“Wait!” I said. “There’s another reason I’m out here: I’m here to represent women.”

Dozens of articles have been written about why Occupy Wall Street matters for women. It boils down to one simple fact: Women suffer disproportionately in the current economic climate, which means that a protest for economic equality is a feminist protest—whether it admits it or not. A majority of the nation’s poor and unemployed are women, especially women of color and single mothers.

But the issue is not just what Occupy Wall Street can do for women; it’s what women have already done for Occupy Wall Street.

1970s feminists coined the phrase “the personal is political” when they noticed, by organizing a handful of women and sharing their private experiences, that their everyday struggles were embedded in larger political systems. For instance, women’s unacknowledged and unpaid labor, especially as caregivers for children, directly contributes to our country’s capitalist gains, yet women see no real compensation for it, only a persistent wage gap.

And one of the things I love most about the Occupy Wall Street movement is that it borrows so much of its activism, specifically pertaining to how the protesters interact with one another, from the feminist consciousness-raising model of the 1960s and ’70s. Like consciousness-raising, Occupy Wall Street started with small groups of oppressed people who spoke to one another about their personal struggles, and in doing so, learned they weren’t alone or insane or weak or lazy, the way Those In Charge suggested. That discovery gave them the strength to channel the individual anger and suffering they experienced into a larger collective call to action.

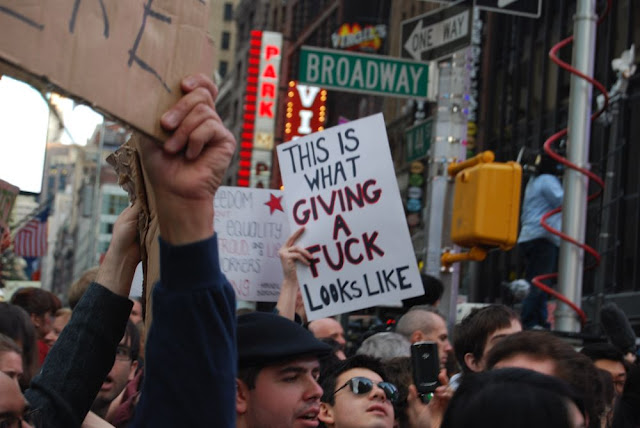

If the personal has ever been political in this country, take a look at the concerns driving the Occupy Wall Street movement: home foreclosures, college loan debts, health problems representing the leading cause of personal bankruptcy, lay-offs and skyrocketing unemployment rates, rapidly diminishing pensions, unaffordable education, unaffordable and inaccessible childcare. On the November 17th day of action, protesters hopped onto train cars and shared their personal stories of how the current economic inequalities have impacted them. One, using the people’s mic, said:

My name is Justin. I was a teacher before my school lost its budget and I was excessed. This is the United States of America, the richest country in the world, and somehow we can’t afford public high school teachers.

And another:

My name is Troy, and I’ve been unemployed for 10 years. Both my sisters lost their homes. I am here fighting for economic justice for everybody on this train … I am united with you in your struggle to pay your bills.

Of course, a large part of consciousness-raising exists on the Internet, and I’ve heard people refer to Occupy Wall Street as the first-ever Internet revolution. Suffice it to say, Occupy Wall Street wouldn’t exist without the fast-as-hell sharing of information over Twitter, personal e-mail exchanges among both participants and skeptics, blogs such as We Are the 99% (a site that showcases photos of people from all over the world sharing personal stories of economic struggle), Facebook (where pages for new feminist groups devoted to Occupy camps crop up daily) and YouTube footage that captures precisely how personal struggle translates into collective political action.

It’s important to note that while early feminists focused much of their energy on gender oppression—and consciousness-raising groups later formed in which women discussed the impact of race—the protesters at Occupy Wall Street have turned the conversation toward class oppression. Of course, race, class, gender and sexuality remain interconnected, but as Felice Yeskel, who cofounded the nonprofit organization Class Action, argues:

Women talked about their experiences growing up in a gendered society as girls and the differential experiences of males and females. And when the issue of race was raised, feminists started to meet in same-race groups, with consciousness-raising for white women about white privilege … But it has never happened in any widespread way about issues of class.

The simple fact? Without the feminist movement and discourse of the ’60s and ’70s, and the consciousness-raising tactics of the civil rights movement before it, Occupy Wall Street wouldn’t exist. We owe it to the women within the movement—and our feminist foremothers—to acknowledge women’s work, and to understand that a movement claiming to fight for the disenfranchised can’t afford to erase the contributions of women. And so I’ll leave you with the words of a woman from a 1969 consciousness-raising group, words that I can see plastered all over Occupy signs everywhere, “Women aren’t in a position to make demands now. We have to build a movement first.”

1 thought on “Happy Birthday, Occupy Wall Street!”

Comments are closed.