Imagine you walk into your home. An eviction notice awaits you. The government demands you relocate in order to dig up your land. If you choose not to leave, you receive death threats. This is the reality many Colombian civilians face. While a notorious drug war has been waged, another war ravages the South American country’s land and its people. I had never known about this struggle.

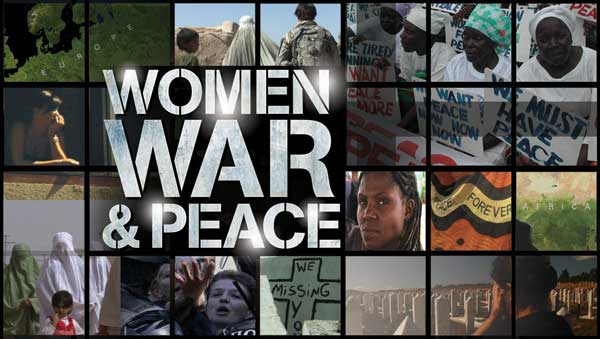

In The War We Are Living, Part 4 of Women, War and Peace (WWP), Colombian women grapple with displacement as their country is torn apart. Co-written by Oriana Zill de Granados and Pamela Hogan, WWP co-founder and executive producer, the chilling yet inspiring documentary is narrated by actor Alfre Woodard. Fueled by greed and a gold rush, guerillas and paramilitaries destroy homes and ravage bio-diverse lands. The government remains silent, failing to protect its citizens. Amidst this chaos, two female community leaders and activists, Clemencia Carabali and Francia Marquez Minas, admirably fight to hold onto their homes and save their land.

Beginning as a class struggle between the rich and poor, civil war erupted in Colombia. 40 years ago, armed guerillas fought for the poor, seizing land and attacking the government. Wealthy landowners created private militias, or paramilitaries, to protect them. Both the guerillas and paramilitaries funded their war through cocaine trafficking. “By the 90s, the guerillas and paramilitaries had turned Colombia into the most violent country in the Americas. Civilians were caught in the crossfire.”

After Alvaro Uribe was elected president, he “doubled the military,” “cracked down” on guerillas and forced “30,000 paramilitaries to turn in their guns.” Colombia pushed tourism to change the country’s notoriously dangerous image and garner income. “But today, there are two Colombias.” Claiming the paramilitaries demobilized, President Uribe declared the war over. And for wealthy urban residents, it was. But for the Afro-Colombian and Indigenous communities living in the rural Cauca Department, or municipality, the war rages on.

One of the most bio-diverse regions on the planet, Cauca’s land yields vast deposits of gold. Multinationals and paramilitaries force civilians off the land to excavate natural resources. Cauca is also home to over a quarter of a million Afro-Colombians. The land’s lucrative diversity has endangered the Afro-Colombian population. Civilians have faced massacres, kidnapping and continually receive death threats.

Human rights activist Clemencia Carabali has been forced to move 5 times due to displacement by armed paramilitaries. She belongs to the Municipal Association of Women (ASOM), a network of women’s groups. Carabali, who “wonders how she’s not dead,” found that “in war time, women could organize more freely than men:”

“In my zone there is a network of African women…When the paramilitaries take control of the territory, men are killed, accused of being guerillas so women develop a key role because they’re able to move around.”

Activist and community leader Francia Marquez Minas, also works closely with ASOM. She lives in La Toma, a mountain community of Afro-Colombians in Cauca who rely on mining to survive. But investors want to open large-scale industrial operations to extract the gold from La Toma, destroying the residents’ subsistence.

Marquez serves as Vice-President of La Toma’s community council, spearheading the fight to protect their land. Raising two sons, Marquez works in the mines part-time to put herself through college, not only to educate herself but to empower her community:

“So I told myself I have to study law because that gives you the tools to teach your community how to demand their rights.”

Carabali, Marquez and other community leaders organize to protest eviction. Colombian law states that permits to mine gold on Afro-Colombians’ land “requires consultation with their community councils.” But with a government plagued by corruption, numerous illegal permits exist. Hector Sarria, who received a license from the Institute of Geology and Mining (Ingeominas) 10 years ago to excavate La Toma’s gold, never met with La Toma’s council. But he claims his license states no Afro-Colombians live in La Toma. In March 2010, the court granted Sarria’s eviction request. Eviction would “uproot” 1300 families.

How can the government pretend no Afro-Colombians live in La Toma? How can they erase an entire ethnic community?? Carabali said:

“Colombia is one of the countries with the best laws to protect Afro-Colombians. Nevertheless those rights exist only on paper.”

Over the course of the last two decades, at least 16 million acres of land have been violently taken from Colombians. In the last 8 years, over 2 million have been displaced. Colombia has the second largest number of internally displaced people in the world after Sudan. With no jobs and contaminated water, displacement traumatizes civilians and rips families apart. Under international law, internally displaced citizens don’t receive the same protections that refugees do. Their government is supposed to address their rights. But in this case, how are Colombians supposed to obtain justice when their own government condemns them?

Afro-Colombians make up one quarter of Colombia’s population. In May 2010, coinciding with Afro-Colombian Day, which commemorates the end of slavery in Colombia, Sarria’s eviction was set to commence. People took to the streets, barricading the road to halt the eviction. Marquez said:

“The 21st is when we celebrate Afro-Colombianism in this country. The gift the government was giving us was a threat of eviction for our community. The message that is being relayed is that in this country the black communities don’t matter.”

In a meeting between community leaders and the Ministry of Mines, who issued Sarria his license, Marquez boldly declared:

“You cannot ignore us just because the government thinks more about the riches that can be extracted from this country, than it thinks about the lives of the people in this country…The community of La Toma will have to be dragged out dead. Otherwise we are not going to leave!”

In June 2010, the eviction was put on hold for political elections. Corruption plagues Colombia’s government. Former paramilitaries revealed ties to President Uribe and the Alto Naya Massacre (a 2001 killing spree in Cauca where paramilitaries dismembered and decapitated civilians with chainsaws and 4,000 survivors fled in terror). “1/3 of Congress was either in jail or under investigation for their links to the death squads.” Carabali insists that paramilitaries forced people to vote for Uribe, threatening them with death. Worried the rest of the world doesn’t know the truth, Carabali said:

“I get chills hearing all the positive things that are said about President Uribe. And I get chills because people don’t know all the damage he did especially to indigenous communities and black communities.”

The U.S. has given over $7 billion of assistance to Colombia. In order to continue receiving aid, Colombia must meet certain requirements, including military protection of the Afro-Colombian population. If human rights violations occur, foreign aid is supposed to stop. But the U.S. continues to provide funding, despite Colombia’s numerous human rights atrocities.

In September 2010, for the first time ever, the State Department, in its human rights report to Congress, highlighted La Toma’s land dispute in order to monitor the situation. It’s a step but the battle is far from over. Talking about the war she faces, Marquez said:

“The never-ending conflict in this community helps us remember what is important in life. My grandparents always say a soul without land is navigating without destination…I start thinking – and I believe the whole world needs to start thinking – what do we want for the future? Because if we continue this way, humanity will come to an end. “

Most documentaries tell stories in the past. But events in The War We Are Living continue to unfold. The story isn’t over. Sadly, the La Toma case isn’t isolated. Other communities face eviction and death threats from paramilitaries. While President Santos recently signed a bill into law that would “return 5 million acres to landless peasants,” he believes paramilitaries don’t pose a real threat. But Carabali and Marquez still fear for their lives.

Echoing concerns of Occupy Wall Street protests about the elite 1% controlling resources, Colombia contends with massive class inequality and a war fueled by greed. Afro-Colombians and Indigenous Colombians confront discrimination and concentric layers of oppression including racism and classism. Facing death threats to themselves and their families, female leaders like Clemencia and Francia bravely negotiate for peace and demand justice. They refuse to be intimidated. They refuse to leave their land. They refuse to be silenced.

Watch the full episode of The War We Are Living online or on PBS.

—–

Megan Kearns is a blogger, freelance writer and activist. She blogs at The Opinioness of the World, a feminist vegan site. Her work has also appeared at Arts & Opinion, Fem2pt0, Italianieuropei, Open Letters Monthly, and A Safe World for Women. She earned her B.A. in Anthropology and Sociology and a Graduate Certificate in Women and Politics and Public Policy. Megan lives in Boston with more books than she will probably ever read in her lifetime.

Megan contributed reviews of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo,

The Girl Who Played with Fire,

The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet’s Nest,

Something Borrowed,

!Women Art Revolution,

Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?,

The Kids Are All Right (for our 2011 Best Picture Nominee Review Series),

The Reader (for our 2009 Best Picture Nominee Review Series),

Man Men (for our Mad Men Week),

Game of Thrones and The Killing (for our Emmy Week 2011),

Alien/Aliens (for our Women in Horror Week 2011),

and I Came to Testify,

Pray the Devil Back to Hell and

Peace Unveiled in the

Women, War & Peace series. She was the first writer featured as a Monthly Guest Contributor.