the creation of challenging, imaginative, quality content that represents the diversity found in real life.

Our first project is called Space Available, a character-driven web-series about a film student shooting a documentary in his seedy stepfather’s rehearsal studio, in an effort to expose the underground world he suspects exists behind the artistic façade. This is a project about people, about duality and gray areas.

So far we have been able to finish and release a prologue and two episodes, and are in the midst of a crowdfunding campaign, through Seed & Spark, to fund four more episodes that will complete season one. We have a myriad of characters of all colors, sizes, shapes, and backgrounds in the works, and are proudly committed to creating a space for character actors to take the lead in interesting stories. Should we have the opportunity to finish the first season of this project and move on to others, there will be a rich and diverse lineup of writers, directors, and other artists, that will get to work and tell their stories (to learn more about Space Available, and to view the prologue and first two episodes, visit our website at www.SpaceAvailableSeries.com, and our Seed & Spark campaign page at: http://www.seedandspark.com/studio/space-available-web-series)

Rosa Rodriguez is an actress, singer, writer and producer living in LIC, New York. She was born and raised in the Dominican Republic and is proud of her roots and her accent. She has numerous stage performances, short films, commercials, and industrials to her credit. She also holds a degree in Civil Engineering, and earned her Master’s in Construction Management from NYU. For more about Rosa visit her website: RosaRodriguezNYC.com.

[youtube_sc url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WACRJdl9qVg”]