|

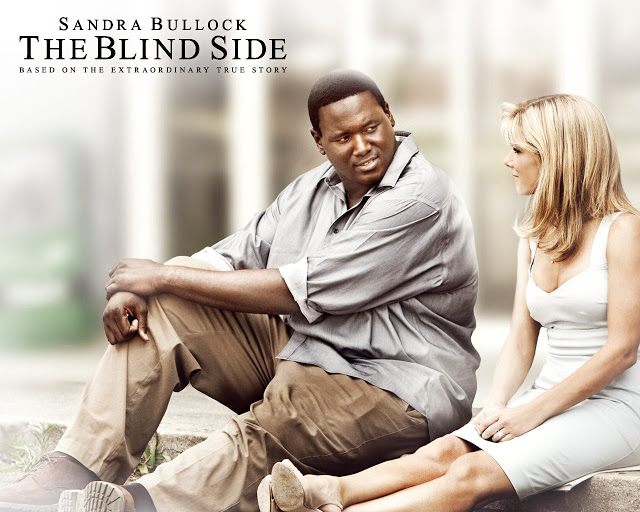

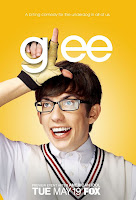

| Movie poster for The Blind Side |

|

| Sandra Bullock schools Michael Oher in The Blind Side |

Let me say up front that I’m aware that I’m supposed to feel sorry for Sandra Bullock this week. She’s purported to be “America’s sweetheart” and all, she has always seemed like a fairly decent person (for an actor), and I think her husband deserves to get his wang run over by one of his customized asshole conveyance vehicles, but I’m finding it difficult to feel too bad. I mean, who marries a guy who named himself after a figure from the Old West, has more tattoos than IQ points, and is known for his penchant for rockabilly strippers? Normally I’d absolve Bullock of all responsibility for what has occurred and spend nine paragraphs illustrating the many reasons Jesse James doesn’t deserve to live, but I’ve just received proof in the form of a movie called The Blind Side that Sandra Bullock is in cahoots with Satan, Ronald Reagan’s cryogenically preserved head, the country music industry, and E! in their plot to take over the world by turning us all into (or helping some of us to remain) smug, racist imbeciles.

The movie chronicles the major events in the life of a black NFL player named Michael Oher from the time he meets the rich white family who adopts him to the time that white family sees him drafted into the NFL, a series of events that apparently proves that racism is either over or OK (I’m not sure which), with a ton of southern football bullshit along the way. Bullock plays Leigh Anne Tuohy, the wife of a dude named Sean Tuohy, played by — no shit — Tim McGraw, who is a fairly minor character in the movie despite the fact that he is said to own, like, 90 Taco Bell franchises. The story is that Oher, played by Quinton Aaron, is admitted into a fancy-pants private Christian school despite his lack of legitimate academic records due to the insistence of the school’s football coach and the altruism of the school’s teachers (as if, dude), where he comes into contact with the Tuohy family, who begin to notice that he is sleeping in the school gym and subsisting on popcorn. Ms. Tuohy then invites him to live in the zillion-dollar Memphis Tuophy family compound, encourages him to become the best defensive linebacker he can be by means of cornball familial love metaphors, and teaches him about the nuclear family and the SEC before beaming proudly as he’s drafted by the Baltimore Ravens.

|

| The Tuohy family prays over mounds of food |

I’m sure that the Tuohy family are lovely people and that they deserve some kind of medal for their good deeds, but if I were a judge, I wouldn’t toss them out of my courtroom should they arrive there bringing a libel suit against whoever wrote, produced, and directed The Blind Side, because it’s handily the dumbest, most racist, most intellectually and politically insulting movie I’ve ever seen, and it makes the Tuohy family — especially their young son S.J. — look like unfathomable assholes. Well, really, it makes all of the white people in the South look like unfathomable assholes. Like these people need any more bad publicity.

Quentin Aaron puts in a pretty awesome performance, if what the director asked him to do was look as pitiful as possible at every moment in order not to scare anyone by being black. Whether that was the goal or not, he certainly did elicit pity from me when Sandra Bullock showed him his new bed and he knitted his brows and, looking at the bed in awe, said, “I’ve never had one of these before.” I mean, the poor bastard had been duped into participating in the creation of a movie that attempts to make bigoted southerners feel good about themselves by telling them that they needn’t worry about poverty or racism because any black person who deserves help will be adopted by a rich family that will provide them with the means to a lucrative NFL contract. Every interaction Aaron and Bullock (or Aaron and anyone else, for that matter) have in the movie is characterized by Aaron’s wretched obsequiousness and the feeling that you’re being bludgeoned over the head with the message that you needn’t fear this black guy. It’s the least dignified role for a black actor since Cuba Gooding, Jr.’s portrayal of James Robert Kennedy in Radio (a movie Davetavius claims ought to have the subtitle “It’s OK to be black in the South as long as you’re retarded.”). The producers, writers, and director of this movie have managed to tell a story about class, race, and the failures of capitalism and “democratic” politics to ameliorate the conditions poor people of color have to deal with by any means other than sports while scrupulously avoiding analyzing any of those issues and while making it possible for the audience to walk out of the theater with their selfish, privileged, entitled worldviews intact, unscathed, and soundly reconfirmed.

|

| Kathy Bates wants to fist bump Michael Oher in The Blind Side |

Then there’s all of the southern bullshit, foremost of which is the football element. The producers of the movie purposely made time for cameos by about fifteen SEC football coaches in order to ensure that everyone south of the Mason-Dixon line would drop their $9 in the pot, and the positive representation of football culture in the film is second in phoniness only to the TV version of Friday Night Lights. Actually, fuck that. It’s worse. Let’s be serious. If this kid had showed no aptitude for football, is there any way in hell he’d have been admitted to a private school without the preparation he’d need to succeed there or any money? In the film, the teachers at the school generously give of their private time to tutor Oher and help prepare him to attend classes with the other students. I’ll bet you $12 that shit did not occur in real life. In fact, I know it didn’t. The Tuohy family may or may not have cared whether the kid could play football, but the school certainly did. It is, after all, a southern school, and high school football is a bigger deal in the South than weed is at Bonnaroo.

But what would have happened to Oher outside of school had he sucked at football and hence been useless to white southerners? What’s the remedy for poverty if you’re a black woman? A dude with no pigskin skills? Where are the nacho magnates to adopt those black people? I mean, that’s the solution for everything, right? For all black people to be adopted by rich, paternalistic white people? I know this may come as a shock to some white people out there, but the NFL cannot accommodate every black dude in America, and hence is an imperfect solution to social inequality. I know we have the NBA too, but I still see a problem. But the Blind Side fan already has an answer for me. You see, there is a scene in the movie which illustrates that only some black people deserve to be adopted by wealthy white women. Bullock, when out looking for Oher, finds herself confronted with a black guy who not only isn’t very good at appearing pitiful in order to make her comfortable, but who has an attitude and threatens to shoot Oher if he sees him. What ensues is quite possibly the most loathsome scene in movie history in which Sandra Bullock gets in the guy’s face, rattles off the specs of the gun she carries in her purse, and announces that she’s a member of the NRA and will shoot his ass if he comes anywhere near her family, “bitch.” Best Actress Oscar.

|

| Sandra Bullock braves the Black Neighborhood |

Well, there it is. Now you see why this movie made 19 kajillion dollars and won an Oscar: it tells a heartwarming tale of white benevolence, assures the red state dweller that his theory that “there’s black people, and then there’s niggers” is right on, and affords him the chance to vicariously remind a black guy who’s boss through the person of America’s sweetheart. Just fucking revolting.

There are several other cringe-inducing elements in the film. The precocious, cutesy antics of the family’s little son, S.J., for example. He’s constantly making dumb-ass smart-ass comments, cloyingly hip-hopping out with Oher to the tune of Young M.C.’s “Bust a Move” (a song that has been overplayed and passe for ten years but has now joined “Ice Ice Baby” at the top of the list of songs from junior high that I never want to hear again), and generally trying to be a much more asshole-ish version of Macaulay Culkin in Home Alone. At what point will screenwriters realize that everyone wants to punch pint-sized snarky movie characters in the throat? And when will I feel safe watching a movie in the knowledge that I won’t have to endure a scene in which a white dork or cartoon character “raises the roof” and affects a buffalo stance while mouthing a sanitized rap song that even John Ashcroft knows the words to?

|

| Sandra Bullock reads a story to her child son and Michael Oher |

And then there’s the scene in which Tim McGraw, upon meeting his adopted son’s tutor (played by Kathy Bates) and finding out she’s a Democrat, says, “Who would’ve thought I’d have a black son before I met a Democrat?” Who would have thought I’d ever hear a “joke” that was less funny and more retch-inducing than Bill Engvall’s material?

What was the intended message of this film? It won an Oscar, so I know it had to have a message, but what could it have been? I’ve got it (a suggestion from Davetavius)! The message is this: don’t buy more than one Taco Bell franchise or you’ll have to adopt a black guy. I’ll accept that that’s the intended message of the film, because if the actual message that came across in the movie was intentional, I may have to hide in the house for the rest of my life.

I just don’t even know what to say about this movie. Watching it may well have been one of the most demoralizing, discouraging experiences of my life, and it removed at least 35% of the hope I’d previously had that this country had any hope of ever being anything but a cultural and social embarrassment. Do yourself a favor. Skip it and watch Welcome to the Dollhouse again.