|

| It’s sexy to regard subjective truth as hooey |

‘Won’t Back Down’ Causes Mixed Feelings

|

| Viola Davis and Maggie Gyllenhaal in “Won’t Back Down” |

“For Walden, the film is a second shot at an education-reform movie. With Mr. Gates and the progressive-minded Participant Media, Walden was among the financial backers of the documentary ‘Waiting for ‘Superman.’ ”That film, released in 2010, advocated, as potential solutions to an education crisis, charter schools, teacher testing and an end to tenure. But it took in only about $6.4 million at the box office and received no Oscar nominations after union officials and others strongly attacked it.‘We realized the inherent limitations of the documentary format,’ said Michael Bostick, chief executive of Walden. Now, he said, the idea is to reach a larger audience through the power of actors playing complicated characters who struggle with issues that happen to be, in his phrase, ‘ripped from the headlines.'”

“I personally remember lots of overstuffed rolling tote bags (an especially popular option among teachers who needed to bring work home after school ended) and reusable coffee mugs (popular among us newbies who often worked such long hours we barely saw daylight during the fall and winter months) in the school I worked in. Likewise, the school day itself was often a whirr, with teachers bouncing around among 25, 30 or more students at a time during lessons; moving in and out of meetings, planning and professional development sessions; and making calls and handling other daily logistics during “free” periods.

Yet in the movie, it is repeatedly asserted that the union contract prevents exactly this kind of work from taking place. (I suppose all those graded papers, lesson plans, letters of recommendation and after-school activities just happen by magic?) In this school, the contract and the union that backs it are blamed for teachers not helping kids and refusing to work after school. And except for the two teachers closest to the desperate mother played by Maggie Gyllenhaal, these teachers don’t appear to do all that much during the school day, either. The dour, bitter teachers on display during the first two-thirds of this movie looked very little like the committed, passionate teachers I know– though I suppose it’s easy for a screenwriter to misread teachers’ bouts of fatigue or frustration as bitterness if they don’t understand where that frustration comes from. Managing 30 or so people at once requires a constant stream of attention and thousands of split-second decisions every day. Add to that inadequate resources and escalating demands, and formerly bright smiles will indeed begin to dim.”

‘Phantom of the Opera’: Great Music, Terrible Feminism

|

| Phantom of the Opera Movie Poster (Source: Wikipedia.org) |

|

| Gerard Butler as The Phantom (Source: Fanpop.com) |

|

| Raoul (Patrick Wilson) and Christine (Emmy Rossum) waltzing (Source: Fanpop.com) |

|

| Unmasked Phantom (Gerard Butler) holding a struggling Christine (Emmy Rossum) (Source: Fanpop.com) |

Myrna Waldron is a feminist writer/blogger with a particular emphasis on all things nerdy. She lives in Toronto and has studied English and Film at York University. Myrna has a particular interest in the animation medium, having written extensively on American, Canadian and Japanese animation. She also has a passion for Sci-Fi & Fantasy literature, pop culture literature such as cartoons/comics, and the gaming subculture. She maintains a personal collection of blog posts, rants, essays and musings at The Soapboxing Geek, and tweets with reckless pottymouthed abandon at @SoapboxingGeek.

‘The Mindy Project’ : A Case for the Female Anti-Hero

|

| ‘The Mindy Project’ premiers Sept. 25 (the pilot is available on Hulu). |

Mindy Kaling’s new sitcom, The Mindy Project, gives us the rare fully flawed female anti-hero in a prime-time comedy. What’s striking in the pilot episode (Hulu is previewing the pilot before the show premiers on Fox on Sept. 25), is that Mindy’s character, Mindy Lahiri, an OB/GYN, isn’t particularly lovable. In fact, she’s kind of an asshole.

And it’s great.

Lahiri gets trashed and attempts to ruin her ex’s wedding. She loves romantic comedies in a completely shallow, selfish way. She makes inappropriate (even racist) jokes. Was I being seduced by the fact that M.I.A. was blasting in the background during the show’s climax? Why did all of this work so well for me?

|

| Lahiri, at her ex’s wedding, drunkenly insults the couple (including jabs at his new wife’s ethnicity). |

I realized that it felt good to see an unlikable female protagonist. It felt good to see a true female anti-hero. Of course, it’s clear that we are supposed to root for her, and can do so easily. Lahiri as a protagonist fits in more with Sterling Archer, Michael Scott, Larry David and Jeff Winger than she would with Leslie Knope and Liz Lemon. We accept men as lovable assholes, but for women it’s often a different story.

The expectations we have for female characters in entertainment rival the expectations we have for women in our culture. Be funny, but not crude. Be pretty, but not vain. Be confident, but not prideful. Be excellent at your career, but don’t sacrifice love and motherhood. Be sexy, but not sexual.

Our expectations for men are much simpler, and less impossible. In fact, the expectations could be characterized as “lack thereof” (this is problematic in its own way). Perhaps this is the reason why we embrace the male anti-hero (whether it’s a sitcom, hour-long drama, film or Ernest Hemingway novel). Audiences expect men to be crude, shallow and unpleasant on many levels. These low expectations open up countless opportunities for complex male characters.

|

| “I’m sorry, disorderly conduct? Aren’t there rapists and murderers out there?” Upon release from her arrest, Lahiri shows little remorse. |

Don’t get me wrong, I love Knope and Lemon. Knope’s character–the entire show, really–is a shining example of feminism in practice. Lemon is flawed, but is also hyper-self-aware and apologetic for herself in many ways. Both of those characters want to be liked. Lahiri (a true model Millennial) doesn’t seem like someone who would apologize to anyone. She just wants it all.

I look forward to having a relationship with a female anti-hero like I have with so many male anti-heroes on TV. I look forward to laughing and/or cringing at some of the character’s words and actions. Lahiri is not what we’ve been taught is the ideal. She’s real, and says and does things that don’t “fit” the ideal mold. Of course it goes without saying that seeing a curvy woman of color in a leading role feels pretty amazing.

We don’t need every female protagonist to be a true hero. We simply need more complex depictions of women–the good, the bad and the accurate. We shouldn’t expect our female protagonists to keep sweet any more than we should ourselves.

A reviewer at The Atlantic Wire, in a disappointed review of the pilot, says of the show’s premise, “… I’m worried this particular setup might not be the one. Bawdy talk in an OB/GYN office followed by drunken antics in a mini dress is all well and good, I guess. But Kaling, to some of us at least, has always seemed a bit better.”What does this mean, exactly, besides A. the show is too feminine, and B. she should be “better” than bawdiness and drunkenness? That’s not the point and is the whole point, all at once.

Lahiri grew up in an era of idealized depictions of love and womanhood via Meg Ryan and Sandra Bullock rom-coms. She wants that happy ending, but doesn’t seem to want to change herself for it. She’s clearly excellent at her career. At the end of the day–and at the end of the episode–she just wants to get laid. So she does.

She smiles toward the camera and we’re invited not to judge, and not to clutch our pearls and wish for a more perfect female character. We’re simply supposed to come along for the ride.

—

Leigh Kolb is a composition, literature and journalism instructor at a community college in rural Missouri.

Call for Writers: Women and Gender in Musicals

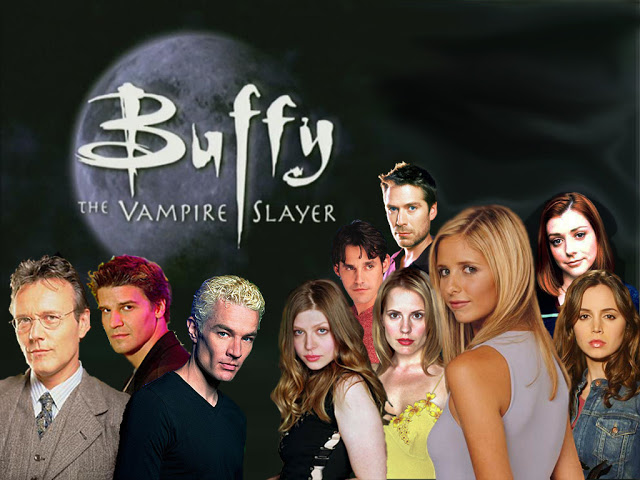

Buffy the Vampire Slayer Theme Week: The Roundup

YouTube Break: Buffyverse Season 1 Trailer

Buffy the Vampire Slayer is a series that redefined television in many ways. It combined drama, comedy, romance, action, and horror in an original and unique way. It portrayed a lesbian relationship as mainstream. It centered around metaphors for the trials and tribulations of everyday life that all its viewers, young and old, could relate to. But most importantly, creator Joss Whedon fashioned a world in which the stereotypes of teenage girls (and ultimately all women) were debunked and left at the wayside.

As a lover of Buffy and a theologian, I want Buffy to be theologically and metaphysically coherent. I want it eitherto establish one metaphysical system as true for the world it portrays, or to represent a believable variety of metaphysical beliefs among its characters. The former is an entirely lost cause; the latter is frustratingly undercooked. Willow’s Judaism is wholly Informed, and her turn to Wicca is entirely to do with magic. There is no sense at all of Wicca (or any other religion) as an ethical code, as a way of making meaning, as a way of personally relating to the world and others in it.

Around dinner tables and over cups of coffee, nearly a decade after the series concluded, I’ve witnessed this discussion unfold time and again. And, I think this is the key interpretative moment: are women, the series asks, dependent on men to create a new field of play? Or might the show call into question the norms and expectations of both genders? The answer to these queries may well be found in Spike’s role in the series’ finale. Certainly a number of conversations turn to Spike’s role. In its layers of ambivalence that call upon men to not only transgress but efface normative boundaries, it points to the latter.

YouTube Break: Buffyverse Season 2 Trailer

And then, of course, Buffy kicked a lot of ass. A very serious amount of ass. Over the course of the show’s seven television seasons, she averted multiple apocalypses. She punned and killed all very large monsters and vampires that she came across. She added clever insult to injury. She never apologized for not being a dumb, weak girl. And it was very physical — in the canon of the show, a Slayer is given extra-human powers of strength, speed and agility. She was a fashionable girl’s girl, and she slayed creatures that go bump in the night. It was Girl Power at its late-1990s peak and taken to an excellent extreme.

Though the show suffers from no shortage of powerful women, the ways in which they relate to one another throughout the series is a constant struggle. This is because the dominant patriarchal paradigm within which the show is operating insists that one powerful woman is a delightful anomaly, but multiple powerful women are a threat to hegemony. By these standards, Buffy, by herself, is set up as a superior paragon of womanhood: strong, independent, sassy, beautiful, smart, courageous, and compassionate. If all women, however, were empowered like Buffy, or even a small group, it would be a subversive threat to male dominance, which is why Buffy and her power are exceptional and solitary. This, in effect, handicaps her, limiting her power.

Xander sexualizes power, instead of maintaining a respectful attitude towards strong women. He lusts for most of the powerful women he meets, good or bad – Buffy, preying mantis lady, Incan mummy, Willow (as she begins to mature), Cordelia, Faith, and Anya. At the same time, he finds himself at odds with this attraction, which manifests into this strange almost self-loathing that drives him to assert dominance. Since he’s a rather awkward boy without strength, he uses his tongue, throwing insults and off-the-mark opinions as “Xander, the Chronicler of Buffy’s Failures.”

YouTube Break: Buffyverse Season 3 Trailer

Joss Whedon’s writing for Willow’s dream is clever and filled with misdirection. Characters talk about Willow and her “secret,” a secret that she only seems comfortable discussing with Tara. Dream-Buffy constantly comments on Willow’s “costume,” telling her to change out of it because “everyone already knows.” We’re led to believe that Willow is afraid that her friends will judge her for being gay and being in a relationship with another woman…but this isn’t the case at all.

Instead, when Dream-Buffy rips off Willow’s costume, we see a version of Willow that is eerily reminiscent of season one Willow: a geek with pretensions of being cool.

But its strengths are strengths that none of the other big US dramas have. For one, the flexibility of its form meant that it could be any kind of show it wanted: one week it’s a goofy comedy, the next it’s a frightening fairy tale, the week after it’s an all-singing all-dancing musical. It was clearly the work of a team of writers, too, and when I was young and watching it for the first time it was the first time I really started to learn how TV was constructed – I got a thrill from seeing who had written each episode and guessing at what kind of episode it was going to be by who wrote it. Above all, though, the thing that Buffy has in spades that most shows lack, and the aspect of the show that season five best showcases, is emotion. Even at its most laid back, Buffy is a show spilling over with emotion, and it’s this that gives the potentially goofy premise of show its weight. Whedon et. al. were absolute masters at making us really care about their characters, and every audacious plot contrivance was easily swallowed when viewed through the lens of the real, human emotion that they would imbue it with.

I don’t want to get bogged down about how it sucks in a way that Buffy’s ability comes exclusively from superpowers. I get that, and I could write about it endlessly, but in this moment, I don’t care because Sophia doesn’t care. She watches Buffy and sees a woman who kicks ass, and she wants to emulate that. It’s tough to over-analyze and intellectualize a TV show when you’re watching a young girl practice roundhouse kicks because she wants to be a strong badass like Buffy the Vampire Slayer. And I have to say, it’s much more heartwarming to see her excited about becoming a strong woman with martial arts skills than it was to watch her pretend she couldn’t speak–because she wanted to be Ariel from The Little Mermaid.

YouTube Break: Buffyverse Season 4 Trailer

When the popular movie Twilight first appeared in theaters, it did not take long for fans of Buffy the Vampire Slayer (BtVS) to shame Twilight’s Edward with a fan video smackdown (“Buffy Vs. Edward”). The video shows Edward stalking Buffy and professing his undying love, with Buffy responding in sarcastic incredulity and staking Edward. While it may appear that this “remix” of the two characters was about Buffy slaying a juvenile upstart and reinforcing her status as the queen of the genre, there was more at stake, so to speak. Buffy slaying Edward says more about the perceived masculinity and virility of the vampire in question than about Buffy herself as an independent woman. Buffy was never given that much agency in her own show. Buffy’s lovers stalked her, lied to her, and often ignored her own wishes about their relationships all in the name of “protecting” her. Many of these things are what fans of BtVS pointed out as anti-woman flaws in the narrative of Twilight, yet Buffy did not stake the vampires who denied her agency in her own relationships; instead, she pined for them!

Equality Now: Joss Whedon’s Acceptance Speech by Stephanie Rogers

In 2007, the Warner Brothers production president, Jeff Robinov, announced that Warner Brothers would no longer make films with female leads.

A year before that announcement, Joss Whedon, the creator of such women-centric television shows as Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Firefly, and Dollhouse, accepted an award from Equality Now at the event, “On the Road to Equality: Honoring Men on the Front Lines.”

Watch as he answers the question, “Why do you always write such strong women characters?”

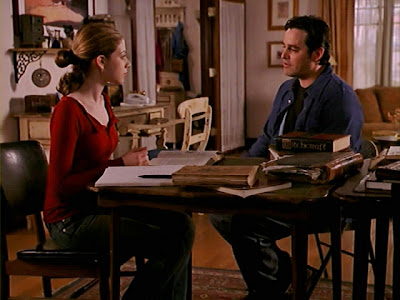

Xander Harris Has Masculinity Issues by Lady T

When I look at Xander through a feminist lens, I find him fascinating because he’s a mass of contradictions. He’s a would-be “man’s man” – obsessed with being manly – whose only close friends are women. He’s both a perpetrator and victim of sexual assault and/or violation of consent. He’s both attracted to and intimidated by strong women. He jokes about objectifying women and viewing sex as some sort of game, but in more intimate moments, seems to value romance and real connection. He’s a willing participant in the patriarchy and also a victim of it.

YouTube Break: Buffyverse Season 5 Trailer

YouTube Break: Buffyverse Season 6 Trailer

So whilst Buffy can defeat demons and save the world over and over, her emotional detachment and self-righteous sense of martyrdom (have some humility woman!) make these fights she doesn’t actually win, absolutely crucial to the Series’ greatness. Ultimately that’s why I find it hard not to let out a little yelp of glee when Dark Willow declares, “You really need to have every square inch of your ass kicked.” Faith, Willow and Anya teach Buffy to lose the ego and remember what she’s really fighting for, and that’s feminism in action right there.

A common criticism of Dawn is that she’s much more immature than the main characters were at the start of the series, when they were close to her in age (Dawn is introduced as a 14-year-old in the eighth grade; Buffy, Xander, and Willow were high school sophomores around age 15 or 16 in Season 1). Writer David Fury responds to this in his DVD commentary on the episode “Real Me,” saying that Dawn was originally conceived as around age 12 and aged up a few years after Michelle Trachtenberg was cast, but it took a while for him and the other writers to get the originally-conceived younger version of the character out of their brains. But I don’t need this excuse; I think it makes perfect narrative sense that Dawn comes across as more immature than our point-of-view characters were when they were younger. Who among us didn’t think of themselves as being just as smart and capable as grown-ups when we were teens? Who among us, when confronted with the next generation of teenagers ten years down the line, were not horrified by their blatant immaturity?

Willow is Whedon’s version of the answer to the underrepresented gay community. But, Willow appears to have had a healthy sexual relationship with her boyfriend Oz, and there is no hint at otherwise. She also pined for Xander for years. Both men. We see her gradually start a relationship with Tara, but she never talks about or reflects on her sexuality or coming out. We see that she is nervous about whether her friends approve. But, it doesn’t get much deeper than that. No characters have a deep conversation with her about her orientation. It’s not a thorough exploration. She goes from being with men to exclusively being with women and identifying as a lesbian. This is fine for Willow, but because there are really not many open gay or lesbian characters within the entire series we are dependent on her narrative alone.

YouTube Break: Buffyverse Season 7 Trailer

Strong Boy/Smart Girl: Another Hollywood Trope in ‘The Bourne Legacy’

Buffy the Vampire Slayer Week: Buffyverse Season 7 Trailer

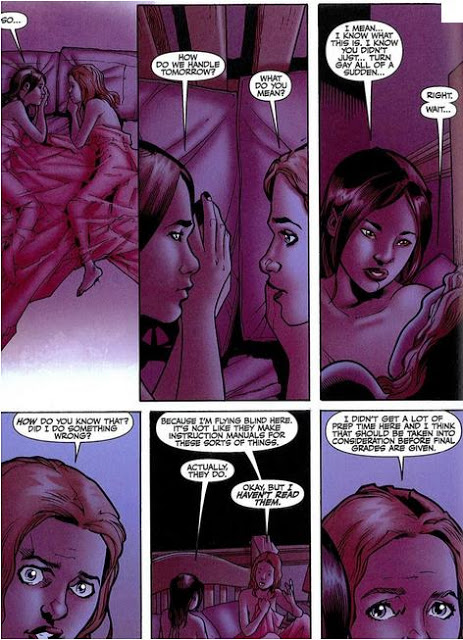

Buffy the Vampire Slayer Week: Whedon’s Binary Excludes Bisexuality

|

| Excerpt from season eight of Buffy the Vampire Slayer |

Buffy the Vampire Slayer Week: Defending Dawn Summers: From One Kid Sister to Another

|

| Michelle Trachtenberg as Dawn Summers |

|

| Dawn and Tara, fellow outsiders from the Scooby gang, pass time with a thumb war. |

|

| Dawn as annoying little sister. |

|

| Dawn in damsel-in-distress mode. |

|

| Dawn writes in her diary. |

|

| “It doesn’t matter where you came from, or how you got here, you are my sister.” |

|

| Dawn’s tantrum in Season 6’s “Older and Faraway” |

|

| Buffy and Dawn hug in “Grave” |

|

| Dawn with Buffy during her metaphorical rebirth in “Grave.” |

|

| Dawn lurks in the background as Buffy gives a speech to potential slayers. |

|

| Xander has a heart-to-heart with Dawn |

|

| Dawn accepts her humanity and finds her maturity. |

Buffy the Vampire Slayer Week: Why Faith, Anya, and Willow Beat Buffy

|

| The cast of Buffy the Vampire Slayer |

At the end of my first 45 minutes with Sunnydale’s finest, I remember feeling absolute delight. On the promise that they be returned in perfect condition, I borrowed one series after another of my friend’s treasured DVD boxsets, handed over with warnings and reverence, and received with the desperation of an addict. Needless to say I watched nothing but Buffy until reaching the final episode of Season 7 (it didn’t take long). I love this show. I believe it to be one of the most important television shows that has ever been conceived. Yes, there is the Riley blip, and Tara is no natural Scooby, despite her witchy credentials. But out of 144 episodes – that’s almost 7 days of watching Buffy continuously for 16 hours a day* (you’ve got to sleep right) – these niggles are small. It is a work of genius, and I will argue violently against any dissenters.

And yet … I am not particularly a fan of Buffy herself. I’m always on her side when she’s facing the bad guys, whether it’s The Master, Mayor Wilkins, Glory or the downright terrifying Caleb. But when it’s Willow, Faith or Anya that Buffy’s fighting, I can’t help feeling she sort of has it coming.

The entire show champions under-dogs: the nerdy, the quirky, and the excluded. People who aren’t classically beautiful; the unpopular ones that you’re embarrassed to hang out with; the screw-ups and lost souls. And with her perfect hair, kick-ass fighting skills, cool outfits, and dangerously sexy boyfriends, Buffy just doesn’t evoke the empathy of some of her fellow Scoobies. Sure, she has some romantic tangles along the way (excuse the enormous understatement), and definitely messes up occasionally: trying to kill her friends and sister; running away to leave Sunnydale to certain destruction; dying – all notable examples. But when it comes to saving the world, she delivers. She’s awesome at her job. And boy does she know it.

|

| Faith, Buffy’s “rival” slayer |

So when Faith arrives and ends up rocking Buffy’s world, there’s a wonderful satisfaction in watching the pair battle it out. Unpredictable, sexy and wild, Faith personifies the dark side of Buffy: what she could have been if she wasn’t so annoyingly right all the time. But more than that, Faith’s psychological issues make her empathetic: her psychotic behaviour is not only understandable, but almost forgivable. From an unstable and implied abandoned background, Faith openly wishes for the wholesome simplicity Buffy’s life retains despite her Slayer responsibilities. She has a touchingly childlike desperation for the conventional stability that the Scoobies, Giles, Angel and Joyce provide for Buffy. The Mayor’s fatherly affection for Faith appears the only stable relationship she has ever come across, where she is treated like the innocent little girl she seems to have never been allowed to be. It is no wonder that she would do anything for him: wouldn’t most of us do anything for our family after all?

Faith is an emotional Slayer, and it is not a straightforward job for her – she is driven by instinct, pain and desperation, and pushes Buffy further than any of her other adversaries up until that point. When Buffy stabs her at the end of their final confrontation in Season 3, she commits the very action that she condemned Faith for. That Faith survives is the only thing which saves Buffy from a hypocrisy that will stalk her in further conflicts.

But when it comes to Buffy’s hypocrisy and double-standards, no situation makes them clearer than the moment she all too easily decides she has to kill Anya in Season 7’s “Selfless.” Being a bad-ass Vengeance Demon notorious across numerous hell dimensions, Anya is nowhere near as harmless as the bunnies she has an illogical phobia of. Her confrontation with Buffy is vicious, and bloody, and is without a doubt one fight we’re really not rooting for Buffy to win.

|

| Vengeance Demon Anya |

Anya’s devastation after being jilted at the altar by Xander guts her emotionally. When she renews her status as a Vengeance Demon, it’s driven by desolation and grief. Like a lost soul she is doomed to meander through Sunnydale with no sense of purpose after her excruciating break-up with the love of her life, and finally resorts to her work as her only source of pride and fulfilment. The fact that that happens to include administering gory punishment to insensitive frat boys serves first to show the ravages her soul has endured – but subsequently her compassion when she bargains for them to be brought back to life.

Similarly Xander is all too aware of how painful the repercussions of his commitment-phobia are, and pleads with Buffy not to kill his one true love. When Buffy tells him she faced this problem when she stabbed Angel way back in Season 2, I can’t be the only one that felt she had milked that drama one time too many! And here’s why … To compare that relationship with Xander and Anya’s is immature at best, and delusional at worst. Xander and Anya move in together. They get engaged. They profess their love for one another openly. They plan to have children. They can spend whole days together without apocalypse as an excuse. And most importantly of all, they have lots and lots of sex.

Their physical connection, their delight in carnal intimacy, their inappropriate lustful outbursts are demonstrations that Anya and Xander are a grown-up couple. To compare the adult subtleties of the way they relate to one another with the doomed fairytale of Buffy’s teenage love affair shows a complete lack of empathy and understanding on Buffy’s part. She has no idea what it is like to experience love of the kind Anya and Xander share: where it isn’t “end-of-the-world” urgency all the time! Her response to Xander’s pleas with, “I am the law,” before leaving to kill fellow Scooby, Anya, out of some presumed sense of morality simply reeks of arrogance.

Thankfully, Anya survives Buffy’s assault, and in doing so she gives her a glimmer of insight into the lengths love, and not responsibility, will drive a person to. Amazing that after the show’s most exhilarating confrontation of all, she’d need a reminder of that, but it’s a lesson Buffy clearly doesn’t learn easily.

Buffy vs Willow: replacing “and” with “vs” surely never had a more devastatingly exciting depiction onscreen!

As one of the most popular characters, and with an incredibly complex character arc, Willow is arguably the reason why I love this show so much! Endlessly patient and studious throughout Seasons 1 and 2, over time Willow transforms into the embodiment of the “Woman Scorned” becoming a murderous and merciless master of dark magic in Season 6. In this gothic incarnation of unrestrained power Willow expresses all the suppressed frustrations she’s endured as Buffy’s “sideman.” She flaunts her strength, exhibits her magical prowess and becomes the personification of her enraged emotions. There’s a cathartic thrill at seeing someone previously so meek rebel. Countless times over numerous episodes we watch Willow put her own dramas to one side to prioritise Buffy’s needs, but with the death of Willow’s soul-mate she finally lets her instincts take over. Right or wrong lose significance and at last, Willow’s emotional needs are given priority – that she almost destroys the world in the process doesn’t say much for Buffy’s ability to empathise with her dearest friends!

|

| Dark Willow |

So whilst Buffy can defeat demons and save the world over and over, her emotional detachment and self-righteous sense of martyrdom (have some humility woman!) make these fights she doesn’t actually win, absolutely crucial to the Series’ greatness. Ultimately that’s why I find it hard not to let out a little yelp of glee when Dark Willow declares, “You really need to have every square inch of your ass kicked.” Faith, Willow and Anya teach Buffy to lose the ego and remember what she’s really fighting for, and that’s feminism in action right there.

*I am no mathematician, and it is testament to my love for Buffy that I actually worked this out.

———-