If you watch the movie trailer for

Hope Springs, you’ll see a lot of comical moments set against the backdrop of some lighthearted happy music…

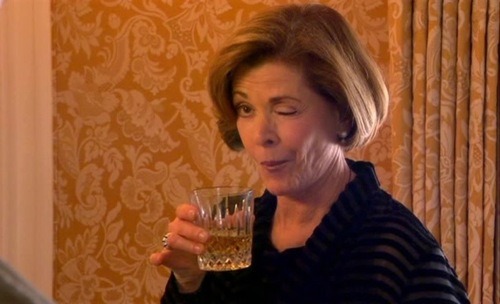

…including Meryl Streep’s character telling her kids that she and her husband—played by Tommy Lee Jones—got each other a new cable subscription to celebrate their 31st wedding anniversary.

…Streep smiling happily when Jones joins her on the plane to go to “intensive couples therapy.”

…Jones cracking wise about the experience: saying things like “I hope you’re happy” when he boards the plane and “that makes one of us” when their therapist—played with both understated gravity and empathy by Steve Carrell—says he’s happy the two of them are there.

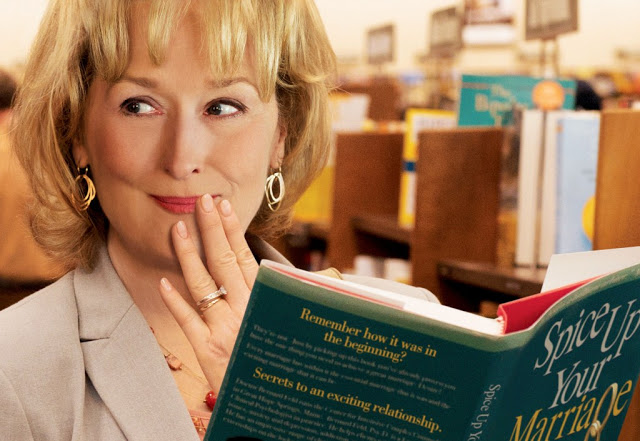

…Streep asking a bookstore clerk for a book called Sex Tips for a Straight Woman by a Gay Man. (A book, by the way, I would like to have.)

…Streep sitting on a toilet eating a banana while reading the aforementioned book (rather than using said banana for its intended purpose).

…Streep laughing bashfully when salty bartender Elizabeth Shue gets a bar full of locals to admit they’re not having sex either. (Shue’s only appearance in the film, I must sadly note.)

…Streep and Jones laughing together over their therapist’s formal way of talking about sex.

…Streep shaking her head in a lighthearted manner at Jones while Jones dances in front of her.

And while all this is happening, the screen reads:

From the director of THE DEVIL WEARS PRADA … comes a comedy about love…and the things we’ll do to get it.

Finally, the trailer closes with Streep and Jones running into the neighbor with whom Jones admitted in therapy he’d like to have a threesome. The woman has just adopted her third Corgie, and the trailer ends with her saying,”Three’s the limit!”

It all feels very light, funny, silly, and—this is important—optimistic, even hopeful, an idea of course reinforced by the title, Hope Springs.

But this trailer is completely misleading because

Hope Springs is not a comedy—unless you’re talking about

the tradtional Shakesperian definition of a comedy, which assumes that on the way to finding happiness the characters suffer through some incredible tragic experiences.

No, the majority of this movie is more dark than light, more pessimistic than hopeful. In fact, sometimes it’s so dark that it’s hard to watch. (Not The Hurt Locker hard to watch, but still hard to watch.)

This is because Hope Springs is a movie about two people who are desperately unhappy—in marriage and in life. And it is their unhappiness that dominates most of the movie. They certainly spend more time feeling alienated or alone than they do being happy—whether they are together or apart.

And that makes me happy.

It makes me happy because it is so rare that we see a mainstream movie showing average Americans who are desperately unhappy, a condition that sadly affects more of us than it should given how relatively easy most of our lives are.

In most mainstream movies, we are shown something wholly different from these two miserable people … not their polar opposite, but still people who are mostly happy but have a tiny sliver of unhappiness in their life, a sliver which is usually located in their romantic life. As the movie progresses, these mostly happy people, of course, find romance and then all is well in the world.

In other words, most mainstream movies about couples are not at all realistic and not really all that interesting.

But Hope Springs, thankfully, isn’t that simple-minded.

At the beginning of the film, the unbelievably talented Streep and Jones are shown wallowing in the mud puddle of routine and mediocrity. Their lives are horribly mundane—they wake every day at the same time, they eat the same meals and watch the same TV shows, and, most importantly, they spend their time not interacting in the same frustrated fashion.

And some of the clips that look cute and comical in the preview—like when they mention their new cable subscription to their kids at their anniversary dinner—are much darker inside the actual movie, where it seems that absolutely nothing is able to even temporarily lift their suffocating misery. Even on their anniversary, they can’t even look each other in the eye, much less speak to each other, a scene that reads as more tragic than funny when you see it in context.

These tragic occurences continue throughout the movie. From the moment when Streep is packing her suitcase for couples therapy, crying as she thinks about the fact that Jones has said he doesn’t want to join her, to the two different scenes when they each run out of therapy on different occasions after becoming completely overwhelmed by the problems they face as a couple. *SPOILER ALERT* To the brutal scene when they finally try to have sex but ultimately fail, leaving Streep to wonder out loud if Jones is no longer attracted to her because she’s overweight and old. It’s obvious to the viewer that this is not the case, but watching Streep wimper about the baby weight she never lost after her husband stops banging her mid-coitus is utterly heartbreaking. *END OF SPOILER*

These are the kinds of moments that dominate the film, clearly demonstrating that these people are miserable in a way that is not at all happy or light or silly.

But rather is very real.

And the things they talk about in therapy are real too—why they no longer have sex, why they don’t sleep in the same bed, why they play out the same ignore-each-other script every day of their lives, why they never do anything for each other anymore, why their gifts are for the house and not each other, and even more hard-to-talk-about issues like what they fantasize about and whether or not they still masturbate.

The latter discussion made me wish—for a split second—that I wasn’t sitting between my husband and my mother while watching this scene unfold, but ultimately I was so thrilled the film didn’t flinch from the emotional honesty of these uncomfortable moments that I was able to get past the awkwardness of the situation.

I had invited my mother to see the movie with us because I’d had the wrong impression—from the misleading trailer—that it was going to be a well done but cliched and light-hearted rom-com.

But as I said, Hope Springs is far from light entertainment. It’s a movie that makes you think.

It makes you think about what it means to have a healthy relationship and about how you can lose that even with someone you love. It makes you think about how important sex and romance are to a successful relationship. It makes you think about the problems with falling into stereotypical gender roles. And, most importantly, it makes you think about how happiness is more important than being in the wrong relationship.

In that way, Hope Springs feels more like Sex and the City for seniors than a rehash of some of Streep’s other rom-coms—like It’s Complicated and Mamma Mia!—both of which were fun and had some thoughtful interludes, but were still, in the end, just light entertainment.

The woman who wrote the screenplay for Hope Springs—Vanessa Taylor—is new to film but has written for critically-praised television shows such as Game of Thones and Alias, making me wonder if maybe, just maybe, Hope Springs is a sign Hollywood is finally willing to let more serious writers take on comedy, something we’ve seen with only a handful of other screenwriters such as Alexander Payne and Diablo Cody. And if this were to happen even more, it makes me wonder if we could move away from the predominantly vacuous junk that has passed as comedy about women for the past decade—the so-called rom-com—so that we can finally return to our more Shakespearian roots.

At the very least, this movie gives me that hope.

Molly McCaffrey is the author of the short story collection

How to Survive Graduate School & Other Disasters, the co-editor of

Commutability: Stories about the Journey from Here to There, and the founder of

I Will Not Diet, a blog devoted to healthy living and body acceptance. She teaches English and creative writing classes and advises writing majors at Western Kentucky University in Bowling Green, Kentucky.