Too often horror is criticized for being antifeminist. Yes, most often men are the aggressors in these films, and women are shown as the helpless, one dimensional victims. Unfortunately the problem of flat female characters and dominant male leads is not isolated to just the horror genre. In fact, that is a major issue for all of Hollywood. Every day we are bombarded with images of spineless women who need their men to help them fix the car, or assemble furniture, and this might go unnoticed by people because we are so accustomed to these characters. The side effect of the brutality and raw emotion in horror makes it a much more obvious venue for showing our society’s overall angst when it comes to gender issues. Shouldn’t we be equally concerned about the portrayal of all one dimensional characters, regardless of their state of distress? Why is horror the problem here?

When discussing horror as a genre it is helpful to boil it down to basics. Watching horror is a sadistic act. People go to horror films to watch other people be tortured, killed, or humiliated. And we, the audience, get a thrill out of those acts. Whether is it because we like to see those who deserve it be punished, or we just like to feel fear, or we enjoy the thrill of watching pure emotion pour out of the screen, we like it and we want more of it. When it comes to horror films, I think the most feminist act of all is equal opportunity sadism. When the aggressor of this violence (mental or physical) is a woman acting of her own twisted free will, enjoying tormenting her victims, only then do I feel satisfied as a feminist viewer. The character of Baby is why Rob Zombie’s 2003 film House of 1000 Corpses a solidly feminist horror film. More on that later.

The film starts with a set of four college kids as they pull into a gas station and get more than they bargained for. Sounds horribly cliché, right? This is where the genius of Zombie’s film begins to shape up . You see, the film can essentially be broken in to two parts. The first half is essentially a love letter from Zombie to all of the great horror movies of the past. Texas Chainsaw Massacre, The Hills Have Eyes, and even The Munsters gets a reference or two. Zombie spends the first half of the film showing you that he has the knowledge of horror to be able to pull off the second half of the film. From there he takes us down the rabbit hole (literally) to a horrific, indulgent world of his own making.

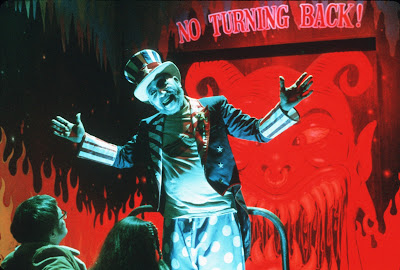

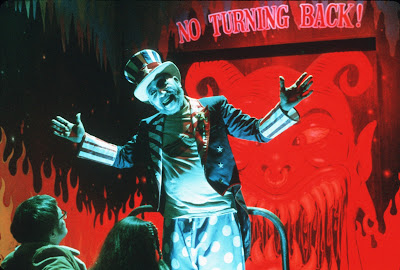

The college kids’ predicament starts after a brief stop at a roadside attraction run by a local character Captain Spaulding (played by genre favorite Sid Haig). The good Captain has just killed two bumbling robbers, but the kids arrive just after that mess was cleaned up. While filling up on gas, kids tour the Captain’s haunted house that rehashes the local legend of a murderer and torturer, Dr Satan.

Stereotypically, the two college guys, Bill and Jerry (The Office’s Rainn Wilson and Chris Hardwick), love the haunted house and the two women, Denise and Mary (Erin Daniels and Jennifer Jostyn), are bored by it. While I do take fault with Zombie for following the general premise that women don’t like that sort of thing, it reads more like an homage to all of the uninterested and nagging girlfriends in past horror films. These four are mostly uninteresting and uncharismatic. But crucially they are equally so. Both the women and the men in this (let’s face it) doomed group are superficially and poorly developed characters. Even Denise’s call home to her ex-cop father doesn’t do much for her. Zombie is saving all of his interesting characterization for the sadistic Firefly family.

Inevitably the college kids pick up a hitchhiker, which is where the plot starts to get interesting. This hitchhiker, Baby Firefly (played by Zombie’s wife Sheri Moon), seems odd and off in her own world. She messes with the radio and giggles at the college kids. Both Denise and Mary instantly despise her and are obviously threatened by her sexuality, and as expected both Bill and Jerry like her. While this little battle starts to play out, and Baby is loudly drumming on the car’s dashboard, the car gets a flat tire. Of course the sexy female hitchhiker is a local and her brother can help fix the car. It is when Baby insists that the whole gang come over to dinner that this story finally becomes interesting.

Baby’s house, and presumably her brother’s tools, isn’t far, so the gang is whisked away to the house for shelter and a quick meal with the Firefly family. If the group of college students had any doubts about whether or not they were in a horror film, all of these doubts were erased at dinner. The whole family shows up to nosh and it reads like a casting call for characters out of horror film history. There is the terrifying and unhinged older brother Otis (Bill Mosley in a career rescuing role), the younger but gargantuan and deformed brother Tiny (Matthew McGrory), the elderly Eddie Munster looking Grandpa (Dennis Fimple’s penultimate role), and the aloof and spineless mother (played by Karen Black). Throw in the required Halloween masks to be worn at the table, and we have a truly motley dinner party.

After dinner the college kids are all but forced to attend the Firefly’s Halloween eve floor show in the barn next the house. The vaudevillian show starts with Grandpa yoking it up on stage. Grandpa’s jokes are sexual, astoundingly offensive, and old fashioned. Both Denise and Mary are obviously disgusted by the whole thing. Jerry loves it. He is eating the provided popcorn and having a great time while he is there. After Grandpa finishes his act Mary and Denise try to talk to Bill and Jerry about leaving. They want to head out on foot to find someone else who can help them. Bill and Jerry quickly dismiss their request because they are in the middle of nowhere and the odds of them getting somewhere safely are nil.

It is a good thing that they stayed. Good for us, the audience who is waiting for the torturing to begin, but not good for our sitting duck college kids.

The next, and final, act in the Firefly show belong to Baby. She starts of stage looking like the type of woman that is created specifically for the male gaze. Her hair is teased up to nearly an afro. She is wearing a skin tight, floor length beaded dress. Her makeup is so extreme it looks like an almost kabuki costume: drawn on lips, exaggerated eye lashes and rosy cheeks. Baby then proceeds to lip sync to “I Want To Be Loved By You” and flit with the male members of the audience.

While Baby does seem to be enjoying herself while performing, it seems more like she is putting on a show for the available young men there. Both Bill and Jerry are enjoying the show very much (to the annoyance for Mary and Denise) but they are not about to act of these impulses. They like to watch Baby dance, but only from as an object and have no real desire to interact with that object. Baby seems to be going through the motions of the show, but ultimately it is an awkward performance. We have seen the real Baby, and this is not her. The real Baby likes to listen to loud rock music and torture cheerleaders. Her empowered version of sexy is wearing ass-less pants and buying cases of alcohol. By performing just for the men, and playing up to the expected male gaze, Zombie is making a comment on the problematic representation of the feminine in film. Here Baby is doing everything right to act the part of a typical Hollywood woman, but it isn’t successful in wooing anyone, and is making more enemies than friends. This antiquated representation of the female is no longer attractive to an audience.

As the performance is going along, and Baby is approaching Bill to sit on his lap while lip syncing, Mary’s jealousy gets the better of her and she tosses Baby from Bill’s lap. Mary shouts at Baby, calling her a slut and a redneck whore. This is totally uncalled for. Yes, Baby was heavily flirting with Mary’s beau, but calling her those names was a bit harsh. Interestingly this is where the film goes rapidly downhill. Baby pulls a straight razor from out of her dress and threatens to cut off Mary’s tits. Here is where Baby really hits her stride and becomes the proactive, violence loving woman that she is meant to be. When Mary insults her misguided attempt at performing the assumed male concept of femininity Baby’s first reaction is to remove one of the most obvious objects of Mary’s femaleness. Insulting another woman with those sexualized names should then make the insulter less of a woman. And by bringing down another woman, she should be punished accordingly.

At this very second the mechanic brother Rufus shows up and declares that the car is fixed and they can leave. We all know that the group can’t leave and that they will be eradicated one by one in very interesting ways. At that moment, though, they all scurry off to the car in hopes of escape.

Throughout the rest of the film Baby and the Firefly bunch torture and terrify each of the college kids, and even Denise’s dad and a sheriff killed after a botched rescue attempt. Each kill is more interesting and inventively than the last, and Zombie has fun showing the audience how sick and creative he can make a modern horror film. Firmly throughout the film Zombie balances the female characters and the male characters equally. There are uninteresting flat college kids of both genders, and both men and women as tormentors. Baby seems to get just as much satisfaction in maiming Jerry as Otis gets in turning Bill into a taxidermy display. It is this even handed approach to the horror of the Fireflys that ultimately makes

House of 1000 Corpses a feminist entry into this classic genre.

Deirdre Crimmins lives in Boston with her husband and two black cats. She wrote her Master’s thesis on George Romero and works too much.

2 thoughts on “Horror Week 2011: House of 1000 Corpses”

Comments are closed.