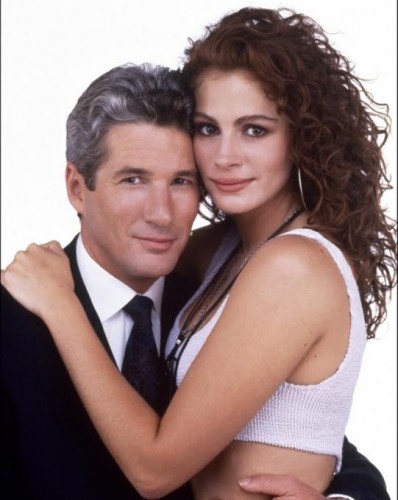

Garry Marshall’s romantic comedy, Pretty Woman, is one of the most popular American movies of all time. A box office success when it was released in 1990, it still rates highly in those Greatest Romantic Comedy lists. Audiences all around the world have embraced Pretty Woman’s buoyant tone, pop soundtrack, Hollywood setting, and fairy-tale love story. The lovers, Edward Lewis and Vivian Ward, make an unlikely couple, of course. He is a wildly successful businessman and she is a hard-up street prostitute. The meet-cute takes place on Hollywood Boulevard. Both lovers have looks and personality, and both are portrayed as engaging and sympathetic. Julia Roberts and Richard Gere give winning movie star performances as the pair. The mass popularity of the love story is, no doubt, due, in great part, to the attractiveness of the stars and the appeal of the characters. Their love is, also, habitually read as perfectly romantic because it seems to transcend all differences.

This is not my Pretty Woman, though. The movie I recognize is a glossy yet insidious Hollywood product that seeks to convince viewers that street prostitutes are eternally radiant and movie star beautiful, and that their corporate clients are all gracious and movie star handsome. I’m not sure that there is a film out there that has sanitized and romanticized prostitution as much as Pretty Woman. The clear intention of the movie-makers is to drug and delude the audience. Music, beauty and fashion serve to seduce the viewer, and mask the fact that they are watching an impoverished street prostitute spend a week with an extremely wealthy man in his hotel room. In response to the question, “Isn’t it just a fairy tale?” we have to remind ourselves that there is no such thing as a meaningless fairy tale. Nor is there such a thing as an apolitical Hollywood film. Pretty Woman may be a fantasy but it’s a deeply sexist, consumerist fantasy.

Julia Roberts’s Vivian does not have the aura of a street prostitute. She is way too sunny and sugary. Although she initially comes across as a trifle feisty and seasoned, the impression does not last. For the most part, the character looks and behaves like an ingénue. Actually, you never even believe the wild child introduction. Vivian’s best friend, Kit de Luca (Laura San Giacomo), is portrayed as earthier and less attractive because Vivian’s essential wholesomeness and beaming beauty must stand out (This is the function of best friends in Hollywood films, of course). Vivian is, in fact, nothing less than a 90s reworking of two of the oldest stereotypes in cinema and literature: the “whore with a heart of gold” and “happy hooker”. Our heroine smiles, sings and laughs throughout the movie with excessive dedication.

It is Vivian’s good-hearted, unaffected ways that enchant Edward, of course. He is smitten by both her spark and beauty. There is, though, a deeply disquieting edge to Edward’s appreciation of Vivian. The makers of Pretty Woman have no problem infantilising their heroine and there is a child-woman aspect to her character. For Edward, it is a vital part of her charm. In one signature scene, we watch him move closer to Vivian to gaze at her laughing gleefully at I Love Lucy rerun on the TV. It is telling that Vivian’s family name is Ward. She is like Edward’s ward. He cares for, nurtures, protects and spoils her. The age difference is both acknowledged and overcome. The kind hotel manager (Hector Elizondo) and Vivian come to an agreement that she is Edward’s “niece” if any guest asks. The age gap is recognized but it is not understood as a major obstacle to true love. Pretty Woman is, therefore, yet another perpetrator of that old Hollywood gender age gap rule. Roberts is nearly 20 years younger than Gere and they basically play their ages. The older man-younger woman intergenerational relationship is normalized and naturalized, and the underlying archaic message is that that a heterosexual relationship can only work if the man is significantly older than the woman. Edward’s not a partner; he’s a patriarch.

Pretty Woman is both sleazy and conservative. The first shot we have of Vivian is actually of her ass and crotch. We see her turn over in bed in her underwear. As she is not with a client but in her own single bed, in the run-down apartment she shares with Kit, the shot is only intended for the audience. It is, perhaps, the most explicit one in the film as the sex and love-making scenes between Edward and Vivian are neither graphic nor intense. We subsequently see her evade the landlord- she can’t afford the rent- by taking the fire escape route. Soon, she will be on Hollywood Boulevard conversing with Kit. The audience does not spend a lot of time with Vivian on her home turf. It is understood as a dangerous, seedy place but it is not depicted with any real grit or insight. The body of a dead woman has been found in an alley way dumpster but this is soon forgotten. Although Vivian is dressed for business in thigh-high boots, she cuts an incongruous, glamorous presence. However, thanks to a lost millionaire in a Lotus Esprit, the good, pretty woman will be magically transported from those streets in fairy-tale, Pygmalion fashion.

Although Vivian is an endearing pretty woman, she does not conform to class-sanctioned feminine styles and behavior. Cue the most famous makeover in modern movie history. To the tune of Roy Orbison’s “Pretty Woman,” Vivian is appropriately dressed and groomed for Edward’s perfumed world. Pretty Woman, unsurprisingly, patronizes its heroine. In the early part of the movie, at least, Vivian is portrayed as a wide-eyed hick from Georgia who spits out chewing gum on the sidewalk and (accidentally) flings escargots around restaurants. Fortunately, Edward is there to guide her. Note that he doesn’t only introduce her to snail-eating but he also takes her to polo matches and concerts. One evening, courtesy of his private jet, he whisks her off to San Francisco for a performance of La Traviata. “The music’s very powerful,” he helpfully notes.

Which brings us to Pretty Woman’s unashamedly antiquated and classist portrayal of Edward. The corporate raider is portrayed as an extremely cultured and intelligent man. He loves the opera, plays the piano, and reads Shakespeare. Pretty Woman does not only have a hilariously Hollywood, and frankly philistine, idea of what constitutes a cultured person but it also suggests that America’s astronomically wealthy are exceptionally intelligent and cultured. “You must be really smart, huh?” Vivian says to Edward, after he explains what he does for a living. This is one of the more mind-boggling messages of the movie.

Along with his tall and slender lover, Edward also embodies Pretty Woman’s lookist ethos. Handsome, self-assured and enormous successful, the businessman is seen as superior to other men. His lawyer (played by Jason Alexander), on the other hand, is a nasty, envious, little creep who attempts to rape Vivian at one point. True to the lookist philosophy of the movie, the scumbug character cannot be conventionally attractive or taller than our hero. In Garry Marshall’s fantasy Hollywood, beautiful equals good. But how good is Edward? The movie’s morality is, in fact, mystifying on many levels. Its hero doesn’t drink and or tolerate drug-taking but he has no problem with hiring out women or buying out companies.

Ideologically, Pretty Woman is a love song to consumerism and capitalism. Yes, Vivian gets to disparage Edward’s superficial, affluent social circle at the polo match: “No wonder why you came looking for me,” she observes sadly–and yes, Edward learns to temper his rapacious corporate ways under her gentle influence- he now wants to build stuff and not just deal in money- but this never destabilizes the system. In fact, the system is, arguably, made more secure through reform. Edward just realizes he shouldn’t be so much of a dick. Pretty Woman depicts a world where everyone is either a card-carrying member of the corporate caste or an obliging subordinate whose primary purpose in life is to serve, drive or blow members of that caste. It is obsessed with things and encourages the audience to share its obsession with things. These include Lotus cars, jets, and jewelry. It also sells the City of Angels, of course. Rodeo Drive is one of the stars of the show. In fact, the whole movie is pretty much an extended Visit California commercial. It does its job well, of course. It’s a sleek product. There are many cars, rooms, gowns and suits to admire. But it’s a sleek Hollywood product jam-packed with dazzling fictions and lies about everything under the sun.

The representation of gender and sexuality in Pretty Woman is equally seedy and reactionary. Prostitutes should be civilized and saved while young women should resign themselves to being sexually objectified. Vivian is, of course, portrayed as a deeply romantic being. When their week together is up, Edward offers to take her off the streets and set her up in an apartment. But Vivian refuses to be his mistress. “I want more…I want the fairy tale,” she says to Edward. We, the audience, are encouraged to see her as an all-American girl driven by the pursuit of happiness. But she is also, at the end of the day, a deeply conventional woman with very traditional aspirations. She gets the fairy tale, of course. But Pretty Woman’s not just a love story; it’s also about becoming the respectable partner of a businessmen. Vivian Ward may be a romantic, sympathetic figure but she is also a woman fated to marry well. They may have changed each other but Vivian is incorporated into Edward’s world. Her illicit sexuality must be contained. We see her appreciate Edward’s beauty in the quiet of the night, but we also see her take pleasure in expensive things that he has bought for her. There is a scene in Pretty Woman where we see Vivian go to back to a store on Rodeo Drive where she was previously snubbed and humiliated by snooty sales staff. Armed with gorgeous purchases and gorgeously attired, she reminds them of their “big mistake.” It’s intended as a crowd-cheering scene of course–we enjoy Vivian’s screw-you moment–but it also expresses an unquestioning acceptance of the Darwinian wealth equals power diktat. When she is finally saved by her prince at the end of the movie, Vivian vows that she will save Edward in return. Will she really be allowed to save him? Will she have a role of her own? Or will she just buy stuff on his credit card?

It would be hilarious if the whole enterprise was actually a send-up of sexual politics and consumerism. No such luck. There is not a whiff of subversion in Pretty Woman. Admire Julia and Richard’s beauty, and sing along to Orbison or Roxette, but never forget that it is one of the most misogynist, patriarchal, classist, consumerist, and lookist movies ever to come out of Hollywood.

The above post about the “The Sex Worker and The Corporate Raider: Dissecting ‘Pretty Woman” is quite informative and have all the significant aspects about the same as well. One must go through the same to attain good knowledge about the same.

The interesting thing about Pretty Woman is how Hollywoodized it is compared to the script ($3000). In the script, Edward picks up Vivian on purpose. It’s a habit of his–saving the 10k his lawyer/pimp friend charges for an escort by picking up a street hooker. Vivian is addicted to crack, and she makes Edward double the amount he agrees to pay her if she must go without crack for the week. It is implied that Vivian will be dead within a few years if she stays on the street, but she still chooses that over working for some pimp. In the end, Vivian falls for Edward and tries to give his money back, but he won’t let her. He leaves her at her apt, abandoning her after giving her a taste of the finer things. It’s wonderfully dark.

The movie is about as slick Hollywood bullshit as could be.