This guest post by Jennifer Krukowski appears as part of our theme week on Dystopias.

George A. Romero’s 1978 zombie classic, Dawn of the Dead, poses many of the same questions as your average zombie flick: what is the difference between living and surviving, and what makes us human? Where Dawn of the Dead stands apart from the rest is its exploration of the childlike bliss of denial in a time of crisis. We don’t know what the world looks like in this particular zombie epidemic because the heroes isolate themselves from it after seeing a mere glimpse of the beginning of the end. The characters spend more time literally watching paint dry than fighting zombies, and yet it is still an entertaining, scary, and thought-provoking experience for the viewer. The end of the world means not having to plan for the future. There’s a banal comfort in that. It is pleasurable to imagine certain responsibilities crumbling away in the wake of a disaster.

Of the four main characters in this film — Roger (Scott H. Reiniger) and Peter (Ken Foree) who are police officers, and Francine (Gaylen Ross) and Stephen (David Emge) who work for a local news station — Francine is the only one who does not indulge in the luxury of denial. She is willing face the scary and uncertain future of the outside world, whereas Peter, Stephen, and Roger prefer to distract themselves from the possibility that there may not be one. Being that Francine is nearly the only survivor, Romero seems to express through this film that, against all odds, hope for a better life — or at the very least, a “real” life — is far more brave than it is naive.

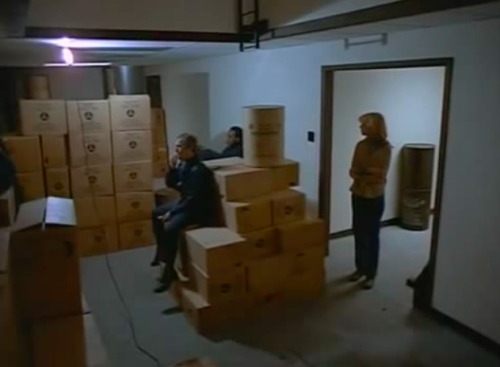

Stephen, Roger, Peter, and Francine flee the city in a stolen helicopter — the most detached mode of transportation available. When they land on the roof of an abandoned shopping mall, the initial plan is to rest briefly, get a few supplies, and move on. As the men sleep, eat, and smoke, Francine paces anxiously, ready to keep moving. Initially, Peter and Roger venture into the mall only to collect a few essential supplies. On their way down, they switch on the power for everything in the mall because “we might need it,” although things like rotating window displays and decorative water fountains are functionally useless beyond creating the illusion of normalcy. As soon as they realize that they have access to a fully stocked department store, the desire for necessity is lost in the wake of a delirious shopping spree. Even Francine’s boyfriend, Stephen, agrees that Peter and Roger are acting like “maniacs,” and yet he grabs a gun that he doesn’t know how to shoot and rushes off to join the fun.

While the men are shopping, Francine is left alone to fend off a zombie with no means of self-defence. As she attempts to escape onto the roof, the others return to save her from the zombie and bring her back inside. She is dismayed to realize that they intend to stay there indefinitely. While the men enthusiastically describe the mall as a “kingdom” and a “goldmine,” Francine describes it as a “prison.” And though it may be smarter to leave, it is certainly more convenient to stay. Squatting in a shopping mall seems like a viable option to everyone but Francine who, feeling trapped and vulnerable, knows that it is too delicate a bubble to settle into. She makes frequent attempts, often subtle and sarcastic, to remind the others that they are simply indulging in a fantasy, most notably when she refuses to accept a wedding ring from Stephen, telling him that “it wouldn’t be real.” If he wants to marry her, he must part with his fantasy life first. He never does.

The dichotomy of real/artificial is exhibited in many ways as the characters go through the motions of daily life, where everything is an imitation of something familiar and resources seem unlimited. Pre-recorded announcements to shoppers are an unsettling reminder of how alone they are. Roger gorges himself on candy and plays an arcade game wherein his character dies, but comes back to life to play another round with no consequence. For a moment, Peter may be contemplating a return to the outside world when he takes money from the bank, but when he and Stephen strike a pose for the security cameras with fists full of cash, he knows that his actions lack consequence, and thus the money, too, lacks value. He will never spend it.

Mannequins, a vaguely threatening presence, are featured almost as prominently as zombies and contribute similarly to the theme. Roger is startled briefly by a mannequin, and the mannequins are also used for target practice. When Francine attempts to comfort herself by indulging in a makeover, she models her hair and makeup after a gaudy mannequin head. It is one of the film’s more disturbing images, reflecting her slow mental break from reality, which she is ultimately able to overcome.

Time seems to stand still for a while in the shopping mall, perfectly preserved and untouched by an outside world that grows increasingly mysterious as radio and television broadcasts become more sporadic. One of the only signifiers of time passing is Francine’s pregnancy. As she nears her due date, her body is as a visual reminder of the inevitability of change, which may subconsciously threaten the others who are less willing to consider the future when, for the moment, everything they need is right at their fingertips. While it would be possible to give birth inside the mall, Francine’s pregnancy forces her more than anyone else to physically experience the passage of time and consider her future, no matter how uncertain it may be. It is very possible that the mall is the safest place for them to be at the time, and while we can only speculate as to why exactly it is so important to Francine that they get away, what really seems to make her nervous is not having an exit strategy. She is the first to demand helicopter lessons from Stephen in case anything happens to him. As Stephen is her lover and presumably the father of her unborn child, it is surely more difficult for her to imagine the possibility of his death than it is for Peter or Roger, but she has the strength to consider the dangerous reality of their situation and prepare for the worst case scenario.

It is not only her future responsibilities as a mother that gives Francine strength. This is a part of her personality. She is often drinking and smoking, so she is not portrayed as a perfect mother-to-be. Not everything she does is for the benefit of her child’s future. While at her job in the television studio, we see that she is highly focused and assertive. When a cameraman walks off the job during a live broadcast, Francine quickly jumps behind the camera and takes over. This example of taking the wheel is mirrored later when she has completed her flying lesson with Stephen, sincerely happy for the first time in the film. It is in her nature to take charge, which is ultimately what saves her life.

Francine may not have a perfect survival strategy. It could be that she is the one who is truly in denial. But in the end, Francine wants to leave the mall, and she does. Roger and Stephen want to stay, and they die inside. When their bubble becomes overrun by looters and zombies, Peter decides that he would rather kill himself than face the uncertain outside world, but at the last moment he changes his mind and joins Francine in the helicopter. They don’t have much fuel and they might not survive, but waiting to die is no way to live, no matter how you pass the time. Although the future probably isn’t optimistic for Francine and Peter, their willingness to face reality is what keeps them alive. At least until they take off.

1 thought on “Killing Time: The Luxury of Denial in ‘Dawn of the Dead’”

Comments are closed.