This guest post written by Maddie Webb appears as part of our theme week on Women Scientists.

I am a fan of biopics. And, judging by the success of films like The Theory of Everything and The Imitation Game, biopics about scientists are definitely viable projects for Hollywood. However, issues around equal gender representation in film are compounded by many female researchers’ accomplishments being erased from history, resulting in very few women being key players in scientific biopics. As a woman studying for a science degree, this absence is as painful as it obvious.

So in a bid to restore balance (and an excuse for me to nerd out), here are 5 female scientists that deserve to have their stories told on the silver screen.

1. Katherine Johnson and the women of NASA — Physicists

NASA is awesome. That’s probably one of the least controversial statements ever, but did you know that it was a group of African American female mathematicians that gave the USA the edge in the space race?

This first one is a bit of a cheat since it’s already being made into a movie, but since it seems to be flying under the radar of even my most devoted cinephile friends, I’m using this list as an excuse to talk about it. Hidden Figures, is the sophomore effort of director Theodore Melfi, written by Allison Schroeder, and the film adaptation of a book of the same name written by Margot Lee Shetterly.

Taraji P. Henson has taken a break from owning season 2 of Empire and is set to star as Katherine Johnson, the physicist turned space scientist badass whose calculations were so accurate, NASA would call her to verify their own computer-generated numbers. Johnson graduated high school at the age of 14 and graduated college at 18. At NASA, she calculated launch windows and space flight trajectories. She has also “co-authored 26 scientific papers.”

Janelle Monáe and Octavia Spencer, who are also playing scientists, round out the leading ladies roster and the film is expected to touch on the civil rights era from the unique perspective of women working inside an institution like NASA. In a world where the representation of Black women in positive roles is still lacking, there’s plenty to get excited about in this story.

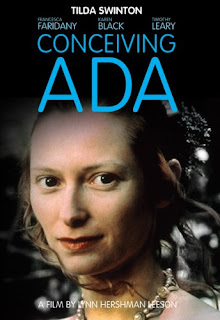

2. Ada Lovelace — Mathematician

How this women’s story still doesn’t have a film adaptation I will never know. Largely abandoned by her famous but useless father Lord Byron, Ada Lovelace is widely credited with writing the first algorithm designed to be performed independently by a machine. In other words, a woman born in 1815 was the first person to write computer code. HOW IS THIS NOT A MOVIE?!

It’s also a tragedy. Lovelace by all accounts was a woman ahead of her time and her genius went unappreciated by her overbearing mother, her indifferent husband, and even Charles Babbage, the man who invented the counting machine she wrote the code for. She died aged 36 from uterine cancer and it wasn’t until the beginning of the digital age that she was rightfully recognized as a pioneer of computing.

Her prominence in civil society would also the perfect excuse for a film to include some famous historical faces. Lovelace moved in the same circles as Charles Dickens, Michael Faraday, and fellow lady scientist Mary Somerville. Plus doesn’t everyone love a good period film?

3. Rosalind Franklin — Chemist

Sometimes history forgets people; sometimes people “borrow” your work and never give you proper credit. Thus goes the story of Rosalind Franklin, an X-ray crystallographer whose work was instrumental in the discovery of the structure of DNA, the importance of which cannot be understated in modern biology. Trust me on that one.

Born in 1920 to an upper class Jewish family in England, Franklin became a research associate at King’s College in 1951. She ruffled a lot of feathers in the scientific community and left her post after just 2 years due to clashes with her superiors. Fellow researchers Watson and Crick used the images she produced in her research (and was forced to leave behind at King’s) without her knowledge to help determine the structure for DNA and win a Nobel prize, which Watson later admitted should have also been awarded to Franklin.

One reason why this story is a more likely candidate for a film adaptation is that a play about Franklin’s life, Photograph 51, starring Nicole Kidman recently concluded a very successful run on the West End. It would certainly be interesting to see a film about a Jewish woman dealing with institutionalized sexism but also the growing anti-Semitism in 1930’s Europe and the repercussion of World War II.

She will never get the Nobel Prize but that doesn’t mean Rosalind Franklin shouldn’t get her time to shine.

4. Vera Rubin — Astronomer

Vera Rubin is a pioneer astronomer in the field of galaxy rotation and dark matter, one of the most important concepts in modern physics. And if absolutely none of the previous sentence made any actual sense to you, welcome to the world of theoretical physics.

At the age of 22, Rubin presented her first thesis on galaxy rotation and was essentially laughed out of the room. Her peers mostly dismissed her argument; the resulting paper she authored was rejected by the major astronomy journals of the time. On top of that, she was later barred from pursuing her theories further at Georgetown’s Applied Physics Lab “because wives were not allowed” there.

It turns out Rubin’s thesis was right. Not only is Rubin credited with providing research and evidence of dark matter, the Rubin-Ford effect, which “describes the motion of the Milky Way,” is named after her and fellow astronomer Kent Ford.

Rubin is pretty much a modern-day Alexander Hamilton in regards to her work ethic. As of 2013, she has at least co-authored 114 peer-reviewed papers, while somehow finding time to raise 4 children who also all have PhDs. Basically, she’s the head of the science equivalent of the Von Trapp family, and if you don’t want to see that film, then there is simply no pleasing you.

She’s also the definition of a role model; an outspoken advocate for encouraging more women into STEM fields and combating peer review gender bias, while staying endearingly humble about her own achievements.

In her own words: “Fame is fleeting, my numbers mean more to me than my name. If astronomers are still using my data years from now, that’s my greatest compliment.”

I say we give her a movie anyway.

5. Flossie Wong-Staal — Biologist

Maybe as a biologist I’m just biased, but Flossie Wong-Staal’s life story in my opinion would make the most interesting film.

Born Yee Ching Wong in communist China, Wong-Staal fled to Hong Kong with her family when she was 5 years old and she was given the English name Flossie after a typhoon that hit the family’s home. The name turned out to be appropriate, since in her professional life, Flossie was a force of nature.

Moving to the U.S. alone at only 18, Wong-Staal was the first female member of her family to go to college. After earning her PhD in molecular biology, she went on to become a world-leading expert on HIV. She was the first scientist to successfully clone the virus and helped prove that it caused AIDS, which was the medical and geopolitical issue of the time. Her continued research made it possible for the development of an HIV test, saving countless lives worldwide. Wong-Staal also founded her own pharmaceutical company and still works today, as if she wasn’t cool enough already.

From a cinematic perspective, it would be interesting to see the AIDS epidemic from the perspective of the scientists that try to combat one of the most deadly viral outbreaks in modern history. Additionally, a film based on the achievements and contribution of an immigrant in Western culture would be appreciated, considering the current political climate.

So there is my personal list of the women in STEM that I’d like to see on screen. Hopefully in the future some of these ladies will get the recognition they deserve and inspire more girls to follow in their footsteps; what a legacy that would be.

Photo of Katherine Johnson by NASA in the public domain.

Image of Ada Lovelace; portrait by Alfred Edward Chalon in the Science Musuem, London in the public domain in the U.S.

Photo of Dr. Rosalind Franklin by Robin Stott via the Creative Commons License.

Photo of Vera Rubin and others at the Women in Astronomy and Space Science 2009 Conference by NASA in the public domain.

Photo of Dr. Flossie Wong-Staal by the National Institutes of Health in the public domain.

Maddie Webb is a student currently studying Biology in London. If she doesn’t end up becoming a mad scientist, her goal is to write about science and the ladies kicking ass in STEM fields. In the meantime, you can find her on Twitter at @maddiefallsover.