Trigger warning: A large part of this post discusses a character who is suffering

from Bulimia.

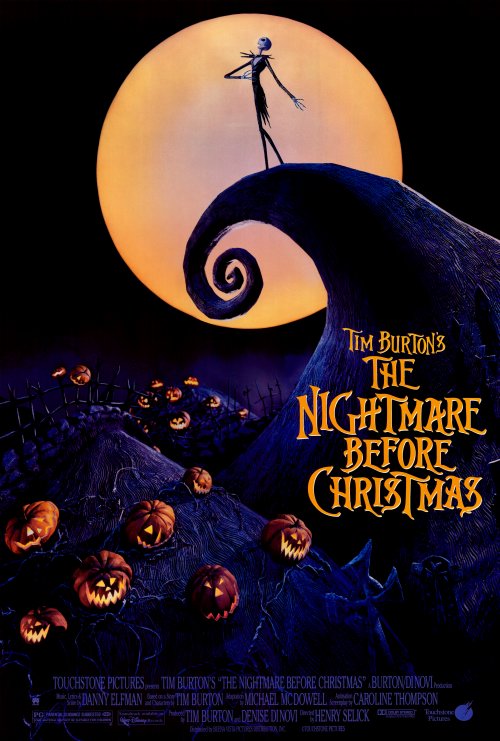

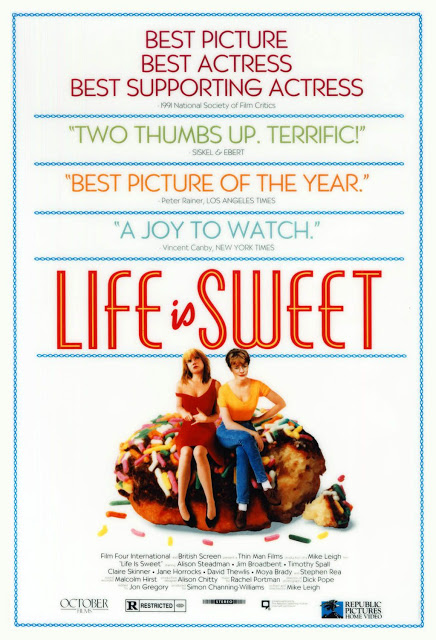

In many ways Mike Leigh’s 1991 film Life is Sweet should not be extraordinary. An almost entirely improvised piece, it takes place in a working class family home in the unremarkable London suburb of Enfield.

The preparation and consumption of food is a running theme throughout the film. Family man Andy (Jim Broadbent) is a chef in a large, anonymous corporation who, at the start of the film, buys a fast food van* in order to fulfill his ambition to work for himself. Soon after that, his buoyantly optimistic wife Wendy (played charmingly by Alison Steadman) takes a waitressing job at the Regret Rien, a Parisienne-themed eatery that a friend of the couple has recently opened.

The couple’s twin daughters also demonstrate an interest in food, albeit in very different ways. Nicola (Jane Horrocks), a tiny chain-smoking bulimic, binges and purges sweets and chocolate every night, seemingly punishing herself for a crime that’s never revealed. Her sister Natalie has a stereotypically normal relationship with food — managing to sit and eat with her parents, when her sister never can — but works as a plumber, something which was still seen as a bit icky, and not a suitable job for a woman in Britain in the early 90’s. And yes, that was because she may have had to come into contact with human waste.

In spite of its seemingly mundane subject matter, Leigh’s film is superb. Naturalistic to the point where it could be a fly-on-the-wall documentary, it’s also brilliant in its depictions of parts of the female experience that many films approach in ways that make them seem gimmicky.

A young woman with an eating disorder lashing out at everyone around her but never hurting them more than she does herself? Check. A mother desperately trying to stay strong and support her mentally ill child, in spite of the frustration that child’s self-destructive tendencies cause? Check. A closeted lesbian dreaming of escape but ultimately remaining stable and strong for everyone around her? Check.

And that says nothing of Andy, the hard-working but mildly baffled father figure. And yet, despite the tropes and the presentation of these character’s lives as “tragi-comic” none of it is tacky, or even remotely depressing. It is in fact an unusually uplifting watch.

[*Fast food vans may be a British phenomenon. They are mobile kitchens, which park on the side of busy roads and serve snacks such as burgers, bacon sandwiches, baked potatoes and hot dogs to passers-by. Considered low-class, their offerings are typically delicious.]

Family Dynamics

|

| L-R: Nicola (Jane Horrocks) and Wendy (Alison Steadman) in Life is Sweet |

To my mind, this film’s main characters are Wendy and Nicola. Although she is undoubtedly a loving mother to both her girls, most of Wendy’s time and energy is taken up by Nicola, and Nicola’s seemingly needless rage at the world around her.

Natalie, though often present — and an interesting depiction of a lesbian who remains closeted — is side-lined while the film-maker and characters concentrate on her sister’s struggle with an eating disorder. Her apparent contentment with her life and realistic ambitions (she wants to take a holiday in America) mean that she does not demand a lot of attention from anyone, including the viewer. Readers who’ve lived with such an illness, or someone suffering from one, may recognise the reality of this on-screen scenario.

Andy, despite being the one family member who gets to fulfill an ambition in the film, also plays second fiddle to his wife and mentally ill daughter. It’s possibly because he spends much of his time either daydreaming or at work, and is thus unaware of the extent of Nicola’s misery, and his wife’s increasing concerns about it.

Wendy and Andy, it’s revealed, struggled to raise their children. There was never enough money, forcing Andy to remain in a job he “hated” for years to support them, while his wife could not pursue her goal of completing a university education. That one of their children reacts to her life – which is, after all, largely funded by her parents’ catering jobs – by developing bulimia nervosa is an obvious manifestation of self-loathing.

Nicola becomes increasingly reclusive and agitated throughout the film, abusing her father for being a “capitalist” when he invests in the fast food van, and refusing to sit with her family at meal times or even mix with anyone outside the family home.

Throughout the film she conceals her bulimia from both of her parents, only agreeing to tell her parents about it in the film’s final scene. Her twin has known about it – and about the locked suitcase full of sweets and chocolate she keeps under the bed – because she hears her bingeing then purging each night, a painful secret she keeps not simply because she loves her sister, but because she also has no idea what to do.

In one scene, Nicola has a blazing argument with Wendy that indicates that she may finally be ready to recover. Shame-faced, Nicola screams that she knows how much the whole family hates her, and that is why they’re trying to force her to eat with them/ mix with other people/ live her life.

Exasperated, her mother snaps, “We don’t hate you! We bloody love you, you stupid girl!” reducing Nicola to tears.

It’s an exchange that cuts to the core of their relationship, and to the thinking of an eating-disorder sufferer. If they loved her, Nicola thinks, they’d let her fulfill the death wish the disease implants in sufferers. Her family, though not entirely aware of what’s going on, love her too much to let her fulfil that particular ambition.

Nicola’s Behaviour

|

| Nicola (Jane Horrocks) in Life is Sweet |

Like many bulimics, Nicola hides much of her illness from her family. Its most obvious manifestation is probably her refusal to eat with them at mealtimes, which could easily be taken for rudeness rather than any kind of secretiveness.

One of the more interesting — or just salacious — quirks of her disorder is that food is essential to her sexuality. She cannot become aroused unless her lover (David Thewlis) ties her up and licks chocolate spread from her chest. It’s as if even when in the middle of sex with a man who genuinely cares about her, when she should finally be able to indulge herself without punishment, she is still determined to deny herself. Granted, the metaphors in this film aren’t particularly hard to decipher.

I’ve already mentioned that she keeps a locked suitcase full of sweets and chocolate under her bed, which she uses to abuse her body with each night, stuffing herself full of them before plunging her fingers down her throat in order to bring all that food back up. It’s not until one has had an illness that causes repeated vomiting (this is my last reference to puke, I promise) that one realises how much bulimia nervosa is an act of self-abuse.

To deliberately and repeatedly purge day-in-day-out for months or even years at a time is to truly hate oneself because it is such a horrible experience. Jane Horrocks’ depiction of this level of self-hatred and the harm a person can do to their own body is truly insightful.

I don’t want to recommend this film to anyone who’s suffering or is in recovery from an eating disorder in case it is triggering, but I have heard sufferers say that Horrocks’ performance helped their loved ones to understand the realities of their disorder. I thought that was worth mentioning.

The Regret Rien

|

| L-R: Aubrey (Timothy Spall) and Wendy (Alison Steadman) in Life is Sweet |

A little way into the film, Wendy takes a job at the Regret Rien, a restaurant that’s just been opened by a family friend. Parisienne-themed and — there’s no way around this — as clichéd as fuck, the Regret Rien is also in possession of one of the most revolting menus in modern cinema (and I’m including films in which

characters cannibalise each other in that).

A quick sample of what’s on the menu: Saveloy on a Bed of Lychees, Liver in Lager, Pork Cyst, Prune Quiche, King Prawn in Jam Sauce, Tongues in a Rhubarb Hollandaise, Tripe Soufflé, Chilled Brains, Prune Quiche, Grilled Trotter with Eggs Over Easy.

Pork cyst, for God’s sake. And Tripe Souffle.

Apparently meant as a parody of the nouvelle cuisine trend that swept British restaurants in the early 1990’s, it’s not much of a surprise the venture looks set to fail. Its pretentious menu and clichéd décor are directly contrasted with the plain and much more popular food served up by Andy’s fast food van.

By the end of the film the viewer comes, in no uncertain terms, to like the family depicted in it (even Nicola), and a lot of their likeability comes from the fact that they are “salt of the earth” people who aren’t pulled in by gimmicks such as the push bike that sits in the bay window of the Regret Rien.

That’s not to put down working class people with a love of French cuisine, and a dislike of fast food. It’s just to point out that when it comes to cooking, the simplest recipes — like the simplest people — are often the best.

Conclusion

There’s a lot of food in Life Is Sweet, most of it — from the chocolate that Nicola purges to the burgers Andy cooks up, to the vile cuisine Wendy is meant to be serving — bad. But there’s also masses of love.

As I’ve admitted, the metaphors Mike Leigh employs aren’t particularly hard to decipher. But this is a lovely film, a film that takes a mostly realistic look at the difficulties life throws at us and points out that as long as we ignore the pretentious, over-complicated rubbish in favour of the people who love us enough to support us through them, we will be okay.

———-

.jpg)