This repost by Ren Jender appears as part of our theme week on the Academy Awards.

In one of the first scenes of Two Days, One Night, the newest release from the Belgian writer-directors Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne, we see the main character Sandra (played by a dressed-down Marion Cotillard) receive some bad news on the phone. She says out loud to herself afterward, “Don’t cry.”

Sandra, we later find out, has been on sick leave from her job for the past few months because of clinical depression. The phone call is from her friend at work, Juliette (Catherine Salée), who tells her that the rest of the laborers at their place of employment (which seems to be a small manufacturer of solar panels) have voted to accept a €1,000 bonus (about $1,200), which the foreman has offered in exchange for their agreement to lay Sandra off (Western Europe: a fairytale land where a boss asks his workers for permission to lay off their colleague–and offers them money to do so). The overwhelming majority of the workers (all but two of the 16 of them) have voted against her.

Juliette tells Sandra the foreman has misled the others into thinking if they didn’t agree to get rid of Sandra one of them might be laid off instead. So as the plant’s big boss is leaving the parking lot in his sports car to start his weekend, Juliette and Sandra plead with him to hold another vote, with a secret ballot, first thing on Monday morning. He just wants to get out of there, so he agrees.

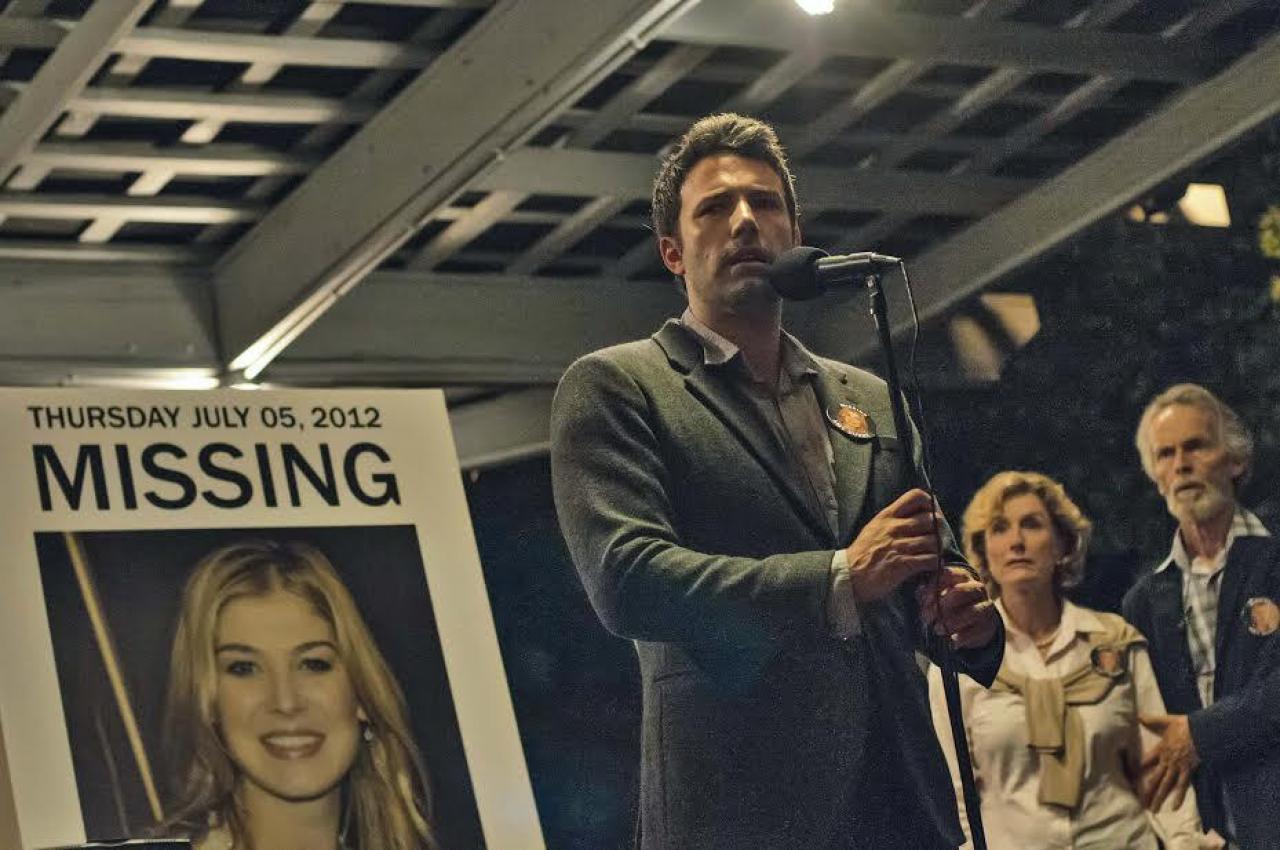

For the rest of the film Sandra, with the support of her husband (Fabrizio Rongione), and to a lesser extent, Juliette, tries to convince the others (after finding their home addresses and tracking them down) to let her stay. Of course voting against Sandra was easy when they didn’t have to face her and hear her say that she doesn’t want to be jobless and swear that she’s ready to go back to work (even as we in the audience, who have seen how frail she still is, wonder if she’s telling the truth).

One of her coworkers (part of the handful of Black and brown immigrants also more likely to be let go) is unexpectedly emotional; Sandra looks confused as he weeps about voting against her on Friday and thanks her for the chance to redeem himself. Others, including a woman Sandra had thought was her friend but refuses to see her, are surprisingly cold–or outright hostile. They want that €1,000 and don’t care if getting it means she will lose her job. Some make excuses and tell her they’re not the ones who set Sandra’s continued employment against their bonuses. She replies, quicker and more astutely than we expect, that the choice isn’t of her making either.

Cotillard, her hair in a straggly ponytail, wears skimpy, summer tank tops, but is so slouched and tense for most of the film, her body is like a backwards “S.” She comes across as both convincingly desperate and working-class (not something all red-carpet actresses are capable of). Like Violette, Two Days, One Night isn’t afraid to show its protagonist at her worst. Sandra, like Violette, hates the thought that the concessions the others are making for her are motivated by pity. She constantly wants to give up, taking to her bed in the middle of the day, even as her husband gently pushes her saying, “Why not try?” and “Don’t give in. You have to fight.”

This film, like Violette, challenges the lie that most films tell, especially those released in time for awards season, that after a few minor setbacks a protagonist will, with uplifting music on the soundtrack, stand up straight and face adversity head-on with courage and maximum photogeneity. But the people who do extraordinary things often do them after a lot of bone-crushing rejection. They feel like miserable failures. They cry. They consider quitting all the time. We all like to think we face the trouble that comes our way like Wonder Woman, but when events take a turn for the worse we’re more like Dr. Smith on the old TV show Lost In Space, crying in an increasingly hysterical voice, “Oh dear, oh dear, oh dear.”

Women in films are even less likely to engage in this kind of dispirited struggle. Instead an actress usually plays the wife, mother, or girlfriend whose job it is to be “strong” and rub the hero’s back while he battles against his own obstacles. She talks reassuringly to him whenever he doubts himself, the exact same way Sandra’s husband does with her here.

Sandra’s quest is not just an indictment of capitalism but also touches on the responsibility we feel for our fellow human beings–how deep (or not) our empathy runs for the people we talk to and work alongside every day. Seeing Sandra’s surprise at who votes for her and who votes against her makes us wonder how well we know our own coworkers. We see her smile after one small triumph and in her next encounter we see her literally knocked down. We count with her as she accumulates four then five votes and when she talks to a man who just wants his money see her wisely clam up about which coworkers are voting for her. The long, frustrating, seemingly impossible task in front of Sandra could stand in for a number of others: writing a book, staying in a marriage–or making a movie.

And after we, along with Sandra, have nearly given up hope for her getting her job back, we see her become unexpectedly resilient–and the solution to her problem become more complex. Her late transformation reminds me of the redemption of another depressed character in a French-language film, Delphine in Eric Rohmer’s great Summer. Just as we hear the wonder in Delphine’s voice in the last line of that film, we hear a newfound strength and certainty in Sandra’s voice as she talks on the phone to her husband at the end. The two days and one night of the title have changed her, maybe forever.

[youtube_sc url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=06BNjqSsGqo” iv_load_policy=”3″]

Ren Jender is a queer writer-performer/producer putting a film together. Her writing, besides appearing every week on Bitch Flicks, has also been published in The Toast, RH Reality Check, xoJane and the Feminist Wire. You can follow her on Twitter @renjender