This guest post by Artemis Linhart appears as part of our theme week on Male Feminists and Allies.

Feminism comes naturally to Joss Whedon. Despite his recent rant about the word “feminist” being this day and age’s Big Bad, his shows are precisely that: feminist.

Adelle, Willow, Zoë, Natasha–you name her, Joss Whedon offers a multitude of heroines with a wide range of diverse identities. A topic as extensive as this, regarding a person with as much output as Joss Whedon’s, would serve to fill entire volumes. Accordingly, this article addresses only a few specific aspects regarding the roles of women in Whedon’s oeuvre.

It is Darla who, in the very first scene of Buffy, sets the tone for things to come when she subverts the “Damsel in Distress” routine. What is more, female-fronted bands (as for example the great Cibo Matto themselves) playing the “Bronze” is an entirely normal thing. It is subtleties like these through which Whedon continuously subverts common tropes of fiction and pushes the boundaries of our viewing habits.

What is striking in most of his work is that women are not defined by their womanhood. They are simply characters who happen to be female–much like real life.

This holds true especially for the female villains of his shows. They tend not to suffer from what Anita Sarkeesian of “Feminist Frequency” fame calls “personality female syndrome,” wherein female characters are “reduced to a one-dimensional personality type consisting of nothing more than a collection of shallow stereotypes about women.” In general, their underlying motives are not characterized by psychological or emotional factors concerning “woman issues” or driven by some form of “hysteria,” as is the case in a lot of fiction centering around female villains. While they do tend to use their sexuality as a means of power or manipulation, they are, however, often indistinguishable from the classic, male “bad guy,” were it not for their, often “typically female” exterior.

Bold and Beautiful

Indeed, strong women are altogether normal in Whedon’s work. This suggests that they can be forceful, resolute and–quite simply–badass, without having to look “butch” or display characteristics commonly associated with men. By way of example, Buffy can be described as a stereotypical “Barbie” on the outside, yet that does not make her weak or squeamish. On more than one occasion she is seen fighting demons while wearing a mini skirt or even a prom dress.

Correspondingly, female strength is not something to be fundamentally feared by Whedon’s male characters. On the contrary, it is a desirable quality. It is Firefly’s Wash who puts this so eloquently, as he claims to be “madly in love with a beautiful woman who can kill [him] with her pinkie.”

However, Whedon makes it quite clear that not everyone has to be a hero(ine)–especially not all the time. This is what makes his characters multi-dimensional and complex. There have been many discussions amongst fans concerning Buffy’s “shortcomings” and whether she is truly a strong character. This lively, ongoing discussion just goes to show society’s overly critical attitude towards women in film and TV. Buffy should not have to be denied her strength whenever she shows weakness. After all, human beings (and even superhuman beings like The Slayer) have feelings, are vulnerable and even weak at times.

It is treated quite nonchalantly that Firefly‘s Kaylee is an excellent mechanic who also happens to enjoy wearing a pink, frilly dress. And why wouldn’t she? What Whedon portrays are multi-faceted, realistic characters.

In Buffy‘s musical episode “Once More With Feeling,” Buffy sings, “Don’t give me songs, give me something to sing about!”

And indeed, with Whedon, female characters get not only songs, with prefabricated attributes and story arcs, to work with. They get a chance to flourish into something that is their very own selves. They get real substance, real problems, personalities, flaws–lives.

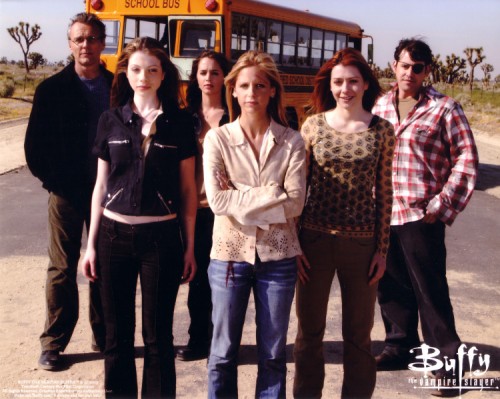

This is mirrored in Buffy‘s series finale, “Chosen,” where it becomes clear that–together with both the “Scoobies” and the “Potentials,” they have created a sheer army of Slayers. Buffy is no longer The Chosen One. It doesn’t take a Slayer to fight evil. Not only does this emphasize that all women can be powerful but, more importantly, it defies the tradition constructed and determined by the Shadow Men. Buffy creates an opportunity for the “Potentials” to unfold and evolve into greater beings–with greater stories.

While all of this should be common practice in today’s fiction, the truth is that it very much isn’t. Therefore, it comes as no surprise that, as a male TV writer, Whedon is praised by feminists despite there undoubtedly being room for improvement.

In spite of all of the female-positive representation in his work, certain aspects remain controversial. There is, for example, Dr. Horrible’s Sing-Along Blog, which has two male protagonists fighting over the affection of their desired female. Penny, seeming innocent and pure, is clearly idealized and functions more like an instrument to the story of Dr. Horrible and Captain Hammer. It wouldn’t be Whedon, however, if he didn’t subvert this cliché framework using nuanced details of clever subtlety.

While the Watcher–considered by some to be the personification of the Male Gaze–in itself is an integral part of the concoction of male authority that is the tradition of the Slayer, and while it is repeatedly undermined by Buffy’s stubborn and autonomous spirit, it remains Whedon who created him. Whedon may place the responsibility on those evil, ancient patriarchs called the Shadow Men, and call it a metaphor for real life patriarchy, yet he allows for a solution only in the very finale of the TV series.

Furthermore, there is a considerate amount of mansplaining in the Whedonverse. Besides Whedon himself, who took the liberty of explaining the word “feminist” to the world, there are such delightful characters, for instance bookwormish Giles or cocky whiz kid Topher–the latter of whom so smugly refers to himself at one point, saying “I don’t want to use the word genius, but I’d be okay if you wanted to.”

Nonetheless, Whedon does offer female counterparts to the likes of them. Bennet Halverson appears as somewhat of a female version of Topher and, unlike Amy Acker’s character, she proves not to be an “Active” imprinted to replace a male scientist.

Jenny Calendar and Willow Rosenberg, on the other hand, function in a very meta way as a modern extension to the intellectual bibliophile Giles. The antiquated order of the man explaining things can’t keep up with the modern world, just as Giles hands over control when it comes to computer-related things.

Innocence

Buffy is certainly no “Final Girl.” While Whedon does play with this trope in Cabin in the Woods, virginal purity is no requirement for the Slayer to survive. What is more, instead of escaping death, Buffy seeks our danger and demons with an aggressive, empowered stance.

Similarly, the sex worker Inara is portrayed in a way that acknowledges her self-determination and poise. Unlike the “metaphorical whores” in Dollhouse, she can take charge of her own work life.

Generally, Whedon’s work resonates with a limited amount of “othering.” This is especially notable in Inaras character, pertaining to her line of work. Whedon incorporates one of the most marginalized professions in an ostensibly non-pejorative manner. While the character of Inara is pro-sex per se, form and content do at times cast her in a “gazed upon” role.

The male fantasy is further exploited, as she is seen in a sex scene with a female client. Though the visual representation of same-sex intercourse merits acclaim, in this case it implies the concept of the girl-on-girl porn fantasy, as Inara is hardly shown this explicitly in her interactions with male clients.

It seems that, not least by making the role of Willow a pioneer of lesbian representation on TV, Whedon has become so idolized that he is now held to much higher standards of feminist sensibility than other TV writers. At the same time, he can get away with a great deal when it comes to questionable representations of gender, sexuality, and relationships. Therefore it is refreshing to see that Whedon’s recent rant has sparked an active discourse among fans. This demonstrates that, while broadly adored, Whedon’s feminism does not remain unchallenged.

Here’s hoping that this will lead to many more positive representations in his cinematic and TV work, including issues inclusive of sexuality as a broad spectrum, as well as non-cis individuals.

See also at Bitch Flicks: Buffy the Vampire Slayer Theme Week Roundup

Artemis Linhart is a freelance writer and film curator with a weakness for escapism.