On the surface, Sleepaway Camp isn’t much different than your average 1980s slasher movie. The comparisons to Friday the 13th can’t be ignored – Sleepaway’s Camp Arawak, much like Friday’s Camp Crystal Lake, is populated by horny teens looking for some summer lovin’, and is the site of a series of gruesome and mysterious murders that threaten to shut down the camp for the whole summer. But unlike Friday the 13th and other slasher films, the twist in Sleepaway Camp isn’t the identity of the murderer, and the final girl isn’t exactly who you’d expect.

This piece by Carrie Nelson previously appeared at Bitch Flicks on October 24, 2011 and is republished as part of our theme week on Cult Films and B Movies.

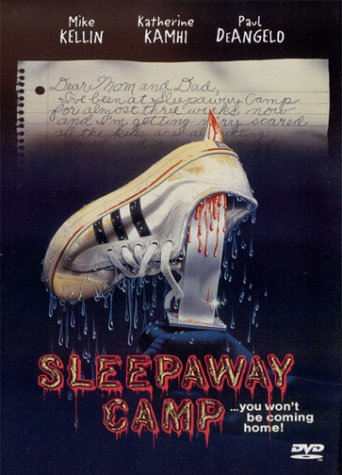

|

| Sleepaway Camp (1983) |

On the surface,

Sleepaway Camp isn’t much different than your average 1980s slasher movie. The comparisons to

Friday the 13th can’t be ignored –

Sleepaway’s Camp Arawak, much like

Friday’s Camp Crystal Lake, is populated by horny teens looking for some summer lovin’, and is the site of a series of gruesome and mysterious murders that threaten to shut down the camp for the whole summer. But unlike

Friday the 13th and other slasher films, the twist in

Sleepaway Camp isn’t the identity of the murderer, and

the final girl isn’t exactly who you’d expect.

(Everything that follows contains significant spoilers. Read at your discretion.)

The protagonist of

Sleepaway Camp is Angela, the lone survivor of a boating accident that killed her father and her brother, Peter. Years after the accident, her aunt Martha, with whom she now lives, sends her to Camp Arawak with her cousin Ricky. Angela is painfully shy and refuses to go near the water, which leads to the other campers tormenting her incessantly. Ricky’s quick to defend her, but the bullying is relentless. One by one, Angela’s tormenters are murdered in increasingly grotesque ways (

the most disturbing involves a curling iron brutally entering a woman’s vagina).

So come the end of the film, when it’s revealed that Angela is the murderer, there’s no particular shock – after all, why

wouldn’t she want to seek revenge on her tormentors? But the fact that Angela is the murderer isn’t the point, because when we find out she’s the murderer we see her naked, and it is revealed that she has a penis. We quickly learn through flashbacks that it was, in fact, Peter who survived the boat accident, and Aunt Martha decided to raise him as a girl.

The ending is profoundly disturbing, not because Peter is a murderer or because he is a cross-dresser (

because his female presentation is against his will, it isn’t accurate to call him transgender), but because he has been abused so deeply by his aunt and his peers that he can’t find a way to cope.

Unlike most slasher movies I’ve seen, I wasn’t horrified by Sleepaway Camp’s body count. Rather, I was horrified by the abuses that catalyze the murders. Peter survived the trauma of watching his father and sister die, only to be emotionally and physically abused by his aunt and forced to live as a woman. At camp, he’s terrified of the water, as it reminds him of the tragic loss of his family, and he’s unable to shower or change his clothes around his female bunkmates, as they might learn his secret. But rather than being understanding and supportive, the other campers harass Peter by forcibly throwing him into the water, verbally taunting him and ruining his chance to be romantically involved with someone who might truly care for him. Not to mention, at the start of camp, he is nearly molested by the lecherous head cook. Peter may be a murderer, but he is hardly villainous – the rest of the characters are the real villains, for allowing the bullying to transpire.

The problem, of course, is that the abuse of Peter isn’t the part that’s supposed to horrify us. The twist ending is set up to shock and disgust the audience, which is deeply transphobic.

Tera at Sweet Perdition describes the problem with ending as follows:

But Angela’s not deceiving everybody because she’s a trans* person. She’s deceiving everybody because she’s a (fictional) trans* person created by cissexual filmmakers. As Drakyn points out, the trans* person who’s “fooling” us on purpose is a myth we cissexuals invented. Why? Because we are so focused on our own narrow experience of gender that we can’t imagine anything outside it. We take it for granted that everyone’s gender matches the sex they were born with. With this assumption in place, the only logical reason to change one’s gender is to lie to somebody.

The shock of

Sleepaway Camp’s ending relies on the

cissexist assumption that one’s biological sex and gender presentation must always match. A person with a mismatched sex and gender presentation is someone to be distrusted and feared. Though the audience has identified with Peter throughout the movie, we are meant to turn on him and fear him at the end, as he’s not only a murderer – he’s a deceiver as well. But, as Tera points out, the only deception is the one in the minds of cisgender viewers who assume that Peter’s sex and gender must align in a specific, proper way. Were this not the point that the filmmakers wanted to make, they would have revealed the twist slightly earlier in the film, allowing time for the viewer to digest the information and realize that Peter is still a human being. (This kind of twist is done effectively in

The Crying Game, specifically because the twist is revealed midway through the film, and the audience watches characters cope and come to terms with the reveal in an honest, sensitive way. Such sensitivity is not displayed in

Sleepaway Camp.)

And yet, despite its cissexism, Sleepaway Camp has some progressive moments. Most notably, the depiction of Angela and Peter’s parents, a gay male couple, is positive. In the opening scene, the parents appear loving and committed, and there’s even a flashback scene depicting the men engaging in romantic sexual relations. Considering how divisive gay parenting is in the 21st century, the fact that a mainstream film made nearly thirty years ago portrays gay parenting positively (if briefly) is certainly worthy of praise.

Sleepaway Camp is incredibly problematic, but beyond the surface-layer clichés and the shock value of the ending, it’s a fascinating and truly horrifying film. Particularly watching the film today,

in an era where bullying is forcing young people to make terrifyingly destructive decisions, the abuses against Peter ring uncomfortably true. Peter encounters cruelty at every turn, emotionally scarring him until he can think of no other way to cope besides murder. Unlike horror movies in which teenagers are murdered as punishment for sexual activity,

Sleepaway Camp murders teenagers for the torment they inflict on others. There’s a certain sweet justice in that sort of conclusion, but at the same time, it makes you wish the situations that bring on the murders hadn’t needed to happen at all.

Carrie Nelson was a Staff Writer for Gender Across Borders, an international feminist community and blog that she co-founded in 2009. She works as a grant writer for an LGBT nonprofit, and she is currently pursuing an MA in Media Studies at The New School.