|

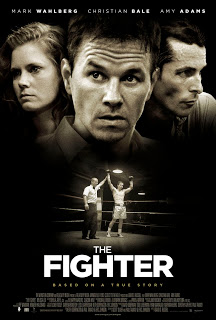

| The Fighter (2010) |

The adage of “Behind every good man is a great woman” is worn out, particularly in the realm of boxing movies. You can reduce the entirety of Rocky to the battered Stallone’s anguished cry of “Adrian!” as he wraps up a brutal fight. We’re meant to believe that what kept him alive was passion, love, a desire to see life through to the closing bell. It’s a hackneyed way of suggesting that though Rocky pounds with his fists, he really leads with his heart. This is the kind of boxing movie that writes itself, and one that doesn’t really need to be seen more than once. Luckily for everyone, David O. Russell’s The Fighter is not that kind of movie. Instead of being a movie about masculine physicality and power, we get a subversive movie about the women that wage real battles outside the ring, the kind of battles aren’t cleanly won.

And they’re right to fear her: with her steely nerve, Alice is as brazen a coach, Mama Rose in the boxing ring, Joey LaMotta in a push-up bra. When Micky goes absent from her immediate purvey, she shows up on his porch with the sisters in tow, posing questions that put him right back in the place of the apologetic son. “What’re you doing, Mickster?” she asks, her eyes all hard with disdain and disappointment. “Who’s gonna look after you?” Alice knows that mother love—and filial obligation—is one of the most powerful weapons she has. “I have done everything, everything I could for you,” she mutters. Her life is bound up in her children, and her coaching mantra is entirely one of maternity. When she catches Dicky sneaking out of a crackhouse, she shakes her head, on the verge of tears, and he has to sing to her like a little boy to pull her back to sanity.

It’s not easy being the son of such a demanding mother, and while Dicky gets to joke his way back into favor, all Micky can do is fight—fight and lose, but fight nonetheless. So it makes sense, given his messed-up family history, that Micky first starts to move out of the nest after falling for Charlene, a local bartender and the first person to call “bullshit” on his family-as-manager situation. (As portrayed by an utterly unglamorous Amy Adams, Charlene is one of the few college-educated characters in the film—due to an athletic scholarship for high-jump.) Charlene’s power in this movie is not as a love interest, but as someone who doesn’t treat Micky like a son or like a brother. She tells him he has to seize control of his career, toss Alice and Dicky off his team, and get serious with a real coach. We think she’s imagining him as a full-grown, self-sufficient man, but she also can’t help but place herself as an equal contender for the managerial job. She gives him a reason to go looking for new management, but she also seats herself decisively by the side of the ring. This is not a woman content to show up after the fight is finished—she is very much an active participant. “You got your confidence and your focus from O’Keefe, and from Sal, and from your father, and from me,” she declares, and there’s not an ounce of hesitation in what she says. It’s thrilling to watch the formerly meek mouse known as Amy Adams get to play someone so fierce.

It’s when the instincts of the protective mother and the defensive girlfriend go up against each other that all hell breaks loose. Alice decides to storm over to Mickey’s house with her daughters in tow, ringing the bell and banging on the door just as Micky and Charlene are doing the nasty. The bell rings and rings, and Charlene, furious at being interrupted, throws on a t-shirt and storms downstairs. Alice pleads with Micky to leave and come back home, but Charlene accuses Alice of allowing her son to get hurt, instead of stepping in and protecting him. In the midst of a boxing movie, what we get is a treatise on how women are the only ones that really know how to fight. Alice calls Charlene a skank, an “MTV Girl” (because clearly all MTV girls are hefting pitches of lager and fending off crude bar patrons), and Charlene lands a solid punch on one of the Eklund sisters. Her fists crunch into the girl’s face, red hair flying wild and legs kicking, and we know that none of these women can be fucked with.

It’s when the instincts of the protective mother and the defensive girlfriend go up against each other that all hell breaks loose. Alice decides to storm over to Mickey’s house with her daughters in tow, ringing the bell and banging on the door just as Micky and Charlene are doing the nasty. The bell rings and rings, and Charlene, furious at being interrupted, throws on a t-shirt and storms downstairs. Alice pleads with Micky to leave and come back home, but Charlene accuses Alice of allowing her son to get hurt, instead of stepping in and protecting him. In the midst of a boxing movie, what we get is a treatise on how women are the only ones that really know how to fight. Alice calls Charlene a skank, an “MTV Girl” (because clearly all MTV girls are hefting pitches of lager and fending off crude bar patrons), and Charlene lands a solid punch on one of the Eklund sisters. Her fists crunch into the girl’s face, red hair flying wild and legs kicking, and we know that none of these women can be fucked with.

Dicky is manic, and Micky is panicked, but it’s the women who are the real pillars of strength. Thus Micky and Dicky are forced to mediate through their female counterparts—Alice, who can’t stand to let her son give up, or Charlene, who forces Dicky into conceding some deeply held delusions. The dual strength of these women are what define the movie, what separates The Fighter from its fellow inspirational tales of athletic triumph, and what catapults it into a movie about athletic effort, and the force of will. And in the movie’s final joyous fight, we still get a triumphant romantic kiss…and it feels anything but hackneyed.

Outstanding review. I’m glad you hit on the dysfunctional family dynamic because I thought it was spot-on, and unfortunately hit a bit too close to home. Charlene represented so many strong women who find themselves held back by a family that does anything it can to keep its children down, intentional or not. This kind of destructive behavior seems almost pathological, and I’m thrilled someone captured it on film.

First, Jessica, I love the phrase “yummy hunk of Irish soda bread” to describe Mark Wahlberg! Awesome.

I hadn’t much interest in seeing the film before reading your review, but am intrigued about the female characters. (A Greek chorus of seven sisters!) Melissa Leo’s character, Alice, does worry me. Not that there aren’t domineering mothers who use filial obligation as a weapon against their children, but the sheer preponderance of them this year bothers me. I suppose I shouldn’t hold that fact against an individual film that happens to have a domineering mother character, but it’s a cultural trend that won’t die, or change, or let up. And that bothers me.

The marketing for the film (that I’ve seen) barely even mentions Amy Adams or Melissa Leo, so we have yet another film that centers around men–and can be summarized with barely a mention of the female characters. A fact of Hollywood films that won’t die, change, or let up, either.

Still, I’m happy to see strong female characters in any movie, and will probably go see this one.

This is a terrific movie. Best of the season in my book. -L

This review makes me want to see this film.

I think Jessica makes an admirable attempt to brush this film against the grain to discover a feminist subtext. Charlene is a dynamic character, and Amy Adams does an amazing job bringing her to life in what is probably her best role yet (and a great sign of roles to come).

I also think the film is technically adept, heart-breaking at points, and mostly entertaining.

Nevertheless, I’m disturbed by at least two aspects of the film. Amber voiced a concern about Alice being a stereotype. There’s no doubt people like Alice exist. Her character is also somewhat complex. She plays favorites with her two sons and suffers from some serious cognitive dissonance about Dicky’s drug addiction. My problem lies with the entire representation of working-class life in Lowell. Micky’s conflict is between his Lowell upbringing and the desire to be a contender, i.e., to escape the vicious cycles of familial guilt, devotion to his brother, the poverty of Lowell, etc. (much like the real Mark Wahlberg, by the way). In other words, the antagonist of the film is working-class Lowell as embodied by Micky’s family. I can’t help but feel like the film looks down upon these characters, especially the seven sisters (although I do love the reading of them as a Greek chorus, which implies that they spout the values of the status quo).

In sum, my first problem with the film is the family. I’m rooting against them and for Micky and Charlene to make it. I want the couple to escape their working-class lives. At the same time, I think the cards are stacked against the working-class characters. Why do they have to be so stereotypical, so easy to dislike? We’re not given enough about Dicky and Alice to put us in their shoes.

My second problem with the film occurs after Dicky gets out of jail when the film magically resolves all the tensions it painstakingly set up, devolving into what many critics labeled as a “sports movie.” Suddenly, everyone’s in Micky’s corner. The aspiring middle class couple can achieve success without betraying the working-class family. Instead of being united against the Russians (as in the Cold War “drama” Rocky IV), we self-identified middle class (but really working-class) Americans can dissolve our differences by hating the cocky British! Who exactly are we fighting in this film? Who should we be fighting in real life?

The ending of the film is all too feel good, the redemptive sequel to the HBO documentary Crack in America. In the first half we are allowed to feel superior to the family, but in the end the family is redeemed because, whether we are willing to admit it or not, most of us are closer to them than we’d like to admit. I think the film should have been more ambivalent about the family throughout. That would have been am unsettling film that would force us to reflect on what we’re fighting for. Instead, I left the theater thinking working-class folk are their own worst enemies and the American Dream is alive and well.

Dr. B–I’m intrigued by your critique of the film as being too quick with stereotypes about the working class. I actually think it’s one of the more nuanced portraits of what drives people into physically dangerous (yet still entertainment-based) careers like boxing. It’s very clear that part of the reason Micky continues to participate in poorly arranged/unequally matched fights is because he knows his family’s economic survival depends on it. “If you don’t fight,” his father says early in the film, “Nobody gets paid,” and it’s his obligation as breadwinner that keeps him in the ring. You can see the same thing with Charlene’s options as a bartender; she went to college on an athletic scholarship, but ended up slinging beers to make rent. People work to survive–one of the things that makes Micky’s compulsion towards boxing so interesting is that he doesn’t seem to love it all that much…(for a film about truly loving boxing, or finding relief in boxing that doesn’t come in real life, check out Karyn Kusama’s Girlfight

But of course, he does like to win. And so does Dicky–but Dicky can’t be in the ring anymore, and the second part of the film makes that pretty clear. You’re right that Dicky’s redemption comes too quickly and prettily. Part of this is the withdrawal he has to go through in prison, but part of what also turns the tables to get us on Micky’s side is how humiliated that HBO documentary makes the family feel. It’s a blast of cold water to everyone, including Alice, who finally sees that her son has a real problem with seeing his own problems as problems. Even if she loves him, she too feels a fair amount of ambivalence about what his future role in Micky’s career should be. And when Dicky has to go convince Charlene to work with him to help Micky, that’s when you see the real humility that comes with getting off drugs and back to a normal, healthy life. Being off crack doesn’t change who Dicky is, but it does give him less to hide behind, and that new honesty is what I ultimately think the film is about. You can fight anyone in the ring, but to fight your family–and fight yourself–for the life you want is the real struggle.

Jess,

A sharp (and necessary riposte). Reflecting more on the film, I think that scene where Dicky convinces Charlene that they are fighting for the same thing is (perhaps) the key scene of the flick. Instead of exploiting each other, the working class should unite in its struggle. Perhaps The Fighter speaks to what’s happening in Wisconsin, Ohio, and .

Thanks for responding.

(I’ve got to get rid of the ridiculous moniker “Dr, B,” a remnant of a course blog, not a sign of unchecked pretension!)