|

| Marion Cotillard and Owen Wilson in ‘Midnight in Paris’ |

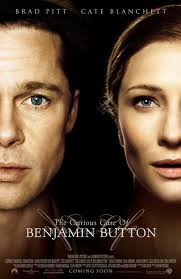

In Allen’s latest Oscar-nominated endeavor, Midnight in Paris, Gil Pender (Owen Wilson) is a successful Hollywood screenwriter struggling to write his first novel. He visits Paris with his constantly complaining fiancé Inez (Rachel McAdams), as he yearns to live amongst his literary idols in the Roaring Twenties. Gil discovers that at midnight, he is able to transport to 1920s Paris and hobnob with writers, musicians and painters. A love letter to Paris and artists, Midnight in Paris explores the dichotomy between illusions of nostalgia and pragmatically embracing the present.

Allen has a knack for evoking the visceral beauty of a city: NYC in Annie Hall and Manhattan, Barcelona in Vicky Cristina Barcelona, Paris in Midnight in Paris. With lush cinematography, Allen capturesthe seductive allure and breathtaking romance of Paris. He also infuses the film with myriad authors and artists from the 1920s, a bibliophile’s dream. These delightful distractions almost made me forget (almost) that while an okay film, it’s certainly not a great one.

Now, I didn’t hate Midnight in Paris like my kick-ass colleague Stephanie. But I totally understand why she did because it royally pissed me off too. The portrayal of women in this film is fucking problematic.

Kathy Bates is fantastic as writer and art collector Gertrude Stein. Yet she’s highly underutilized, striving to make the most of her small role. Incredibly influential, we witness Stein’s Parisian salon which attracted talented writers, like Ernest Hemingway and Ezra Pound, whom she advised and mentored. After reviewing his manuscript, Gertrude bestows Gil with her wisdom: “We all fear death and question our place in the word. The artist’s job is not to succumb to despair but to find an antidote for the emptiness of existence.” Aside from Gertrude, none of the female characters are either truly likeable, interesting or complex individuals.

Audacious Zelda Fitzgerald (Alison Pill, who tries her best to imbue her with charm), F. Scott Fitzgerald (Tom Hiddleston)’s wife and a writer in her own right, diminishes her artistic talent by saying, “…and I realize I’ll never write a great lyric and my talent really lies in drinking.”

An “art groupie” muse, Adriana (Marion Cotillard) designs couture fashion and becomes the object of Gil’s affection, despite his fiancé. When Gertrude reads the first line of Gil’s book aloud, Adriana praises it saying she’s “hooked” and later calls his musings on the “City of Light” poetic. Enamored with her, they begin to spend their evenings talking and walking around Paris. Cotillard is a divine actor. But her character is beige and boring. Although I must admit I’m glad Adriana ultimately chooses her own path.

In addition to seeking Stein’s advice on his book, Gil turns to another woman, an art museum guide (Carla Bruni), for advice on being in love with two women at the same time. Oh, and he also flirts with 25-year-old Gabrielle (Léa Seydoux) (cause you know, that’s what middle-aged dudes do) who sells old records from the Jazz Age and shares his love of Paris in the rain.

|

| Owen Wilson and Rachel McAdams in ‘Midnight in Paris’ |

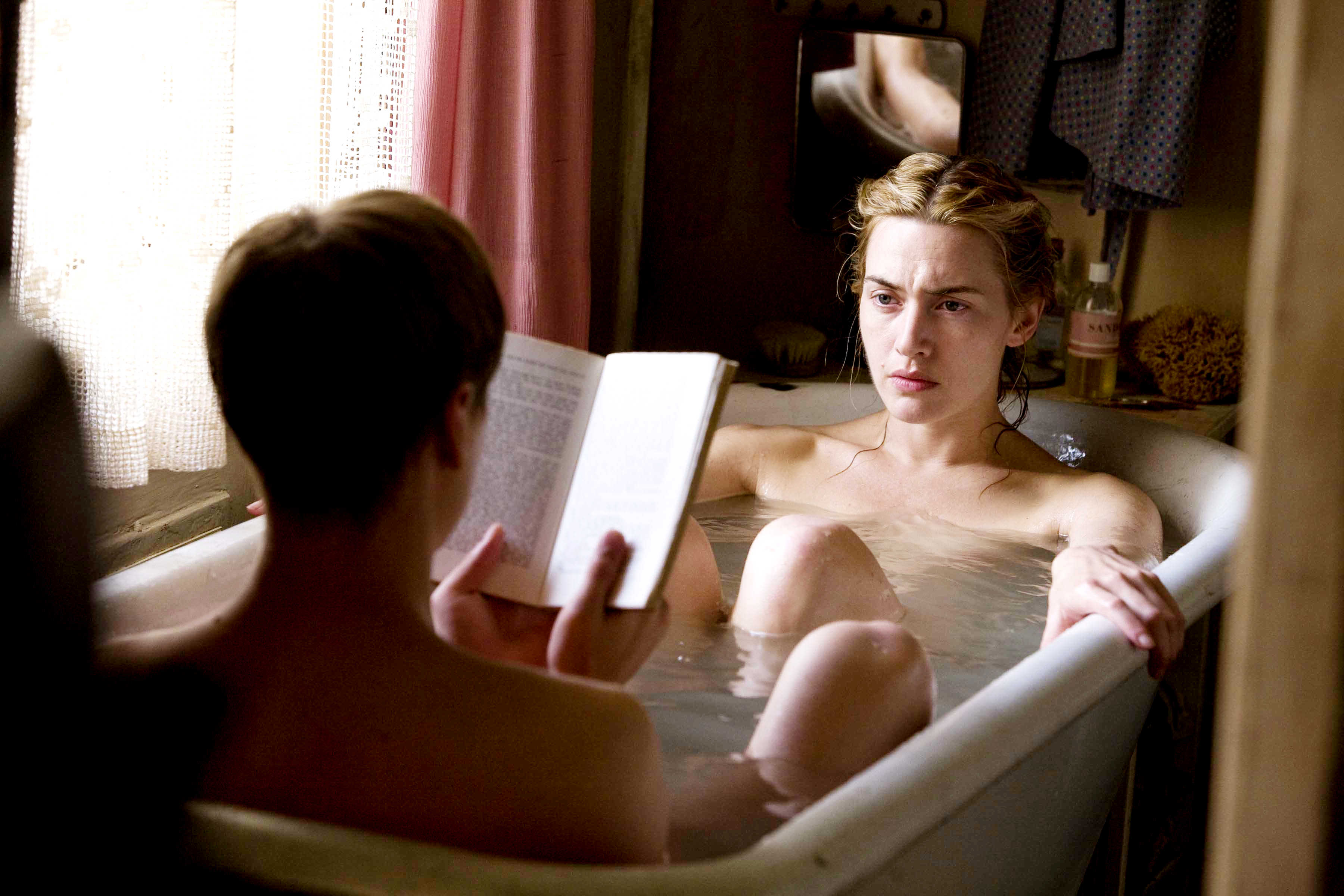

Now, I don’t automatically have a problem with a villainous or unlikeable female character, especially since there are so many female roles in the film. In fact, I often lament how unlike men, women are not allowed to play unlikeable or unsympathetic characters. But I have a huge problem with the “nag” role. The cliché of women as “nags” permeates pop culture.

I also have a huge problem that the seemingly sole reason Inez was made so horribly despicable was to “allow” Gil to cheat on his fiancé. The audience would sympathize with Gil for kissing another woman, buying her trinkets, baring his soul to her and planning to sleep with her even though he was engaged because his fiancé was such a shrew. Oh that’s right, I forgot! It’s okay to cheat on someone as long as they’re an asshole.

Allen told Rachel McAdams that she should play this role as she should “want to play some bitchy parts” as they’re more interesting. Maybe. But not this part. I didn’t find her character interesting at all. Yes, McAdams tries her best with the material she’s given. But the character is one-dimensional and annoying, lacking any depth or complexity.

Midnight in Paris, like pretty much all of Allen’s films, lacks diversity. They’re a sea of white with no people of color anywhere in sight. Oh I take that back. There’s a black woman in a car that Gil gets in on his “way” to the 1920s, one shot of Josephine Baker (Sonia Rolland) dancing that lasts all of 30 seconds and a few black people watching her dance.

Along with race, sexual identities are also omitted. The film contains three famous lesbians: Gertrude Stein, Stein’s life partner Alice B. Toklas (Thérèse Bourou-Rubinsztein) and writer Djuna Barnes (Emmanuelle Uzan). Of all three, Gil only alludes to Djuna’s sexuality when he says she led when they danced together. So lesbianism is almost completely erased, paving the way for good ole’ heteronormativity.

The only overt gender commentary occurs when Ernest Hemingway (Corey Stoll) says, “Pablo Picasso thinks women are only to sleep with or to paint,” but he believes “a woman is equal to a man in courage.” Which is interesting since Allen is a person who in his personal life doesn’t always believe equality in relationships is desirable: “Sometimes equality in a relationship is great, sometimes inequality makes it work.” (???) Yeah, this explains a lot. He also has a penchant for younger women, in his movies and in reality, because younger women are more innocent, “before they get spoiled by the world.” Gag.

I swear people nominated Midnight in Paris for so many awards because Hollywood is lazy. Rather than nominating ground-breaking, intelligent films like Pariah, The Whistleblower or Young Adult, this gets nominated because Allen is a famous, old, white male director. Good job, Hollywood. Way to keep perpetuating the dude machine.

The film suffers from a major woman problem. The women in the film are just as intelligent and talented as their male contemporaries. Gil turns to women for advice and guidance. Yet Allen reduces almost all of them to love interests and arm candy, nothing more than satellites to a dude.