The rest of the movie takes place in the canyon–a claustrophobic nightmare that only works because Franco is apparently an amazing actor–and inside Franco’s mind, through flashbacks of his super hot (gasp) blond ex-girlfriend and the phone calls from his mom and sister that he clearly stupidly ignored prior to his departure. He also hallucinates some crazy shit, like a giant Scooby-Doo blowup doll that’s soundtracked to that ghoulish laughter reminiscent of the last few seconds of Thriller. Yeah! And though it sounds absolutely insane, it’s why the film works. Boyle takes a narrative about a guy struggling to get out of a hole and turns it into an action film, a radio show, a documentary, a commercial, a disaster movie, a cartoon, and a comedy. About a guy struggling to get out of a hole.

Not that there aren’t a few impossible-to-deal-with moments. The final scene, which is poignant enough on its own, insists on beating the audience over the head with its call to EXPERIENCE EMOTION, courtesy of this ridiculous Dido & A.R. Rahman song. And I still can’t quite figure out how the closeup shots of ice-encased Gatorade and Mountain Dew add anything more than advertising revenue, as much as I’d like to argue that, “If I were trapped in a cave, about to die, drinking my own urine, toying with the idea of amputating a limb, I’d totally hallucinate all these brand-name beverages from Pepsico.”

And yes, god, seriously, The Women. I know this is a movie about Ralston’s journey. I respect that and enjoyed watching the innovative ways Boyle used split screens, reverse zooms, fantastical elements, warped focus, and speed variations to tell Ralston’s story in a way I can’t imagine another director successfully telling it. That doesn’t mean I could ignore my own cringing every time a woman entered the frame. The ex-girlfriend clearly serves as a vehicle to show Ralston’s loner-ness; see, he pushed her away all cliche-like. We know this because she says Very Important Things to him. “You’re going to be so lonely,” she yells, after he silently (but with his eyes!) asks her to leave a sporting event they’re attending. (I want to say hockey?)

His hallucinations suck, too. His sister shows up in a wedding dress. His sister showing up in a wedding dress clearly serves as a vehicle to make us feel bad that he’ll be missing Very Important Life Events if he dies, like his sister’s wedding. More pointlessly, the hallucinated sister, who might have one speaking line if I’m being generous, is played by Lizzy Caplan, an actress who’s had large roles in True Blood, Party Down, Hot Tub Time Machine, Cloverfield, and Mean Girls. Instead of engaging with the film, I found myself taken completely out of it, as I wondered why they would cast an actress who’s clearly got more skills than standing in a wedding dress, looking sullen and disappointed, to stand in a wedding dress looking sullen and disappointed.

So, the first two women (the lost ones) show Ralston’s carefree coolness. The ex-girlfriend illustrates Ralston’s darkness and his need for independence–as do the voicemails he ignores from his mother and sister, which are played in flashback. His sister reminds the audience that Ralston has Things to Live For. Hell, Ralston even tries to console his mother in advance (when he records his deathbed goodbye with his video cam) by saying things like, “Don’t feel bad about buying me such cheap, crappy mountain climbing equipment Mom … I mean, how were you supposed to know this would happen!” Hehe. What? Apparently it’s easier to use every possible cliche ever of how men and women interact (as a way to reveal information about the hero’s personality and psyche) than it is to, I don’t know, show him interacting with some guys? Have him flashback-interact with Dad? Nope, we get Lost Women in Need, Wedding Dresses, and Mommy Blaming. And I haven’t even gotten to the masturbation scene yet.

[This is your Spoiler Alert.]

I struggled with the masturbation scene. Because it’s a failed masturbation scene. I mean, it’s a scene where masturbation is attempted unsuccessfully. I didn’t like that he took out his video camera and freeze-framed and zoomed in on a woman’s breasts from earlier–as far as I’m concerned, there’s no other way to look at that than as classic Objectification (and dismemberment) of Women. (Also, the audience laughed, and I was taken out of the film yet again.) But at the same time … whoa. Ralston knows he’s about to die. He’s out of water. He’s got no hope of being rescued. Ultimately, masturbation for him is an act of desperation, the desire to feel something that his body has already let go of. Yes–it’s powerful stuff. Watching Ralston’s body betray him shows his imminent physical death.

But it felt too much like The Ultimate Betrayal. As much as I sympathized with Ralston–and Franco is brilliant in this scene–I don’t want to let the film off the hook entirely. I mean, what’s with men and their dicks? If I’m trapped down there, I’m thinking, “A little less masturbation, a little more amputation.” Honestly. The scene played too much like a metaphor for his final loss of power (read: masculinity), as impotence usually does on-screen. In that moment, I no longer identified with the film’s initial overarching theme of hope and possible redemption; I just thought, “Oh man, he can’t get it up it. SNAP.” I guess I’m just wondering if the film really needed to go there …

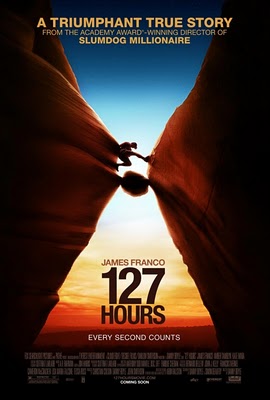

So, aside from the women “characters” being cliched, pointless, slightly offensive insertions used only to further our understanding of Ralston, 127 Hours is a fabulous film. I’m not even being sarcastic. I’ve never been much of a Franco fan–I mean, apparently he’s teaching a class about himself now?–but this performance is a game-changer for James and me. Boyle certainly showed his directing chops, too; this movie goes places a viewer would never expect–in fact, I don’t think I’ve ever seen anything like it. I cried. I eye-rolled. I looked away (often). And I laughed. Especially at the end of the film, when the woman behind me said, “Wait. You mean that shit was a true story?!”