|

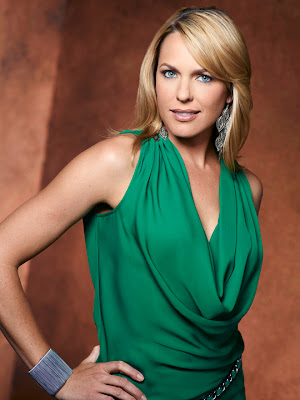

| Emilia Clarke as Daenerys in Game of Thrones |

Written by Megan Kearns for our Infertility, Miscarriage and Infant Loss Week. | Warning: Spoilers ahead!

When I first wrote about Game of Thrones two years ago, I wrote about its vacillation between showcasing strong, intelligent female characters and its sexist objectification and misogynistic rape culture.

I received an exorbitant amount of comments on my criticism of the show — even though I simultaneously lauded its brilliant acting and interesting characters and dialogue. Some told me I didn’t understand anything about the show. Others told me to wait, just wait as it would get better. While the show suffers serious problems, particularly in its sexposition and depiction of graphic female nudity, as the show has progressed, it has indeed become more and more feminist.

We witness more of the women expressing their disdain for their lot in life due to their gender. We see women buck gender norms (Arya, Brienne, Yara Greyjoy) and we see women scheme to surreptitiously assert their power (Margaery Tyrell, Cersei Lannister, Olenna Redwyne) or even just to better their lot in life (Shae, Ros, Sansa).

While many women orchestrate machinations behind the scenes, no woman is openly a leader, boldly challenging patriarchy to rule. Except for one. Daenerys Stormborn of House Targaryen.

When I first wrote about Dany (Emilia Clarke), I was captivated by her. She drew me in immediately and became my favorite character. I loved watching her transformation from meek and timid, bullied by her creepy brother Viserys, to a powerful yet kind-hearted Khaleesi (Queen). Each episode she grows more bold and assertive. Yet she continually strives to be fair and just. Watching her growth has been the most enjoyable aspect of the series.

Daenerys marries Khal Drogo in an arranged marriage in order to secure Viserys, rightful heir to the Iron Throne after the murder of their father the king, an army so he can claim the throne. Viserys uses Dany, telling her he would have all 40,000 Dothraki rape her if it garnered him an army. Nice guy.

After a rapey wedding night (Sorrynotsorry, fans. It is), Daenerys and Drogo eventually form a bond and fall in love with one another. (I know, I know, but bare with me). Dany grows more confident and assertive both with her sexuality and her authoritativeness in giving the khalasar (clan or tribe) commands. Months later, when Viserys hits her, she hits him back and tells him if he strikes her again, she will have his hands cut off.

When Dany becomes pregnant with a son, she eventually convinces her husband to cross the sea, something the Dothraki fear, in order to claim the Iron Throne and rule. Both Daenerys and Drogo believe their son Rhaego will be the heir to the throne, calling him the “Stallion Who Mounts the World,” because according to a Dothraki prophecy he will be a great khal (king) of khals, uniting the Dothraki as one khalasar (clan or tribe) and conquer the world.

|

| Game of Thrones |

After Khal Drogo’s khalasar conquer a village, Daenerys — growing more confident and outspoken — prevents the men from raping the enslaved women. When challenged by her husband, she boldly defends her decision, trying to advocate for the women’s rights. Rather than crediting his wife’s penchant for advocacy, Drogo tells her she grows fierce as their son grows in her womb, “filling her with fire.”

But after her husband has a wound, Mirri Maz Duur an enslaved shaman whose life Dany spares, treats his injury. Yet he falls deathly ill. Mirri tells Dany how to save him, by using blood magic, something forbidden by the Dothraki. Dany follows her instructions. Yet she goes into labor and passes out. When Dany awakens, her advisor Jorah tells her that her son was born dead and deformed with scales. She’s been “rewarded” by having Drogo a shell of his former self in a catatonic state. When Dany confronts the shaman, asking when she will be reunited with her husband, Mirri replies:

“When the sun rises in the west and sets in the east. When the seas go dry and mountains blow in the wind like leaves. When your womb quickens again, and you bear a living child. Then he will return, and not before.”

Mirri’s spell took the life of Daenerys’ unborn son as revenge for the Dothraki attack on her village. Also inherent is an infertility curse, that Dany will not have any of her own children. She loses the lives of both her husband and her unborn child.

With nothing left to lose, Daenerys resolves to make a bold and drastic decision which showcases her resolve and empowerment. As Angela Smith wrote on bereaved mothers at Bitch Flicks:

“It’s not uncommon for women to feel empowered to make drastic changes after losing a child. They may, understandably, become far less tolerant of others due to the realization nobody at all can break them down any further than they’ve already been broken.”

Dany has one of her Khalasaar place 3 dragon eggs she was given as a wedding present on the pyre. As the fire burns, she steps into the flames, despite the protestations of Jorah. In the morning, a new day has dawned. Dany emerges from the ashes unharmed, and the eggs have hatched with the 3 dragons perched on her body.

|

| Daenerys becomes the Mother of Dragons |

But now that she has lost her son, Daenerys decides she will take the Iron Throne herself and rule the Seven Kingdoms. After all the men in her life — her husband, son and brother — have died, she claims the throne for her own.

Dany becomes the metaphorical phoenix rising from the ashes, purging the last vestiges of her former timidity to transition into her life as a powerful leader.

At the end of season one, I’ll admit I worried that her magical powers were somehow explaining away her awesomeness. But now I see that no, it’s merely to highlight the importance of her role in Game of Thrones — as a woman leader challenging sexism.

Daenerys is continually called the Mother of Dragons, spoken with awe and reverence. In many cases, women are allowed to lead or be ruthless as lioness mothers. And while Dany lost her son, and she may be cursed with infertility by Mirri, she still remains a mother figure. She envisions herself as the mother to her 3 dragons. In the second season’s episode “Prince of Winterfell,” Dany’s dragons are kidnapped in the city of Qarth. When Jorah tells her to abandon them, that they are not her children, and escape, Dany replies:

“A mother does not flee without her children…They are my children, and they are the only children I will everhave.”

Daenerys risks her life to save her dragons, and they save her life and free her when she’s captured as well. The mysterious masked woman Quaithe tells Jorah that “dragons are fire made flesh…and fire is power.” Daenerys has given birth to power. Power contains a duality – it can subjugate and torment or it can crush oppression and yield justice.

Speaking with confident assuredness, Daenerys tells those that doubt her:

“When my dragons are grown, we will take back what was stolen from me and destroy those who have wronged me! We will lay waste to armies and burn cities to the ground!…I will take what is mine, with fire and blood!”

In season 3, after having survived the treacheries in the city of Qarth, Daenerys looks to procure an army in the city of Astapor in order to take the Iron Throne. Despite her steeliness, she has not lost her kindness. She tries to give water to a dying slave. She doesn’t hide her horror and disgust during negotiations when she hears that murdering a newborn in front of the infant’s mother is a component of the training for the highly skilled slave warriors, the Unsullied. To her advisors, she expresses her unease over buying slaves for an army. She doesn’t want the “blood of innocents” on her hands.

|

| Daenerys with advisors Ser Jorah Mormont and Ser Barristan Selmy |

In last week’s episode “And Now His Watch Is Ended,” Game of Thrones turned a corner in perhaps the most feminist episode of the series.

Daenerys makes a trade for all 8,000 Unsullied warriors, appearing as if she’s going to give up her dragon Drogon to make the exchange. But it’s all a ruse. When the brutal slaver Kraznys — who has insulted Dany with sexist, slut-shaming insults, erroneously thinking she didn’t understand the Valeryian language — is irritated that her dragon doesn’t obey him, she retorts that of course he doesn’t, “a dragon is a not a slave.” Dany then orders the Unsullied, now in her command, to murder the slavers and break the chains off the slaves. She frees the enslaved warriors, asking them to fight for her as free men. Daenerys then drops the whip equating ownership of the slaves. In essence, she drops the symbolic weapon of tyranny and oppression, heralding rebellion.

If there was ever any question, Daenerys is clearly here to dismantle the patriarchy.

Not only is she a woman leader, her very existence challenging the status quo. But Daenerys openly questions and challenges patriarchal norms. She refuses to abide by societal gender limitations mandating men must rule. She’s determined to forge a different path. Rather than follow in the footsteps of leaders embodying toxic masculinity, she’s determined to rule through respect, kindness and fairness — not through intimidation or fear. Daenerys refuses to enslave people. She wants to emancipate them.

The Mother of Dragons cares for the dragons as if they were her own babies. Could it be that Daenerys will become the archetypal mother of humanity? Perhaps. She’s wielding justice, crushing oppression and protecting the weak. Yet it is the loss of her son that enables Daenerys to envision herself in the role of leader. No longer is she supporting a man to be a great leader. She has become that leader.

The princess has become a queen.

|

| Dany being a badass. Boom. |