“We revolt simply because, for many reasons, we can no longer breathe.” – Frantz Fanon

Written by Leigh Kolb.

I saw Concerning Violence six months before Darren Wilson shot Michael Brown. It was six months before white people started wringing their hands to a chorus of “The answer to violence isn’t more violence!” “Look at them destroying property and looting!” “What would Martin Luther King, Jr. say?”

Nine months before the announcement that Darren Wilson was not indicted, white audience members–in Missouri–squirmed in their seat after screening Concerning Violence: “But violence should never be the answer.”

[youtube_sc url=”http://youtu.be/ohoiW9HrXkc”]

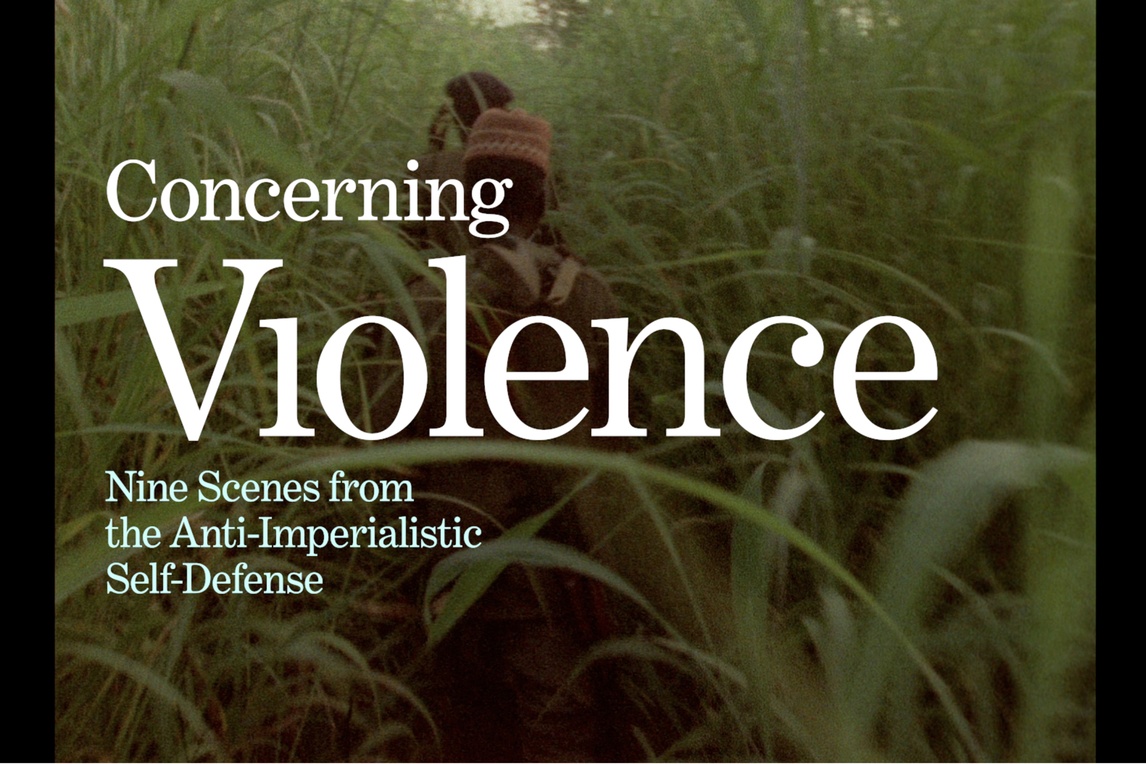

Concerning Violence is a remarkable documentary. Directed by Göran Hugo Olsson (The Black Power Mixtape 1967 – 1975), it weaves together archival footage of African colonization and anti-colonial liberation revolts from the 1960s – 1980s with the words of Frantz Fanon‘s The Wretched of the Earth (1961). The text–read by Lauryn Hill–often appears on screen as she narrates. Technically, the documentary is brilliant. It’s almost as if we cannot feel the director’s presence, because the power of the archival footage and Fanon’s language is woven together so powerfully and without any added commentary (nor does there need to be). Instead, we are assaulted with a perspective we never feel: that of the colonized-as-heroes, by any means necessary.

The stunning, disturbing footage is presented in such a way that we must realize how pertinent it is to America in 2014. The film opens with images of armed men in helicopters shooting and killing a field full of cattle. As Keith Uhlich describes at A.V. Club:

“One animal takes a particularly long time to die, and, with each bullet that doesn’t kill it, convulses in what can only be described, anthropomorphically, as pure fear. The more horrifying implication is that there’s no true word for what the beast is going through, and it’s impossible, by the end of the scene, to not imagine a human being in the same terrible situation.”

From far away, a literal and figurative position hundreds of feet higher than those on the ground, these powerful colonizing forces shoot with savage impunity. The privilege and power are palpable, and this sets the stage for the rest of the film (or, more accurately, for our history). Colonize, control, instill fear, kill, in perpetuity.

I can’t stress this enough: watch this film, and research the various “anti-imperialistic self-defense” histories that you likely never learned about in school.

What is overwhelming to me is the complete cognitive dissonance in white Americans decrying violent revolution. The same utterance of “violence is never the answer!” about protests contrasts with celebrating American history. This isn’t a new dichotomy, of course. In “The Ballot or the Bullet,” Malcolm X said,

“When this country here was first being founded, there were thirteen colonies. The whites were colonized. They were fed up with this taxation without representation. So some of them stood up and said, ‘Liberty or death!’ I went to a white school over here in Mason, Michigan. The white man made the mistake of letting me read his history books. He made the mistake of teaching me that Patrick Henry was a patriot, and George Washington – wasn’t nothing non-violent about ol’ Pat, or George Washington. ‘Liberty or death’ is was what brought about the freedom of whites in this country from the English.”

The word “or” is important here. Just as the American Revolution we celebrate with fireworks (even though there was plenty of looting and a high death toll) was built upon this notion of “liberty or death,” so also are calls to anti-colonial violence in self-defense.

“If you do not liberate us, we must liberate ourselves.” How is this not logical? And if the historical precedence of “liberation” is through violent means, how can we, with a straight face, say that the answer to violence is not more violence? It’s always been white America’s answer.

When we learn about Nat Turner and Malcolm X in school (if we do), it’s in hushed tones. That‘s not the way to get freedom (if you are African American, at least). We know that we receive our history, literature, and film primary from one voice: the white male. Chinua Achebe said, “There is that great proverb — that until the lions have their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.”

Reading Fanon, listening to Malcolm X, watching Concerning Violence–these are just a few ways to hear the lions. When the hunter listens, though, he sees a lion roaring, jaws open wide to bite and kill. The fear sets in. Oppressive control digs its heels back in.

One of the aspects of Concerning Violence‘s archival footage that makes it powerful is that so much of it is in color. We tend to think that the fiercest acts of colonialism and imperialism happened long ago and far away. It’s so important to see a world that looks like our world now, with the weapons and machinery of modernity that colonize now, not 100 years ago. Concerning Violence is historical, but it’s not history. It forces us to be uncomfortable with the world we’re living in, which is the first step to changing it.

Violence is presented as the or. Instead of desiring or justifying violence from the oppressor or the oppressed, we need to consider changing the structure. If people riot and respond to oppression with violence, how can we think that’s unheard of, uncalled for, or without historical precedent? If we do react that way, then we need to drastically change how we teach and understand our own history. If violent revolution is abhorrent, make that clear–even when white men do it.

From the Al Jazeera review of Concerning Violence:

“In her spoken preface to Concerning Violence, renowned Columbia University professor Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak explains that in ‘reading between the lines’ of The Wretched of the Earth, one sees that Fanon does not in fact endorse violence but rather ‘insists that the tragedy is that the very poor is reduced to violence, because there is no other response possible to an absolute absence of response and an absolute exercise of legitimised violence from the colonisers’. Spivak goes on to make a telling comparison regarding the earth’s ‘wretched’: ‘Their lives count as nothing against the death of the colonisers: unacknowledged Hiroshimas against sentimentalised 9/11s.'”

Violence is the or. If the oppressed, the colonized, are not treated as human beings, and are subjected to institutional racism and injustice, thinkers such as Fanon and Malcolm X see the or as revolutionary self-defense. This kind of violence is part of a long history of the oppressed overcoming oppression. That’s why it’s so terrifying to colonial powers and their rhetoric is censored, shut down, and shrouded in fear.

Perhaps that is what is most frightening to those who focus on how abhorrent rioting in the face of injustice and brutality is: they know, deep down, that rioting makes sense. White Americans know–consciously or subconsciously–that Black Americans have reason to respond to violence from the “colonizers.” And that is a terrifying reality.

In Ferguson and the protests that have swept the nation, small pockets of violent and destructive reactions have occurred–almost never by the organized protesters themselves. Even so, one image on the news media of a burned business or vehicle makes many white Americans shut down and refuse to see any legitimacy in wider protests.

White Americans, at the very least, can strive to understand why–in a world bought and won by violence–an oppressed group might see violence as self-defense and justifiable. This is not to encourage violence, to desire violence, or to act violently. This is to pause, take a step back, and just for a moment, listen to the lions. Listen to them roar.

See also:

“Ferguson: In Defense of Rioting,” by Darlena Cunha at TIME; “If Assata is a terrorist, then Timothy Loehman, Daniel Pantaleo, & Sean Williams are terrorists,” by Shaun King at Daily Kos; “When Are Violent Protests Justified?” by Taylor Adams at The New York Times

Review: ‘Concerning Violence’ Visualizes Frantz Fanon’s ‘Wretched of the Earth’, by Zeba Blay at Shadow and Act; ‘Concerning Violence’: Fanon lives on, by Belen Fernandez at Al Jazeera; “Film of the week: Concerning Violence,” by Ashley Clark at BFI; “Living at the Movies: Concerning Violence,” by Jeremy Martin at Good; What’s Happening Now in Ferguson and ‘The Black Power Mixtape 1967-1975,’ by Ren Jender at Bitch Flicks

Leigh Kolb is a composition, literature, and journalism instructor at a community college in rural Missouri.

1 thought on “‘Concerning Violence,’ Concerning Ferguson”

Comments are closed.