For years, we have lived in a society that requires the majority of its female actors to have ridiculously impeccable bodies if they want to get work while their male counterparts are allowed to age normally, adding a few pounds to their waistline every few years. In fact, it’s highly unusual to see male actors have to answer for their weight and—more often than not—only the opposite occurs.

|

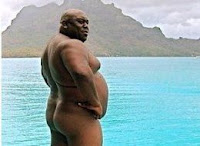

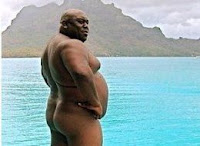

| Actor Faizon Love as Shane |

There are NUMEROUS examples of this phenomenon—Jack Nicholson, Alec Baldwin, Dustin Hoffman, Vince Vaughn, Al Pacino, Robert Deniro, even the recently filled out Jimmy Smits. But you’d be hard-pressed to name five female actors who have put on the pounds and continued to work.

Yes, Meryl Streep is not as slim as she was thirty years ago, but she certainly doesn’t have a bulging stomach like these men do. Her stomach is, in fact, quite fit. And the fact that she’s as tall as she is and wears a size fourteen tells me that you probably can’t pinch more than an inch around her middle.

Not only is this phenomenon made obvious by looking at these actors, it’s also made obvious by considering the television shows and films in our cultural zeitgeist: Knocked Up, The Break-up, King of Queens, Still Standing, According to Jim, Seinfeld, Frasier, and the list goes on.

This issue has bothered me for quite some time, but it really came to a head for me when I saw

Couples Retreat

on video recently (a movie that is so inane, unfortunately, I can’t recommend it). And, as it turns out, there is a scene in this movie that perfectly embodies this double standard (while also failing Bechdel with a vengeance usually only reserved for movies with only one major female celebrity), and I want to talk more about that scene today—as well as illustrate it—because it is, in fact, so egregious.

If you haven’t seen the movie, it’s about four couples that decide to go on an island retreat to improve their marriages. One of the couples is considering divorce, and their troubles are the original impetus for the trip (though later we find out that other couples are struggling in some way).

|

| The group shot |

What none of them know until they get there is that the resort where they are going is one that requires all of them to participate in a bunch of feel-good hocus pocus in order to bring some life back into their relationships.

And on the morning after their arrival, the first thing they are told to do on the beach is strip down to their underwear. I can’t remember the exact thinking about this, but it probably had something to do with needing to bare themselves to each other.

I knew all along that the women were in better shape than the men, but when they took their clothes off, I was simply astonished.

|

| Davis, Akerman, and Bell |

The women—

Kristin Davis,

Malin Akerman,

Kristen Bell, and

Kali Hawk (not pictured here)—are insanely gorgeous specimens, both buff enough to kick some serious cardio butt at the gym and beautiful enough to grace the cover of any magazine.

|

| Bateman, Vaughn, and Favreau |

Though I couldn’t find a picture that included the fourth couple, you can see that they also demonstrate the same double standard in this photo and clip from the movie:

|

| Love and Hawk |

It was at this moment—seeing these two diametrically opposed groups standing across from each other on an idyllic beach in paradise—that I realized there was something really wrong with the expectations we have for female celebrities. Sure, I always knew we held them to unrealistic expectations but never before had I seen such a clear picture of how hypocritical this double standard really is.

Simply put, in our society we are willing to let men look real and still be considered attractive but completely unwilling to make the same allowances for women.

I mean, my God, look at this picture of Kristin Davis:

|

| Kristin Davis in lingerie |

The woman is in her mid-forties (!!!!!), and she still has a body like a twenty-year-old!

That’s just not normal.

And if we don’t allow the women in our movies and on our television shows—in their thirties, forties, and fifties—to look normal or have even an iota of body fat, then how can we ever be happy with our own very real and imperfect bodies? How can we ever see a movie and feel good about ourselves again?

The answer is that we can’t, and until we stop these images from being hurled at us time and again—in our living rooms, magazines, and movie theatres—we stand no chance of accepting ourselves the way we are.

So I say we vote with our dollars and refuse to see movies that feature couples who are so poorly matched on a physical level.

It may take a while for Hollywood notice, but eventually they’ll get the hint.

Molly McCaffrey teaches English and creative writing at Western Kentucky University. Her blog, I Will Not Diet, chronicles her effort to lose weight without unhealthy dieting and encourages readers to reject the notion that curvy women are not attractive. She has been nominated for a 2009 Pushcart Prize, and her work has appeared in numerous magazines and books. She is also co-editor of the newly released Commutability: Stories about the Journey from Here to There. She previously contributed a post about the film Whip It for Bitch Flicks.

She previously contributed a post about the film Whip It for Bitch Flicks.

She previously contributed a post about the film

She previously contributed a post about the film