|

| Welcome to Twin Peaks. |

This is a guest post by Cynthia Arrieu-King and Stephanie Cawley.

Cynthia’s take:

Why do I like Twin Peaks?

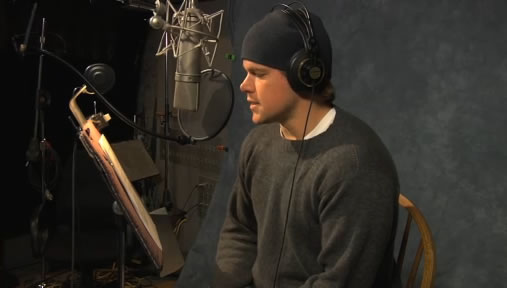

I remember dialing through Netflix Streaming back in May of this year as a way of breaking up the cooking of several chopping-intensive dishes. The show was totally unappealing to me when it came out and I was in high school. But this year, for the first three episodes or so, I could take it or leave it: adultery and hysterics and murder with the occasional bright spots of Dale Cooper being absurdly smug about the quality of cherry pie.

Slowly I paid more attention to the idea of intuition present in Cooper’s scenes. I felt more indifference about its postmodern sorta-for-real, sorta-not simulacra qualities: fifties diners, women who all wear bright lipstick and clingy sweaters, a revolving door of high school types, baddies and inscrutable parents.

Then, I saw the clip in which Agent Cooper dreams he is old, a little person talks to him backwards in a red room (redrum! redrum!) as does Laura Palmer who then whispers the name of her killer in his ear.

What.

And by the light of the next day, Cooper makes everyone go out in the middle of the woods, whispers the name of each murder suspect to a successive series of rocks in his hand and well, I’m not going to say more, but I was like what kind of bizarre Jungian Joseph Campbell version of the Trickster versus the Intuition is going on here?

I love these parts but the over-the-top violence constantly involving the women characters wore on me. Because even as satire, Twin Peaks always asks you to recognize that if not at that moment, you once felt real emotion for characters like this, you fell for it, and it is nakedly pushing those emotional sexual violence id buttons to their unbearably absurd extremes, then splashing the cold water of flip logic and optimism in your face.

And over and over until about the beginning of the second season, I felt an edge of incredulity in myself: How could this have been on network television? How in the world did this happen?

What did you like about it Stephanie?

Stephanie’s take:

What do I like about Twin Peaks? The Log Lady, the stoplight, the giant and the room service guy who brings Cooper his milk, every second of Angelo Badalamenti’s walking double bass, when Lucy says, “most of his behavior was asinine,” Ben and Jerry Horn stuffing their faces full of brie sandwiches, Audrey Horn’s saddle shoes, Nadine’s glorious silent drape runners, my unflagging belief in Agent Cooper. So many strange, wonderful things to marvel at in this show! You hit some of my favorite scenes, and the scenes that most stuck out to me on my second time through the show: the donut table at the stone-throwing divination and the first dream in the Black Lodge.

What I love about Twin Peaks, and Lynch in general, is his strange intensity and earnestness. What you called “postmodern sorta-for-real, sorta-not simulacra qualities” I actually see as Lynch making some kind of weirdly authentic invocation of the past or a spiritual core of America through the kitschy trappings of Twin Peaks. I don’t think that Lynch sees cherry pie and creamed corn and prom queens as truly “good” or the “true America,” the way that politicians might conjure apple pie and pick-up trucks to signify some idealized version of America. But I think Lynch uses these images and stock characters as potent cultural symbols that he can shuffle and reconfigure, but that carry strong psychological and cultural associations. As you said, I think that Lynch really is trying to wrestle with good and evil with Twin Peaks, using these cultural signifiers, and this is something I kind of love about it, even if it gets messy and maybe fails at making any kind of coherent statement.

Though it seems strange to say, another thing that I like about Twin Peaks is that the violence is actually visceral and horrible. Lynch takes these symbols, especially the prom queen girl-next-door All-American sweetheart and perverts them to the extreme. As you say, “it is nakedly pushing those emotional sexual violence id buttons to their unbearably absurd extremes,” though I would also argue that the violence is of a very different quality from so much other violence in contemporary movies or TV shows.

Violence in Twin Peaks is delivered in a way that is emotional and intense, not so much about cheap bait-and-switch jumpiness or the porno gore splatter, but the horror of the moment of the attack. The horror of violence as an action, as a depraved tunnel that swallows up everything we like about the world. We get so much of humanity being bright and good in Twin Peaks—Cooper, Harry, Andy, Lucy, etc.—but we are also forced to witness and even participate in the spectacle of unspeakable violence.

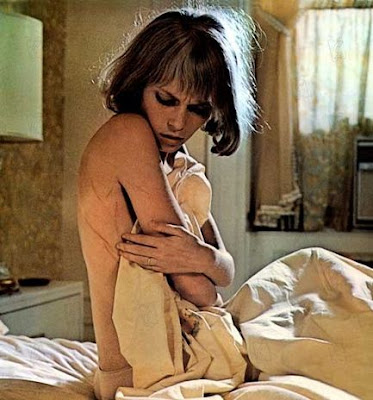

(Spoiler alert) The scene when Leland/Bob kills Maddy is one of the most intense sequences I’ve ever seen on little or big screen. The clicking of the record player, Sarah Palmer’s bony hands, the glare of the lights as Maddy and Leland/Bob wrestle, their slow-mo distorted voices. My stomach is clenching just thinking about it. This scene is vivid and visceral, very different from the many horror movies or TV crime shows in which bodies, especially women’s bodies, are violated and disposed of with ease, with almost a wink to the viewer. I think that through scenes like this Lynch forces the viewers to confront violence in a serious way and thus to identify more thoroughly with its victims.

Of course, the victims are mostly women. In fact, violence against women is literally at the core of Twin Peaks. I’m not sure what my question to you is, but this is the thing I am trying to figure out—what to say about all the dead and victimized women?

Cynthia’s take:

What to say. What to say. So much victimization. So many women! I agree that Maddy’s murder is the worst violence I’ve ever seen in television or a movie. And I agree that it’s at the core of the story, and different in its tone than almost any other kind of violence against women in television. There’s no wink, as you say. But I think I read the good and evil in a different way than you do and the more I talk to people about Twin Peaks, the more it feels as if the show’s violence gets taken several ways depending on the viewer.

I like all the good characters, so to speak, they are bright, but they don’t risk pure earnestness. They all have a crazy quirk to balance out the sincerity. Nadine’s insane eye-patch and youth. Andy’s inappropriate weeping. Cooper’s hanging upside down in his gravity boots while he dictates notes. It could be delight in life, it could be Lynch’s wish to burden us with quippy or awful silences. I can’t help but like this, but at the same time, it’s part of a problematic equation: The killer gets to say, “It was Bob who made me do it,” and can say he’s not responsible for any of this violence. Oops, he didn’t mean it, and in the world of demon possession, well, he’s telling the truth. No one is responsible for the murder of women. We dads just can’t help it and we’re inconsolable too.

I read this scene when the killer is in prison as a way for Lynch to be responsible, to critique this hands-off, “the devil made me do it” stance so prevalent in the way America does, well, everything. In a system of good and evil, it’s powerful that this (spoiler alert) is the close relative of the murder victim. But then my friend Kyle Thompson said, “No, no, no, it’s an apology, it’s not a critique.”

And I would say that he, as a man, may have a way of reading all of these shuffled signs (I love that you said that) in a way we do not and could not.

Since it is pretty much the worst violence, the most operatic violence towards women I’ve ever seen, in the end I suppose all the dead and victimized women are the thing that kept me from not entirely liking the show up until I realized the show was about intuition, good and evil as you said in a way nothing else was. Twin Peaks flies in the face of our culture in so many ways it’s hard not to want to go apologist for Lynch’s apology. Which isn’t where I want to be. You’re right, it doesn’t have the kind of moral note that stems from sentimentalizing those we oppress – the wink – another-body-in-the-bank-attitude. It’s not network television crime show violence, though I feel it has some hem of magazine shows about murdered women in it, the way it wants to invoke gossip and pity with an old trope, familiar people, manufactured sensationalism. What’s important to me is that Lynch is saying, this is what it looks like close up.

I’ve met so many people who feel this is the best thing they ever saw on television. How accessible do you think the satiric aspect is for yourself or for anyone? Like Mad Men, I wondered if Twin Peaks re-inscribed racist/sexist notions until it started simultaneously to treat violence as serious and mocking us and soap opera for how enthralled we are by story.

It’s the 20th anniversary of Twin Peaks. Why does it still work?

Stephanie’s take:

I am really not sure about how accessible the satiric aspect of

Twin Peaks is to today’s viewers, myself included, because of the current TV/media climate. So much TV today, especially reality TV, has this bizarre tone that is slightly self-mocking but is simultaneously dead serious about its extravagance. This is actually kind of similar to the tone of

Twin Peaks, but I don’t think it’s that intentional or meaningful today. And I don’t even know if the general audience reads this kind of tone as satire, or as a particular form of humor, or if they just read it straight. After all, there are apparently

conservatives who seriously believe Stephen Colbert is on their side, and there is a website of screencaps of people posting

The Onion articles on Facebook and

commenting as if they were serious news. And I sometimes find myself having to explain to my high school-aged students that the word “literally” does not mean “figuratively.” What I’m saying is basically that I don’t really know, but that today’s viewers might either be better or worse equipped to navigate the slippery nature of

Twin Peaks, I just don’t know which!

I think you’re definitely right that Twin Peaks is wide open for many interpretations, and I want to be able to read the killer revelation as a critique, but I just don’t think that it is. I similarly want to be able to read all the gender imbalance in the Twin Peaks landscape as a critique because I really do love so much about it, but I just can’t find enough to back me up on that reading at all. I just don’t think Lynch was thinking about gender that seriously.

We have both admitted to fondness for the more fringe female characters like the Log Lady, Nadine, and Lucy, but they, and all the other women, really only exist according to their relationships with men. We find out the Log Lady, holder of mystical truths and wearer of incredible flannels, is a kind of Miss Havesham, that she only is the way she is because her husband died on their wedding night. Similarly, Nadine is the way she is—batty and amnesiac and eye-patched—because of husband Ed. And all of Lucy’s energy gets sucked up into a boring pregnancy and paternity subplot, though her pluckiness does seem to exist regardless of her poor taste in men-who-are-not-Andy.

And the list continues. Audrey’s character arc consists of her moving from virgin with daddy issues to non-virgin with slightly different daddy issues. Donna does some intrepid sleuth-work, but spends most of her time dealing with her sappy relationship with James. Maybe only Katherine can be said to have a personality and take actions that are not based around her relationships with men, but her wiliness really depends on her ability to use sex as a form of manipulation.

Meanwhile, Agent Cooper and Harry and Ed get to go out and fight for all that is righteous (though they also all have love lives), and Windham Earl and Leo and Ben Horn get to be menacing and threatening and powerful. Even Leland gets to be infected by demons at least! I would like it so much if any of the female characters were at least worthy of demon possession.

At the risk of sounding like feminist criticism is about score-keeping or, as you said, playing apologist for Lynch, I think I could sort of “forgive” the horrific violence against women if the women characters were actually fully drawn and able to participate in the storylines in an equal way to the men. Since you bring it up, I think this is how Mad Men succeeds (though not with regards to its handling of race, ugh) in depicting a brutally sexist world and some seriously misogynistic characters in a way that is not sexist or misogynistic itself.

That said, I still pretty much love Twin Peaks. My boyfriend and I affectionately dubbed our apartment “The Great Lodge” because it has 70s wood-paneled walls, a fireplace, and is surrounded by pine trees. The Log Lady was my Facebook profile picture for a while. But fangirlishness aside, I’ve watched a lot of TV shows and I’m hard pressed to think of any that are as interesting and strange and ambitious as Twin Peaks.

But I think part of its allure is also in its unfinished-ness. Shows that are canceled unjustly in the eyes of their fans gain a kind of cult following and fervor they might not otherwise have if they were allowed to run their course and possibly collapse or devolve into sloppiness or repetition. Many of these shows, Twin Peaks included, are legitimately brilliant, but still benefit from the extra glory that our culture loves to tack on to things (or people!) that come to an untimely end. So, when we think about Twin Peaks, we necessarily think of the disappointing and horrifying and thrilling lack of closure at its end.

Cynthia’s take:

I can’t believe there’s five years of Mad Men and only two of Twin Peaks. Argh.

I like what you’re saying about the degree of gender critique in Lynch. It’s kind of like when my former classmate Kirk Boyle saw Dead Man by Jim Jarmusch and couldn’t read the cultural critique in it – Is it about Clinton? he asked me once. I was struck by how we can look for these systems of meaning out of habit and it makes me wonder right this second if there’s some blind spot in this. It seemed the movie was about a good death, lawlessness in the American vein, and immortality and that can be undetectable to an eye looking for allegory. Maybe allegory is the case here.

I agree with you about the little power of the women in this show, their silly or violent struggle. But I’m not on the same page with you about Audrey Horne. She does some pretty unbelievably audacious moral acts. She looks for Laura’s killer when in fact she had no deep friendship with Laura. She just knows something’s afoot with her father and the murder so she sleuths her way into being hired at the brothel—looking pretty fierce until the moment her father knocks at her door and she’s in a teddy ready for sex work. And doing better work in some ways than Cooper. She takes over her dad’s business by sheer will, but not after clearing out the entire meeting of Scandinavian investors by moping slyly about her sadness at the violence. She liked undermining her dad so that he would pay attention to her power, and in the end saved his business (and notably, threw off Bobby’s advances so matter-of-factly). To me she represents an m.o. something like, “We’re all playing a role in a power-play; at least I’m choosing my role and making it work for me.”

I guess my final word on the series would be that I like how Lynch holds a serious mirror up to our faces about how much we look for the violence and what it really is like. What’s your final read?

Stephanie’s take:

I still haven’t seen Dead Man and I feel like you’ve mentioned it to me before! In my queue. Anyway.

I do think I was being a bit reductive in my characterization of Audrey. She is one of my favorite characters and that scene in the brothel is one of the most unsettling scenes of the show (and on a show that is deeply unsettling so often, that is saying something). I guess I’m just a little hung up on what happens with her storyline with the rich guy in the late second season. But I think I’d prefer to pretend that much of what happens in the late second season doesn’t really happen.

To me, one of the testaments to Twin Peaks‘ greatness is that we’ve had this long exchange about it and could probably still keep going. More than once, I have found myself writing in big, aimless circles when trying to articulate what I think. The show can be read so many different ways, and as you’ve noted, it seems that everyone can bring their own particular interests and concerns to bear upon the show. It fails to resolve neatly, but I think this is what makes it so intriguing, so worth watching and then talking about. For all the interesting, quality TV shows we get to watch today, there is still nothing, to me, that is quite like Twin Peaks.

My last words on Twin Peaks? Everyone should watch it and then invite me to Twin Peaks-themed murder-mystery dinner parties. I’ll bring the cherry pie.

Cynthia Arrieu-King lives near Atlantic City but her cat Kenny lives in Louisville, Kentucky. She writes poetry and grades a lot of papers. On Sundays at 11AM you can hear her and Stockton students Jenna McCoy and Laura Alexander do a talk show about local and visiting writers,The Last Word, at WLFR FM Lake Fred Radio wlfr.fm.

Stephanie Cawley lives in Philadelphia with her cat, Vincent van Gogh. She writes poetry and reads a lot of comics.