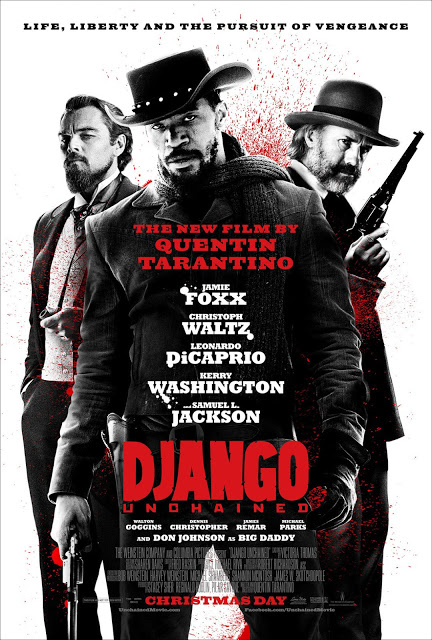

Quentin Tarantino’s

Django Unchained was a movie I never thought I’d see or write about. As much as I adore movies and popular culture, particularly when black characters are front and center, well, the

Crunk Feminist Collective put it best:

“… I am not a fan of Tarantino at all. At all. Generally, I find his work contrived, overly self-conscious, and, frankly, boring. Plus, to me he’s like the worst kind of hipster racist, a grown up version of Justin Timberlake desperately trying to affirm his black card at all times, while thoroughly proving himself to be white as hell…”

I’ll add the caveat that I like Tarantino’s gumption, but that’s where the warm feelings end. Tarantino is the Kanye West of moviemakers: obnoxious as he is talented, arrogant and flippant as he is hard to ignore. America loves men like him. For that reason, he brings up all my contrarian cockles. Between the grotesque violence and excessive use of the N-word in his movies, combined with the fact that I did not appreciate Pulp Fiction or From Dusk ‘Til Dawn, (the only movie I stomped out of mid-way) I saw no reason to spend money to see another Tarantino production.

What led me to the theater, finally, was what always leads me there: deep curiosity and a good friend.

Salamishah Tillet,

writing for CNN’s In America blog, wrote: “There is much to criticize in this film: the excessive use of the N-word,

gratuitous gun violence and its male dominance. Women are objects of apathy or sympathy and are not as nearly as complex or charismatic as any of the male characters. This is very much a movie about how men, white and black, navigate America’s racial maze.”

|

| Dr. King Shultz (Christoph Waltz) and Django (Jamie Foxx) in Django Unchained |

I enjoyed Jamie Foxx at the center of this inverted spaghetti Western. German King Shultz, a hilarious German bounty hunter riding in a carriage with a giant bouncy tooth swaying from its roof, plucks Django from a group of weary slaves and transforms him into a superhero. Viewers are shown flashbacks of Django with Broomhilda, (Kerry Washington) his slave wife who was taken from him. So we get the moments of tenderness without oversexed images. But as Tillet mentions, Washington, like other women, are one-dimensional with no agency.

I feel that I should make the case for a better use of Washington in Django, but it makes sense to me that Tarantino wouldn’t provide any context for black women with agency — he did it with limited success in Jackie Brown as homage to Blaxploitation because the agency of Pam Grier was a seductive plot point. I also would have had to support Tarantino movies for the rest of my life if he had gotten it right. Instead, I felt a sense of relief that a black woman was depicted a damsel in distress, exoticized (she speaks German) but not hypersexualized.

Hildi is worth fighting for and she maintains her dignity. It’s a story I’ve not witnessed before in a Western on the big screen, and rarely anywhere else.

Obstensibly, Django is allowed to exact his revenge on white slave-owners and black men who would keep him from being great. Foxx is the best at this kind of cool glee. He has come a long way from playing the buffoonish Wanda on In Living Color. That his bloodlust is inspired by love and winning back a black woman as a prize allowed this black woman viewer to construct an alternative narrative for his motivations and for the justification of mass murder.

I have also never had the privilege or pleasure of laughing deeply or sincerely during any film set against the backdrop of slavery in the antebellum South. It is humor and wit that carries Tarantino in Django, the unexpected surprise.

In a scene that evokes the KKK with white racist men wearing bags over their heads, there’s a bit where they start arguing about the fact that they can’t see, that one of their wives put a lot of time and effort into the thing and can’t y’all just get over this whole can’t seeing thing? I’ve got a goofy, dark sense of humor, so maybe it was just me, but I could not stop laughing loudly during that scene, in part because it humanizes virulent racists while also mocking their stupidity and vanity in a surprising way.

It also makes you forget what they are, though his accurate portrayal of the harrowing, sickening depth of racist terror reminds the viewer. That felt dangerous and provocative to me. The type of emotions we go to the movies for. Ditto for the score, which blends Blaxploitation with hip hop fantastically, updating the Western with a big of swag.

|

| Stephen (Samuel L. Jackson) and Broomhilda von Schaft (Kerry Washington) in Django Unchained |

Because slavery and violence are rarely spoken about as a kind of spiritual terrorism to say nothing of emotional and psychological antagonism against blacks, I was pleasantly surprised by that accuracy here, explained by Jelani Cobb as violence “deployed as a kind of spiritual redemption” at

The New Yorker:

“And if this dynamic is applicable anywhere in American history, it’s on a slave plantation. Frederick Douglass, in his slave narrative, traced his freedom not to the moment when he escaped to the north but the moment in which he first struck an overseer who attempted to whip him. Quentin Tarantino is the only filmmaker who could pack theatres with multiracial audiences eager to see a black hero murder a dizzying array of white slaveholders and overseers. (And, in all fairness, it’s not likely that a black director would’ve gotten a budget to even attempt such a thing.)”

Like Cobb, and, more famously, Spike Lee, some of my hesitance to support Django had to do with the unfair privilege afforded Tarantino to take creative liberties with not just using racist language with such entitlement (which is how it comes across even if it’s not his intention) but also with the power and assumption of greatness that would never happen for a black director. I find the idea that Tarantino should not be allowed to be great because he calls black folks out of our names to be a symptom of our greater anxieties. The issue to me is not whether or not Tarantino is racist, but that he benefits from the privileges afforded him as a white male to pick and choose his racist tendencies.

There are tons of creative men — white, black, brown — who have this privilege. If they make mediocre films or books, do we stop to analyze why? Well, sometimes. With Tarantino, all the time. In the case of this film, that criticism was a relentless din. I don’t have an answer for why I find that odd and complicated, except that creativity, racism and privilege are embedded in American culture. All creative products are considered superior if they are made by white people. That Tarantino benefits from this is neither his fault, nor is it new. I’m not apologizing for him, I’m simply pointing out why I think the discussion of the flaws in his movie as historical sticking points and the use of the word Nigger miss the point.

|

| Django (Jamie Foxx) and Broomhilda von Schaft (Kerry Washington) in Django Unchained |

But I’m also a sucker for a love story, so because Django is about heroic love, about the kind of victory that necessitates revenge, it thrilled me unexpectedly.

Not just any heroic romantic love, which we never see, really, between black men and women anymore, but also about the love of freedom, the universal thirst for power. At the end of the day, I cared much more that Tarantino was true to that than I do about the Spaghetti Western genre or whether or not the details of slavery were historically accurate. I know enough about history that I would not ever expect Tarantino to offer me an accurate lesson on the institution of slavery.

So, the film is not perfect but as critics agree, it is clever. It is also as close to perfect as we can hope for until someone writes the perfect heroic black love story and revenge fantasy.

———-