This guest post by Athena Bellas appears as part of our theme week on The Female Gaze.

Within contemporary visual culture, girls are frequently positioned as spectacular objects to be looked at. For example, girls are often either positioned as eroticised objects of desire for an adult male gaze, or as pathologized objects of adult concern in order to makes diagnoses about “the problem with girls today.” Both of these gazes police the borders of girlhood, placing girls under the surveillance of a watchful and scrutinising adult eye. In both instances, the girl is positioned as a to-be-looked-at object rather than an active and agentic subject, which means that it is sometimes difficult for our culture to create space to imagine the girl as the holder of the gaze. When we do get representations of girls erotically contemplating the male figure, these representations are often met with derision and dismissal by adult culture. For example, reviews of the Twilight films repeatedly ridiculed Bella Swan’s erotic contemplation of Edward Cullen’s glittering, perfectly coiffed figure as mere fodder for girls’ “wet dreams” (like this is a bad thing), and fangirls shrieking with delight at the sight of their favourite boy band are diagnosed as embarrassingly hysterical and hormonal. This contempt for the girl’s gaze in patriarchal visual culture leads to what Michele Fine calls the “missing discourse of desire” for girls, because there is a consistent shaming, silencing, and erasure of girls’ expressions of desire.

However, even within this complex web of regulatory adult gazes, there are intervals and gaps where challenges and disruptions can take place. There are important spaces within visual culture that provide representations of a girl’s gaze, and I am particularly interested in teen television as one of these spaces. This television genre often centres on representing a teen heroine’s perspective and addresses a teen girl spectator, and the privileging of this frequently dismissed point of view has the potential to disrupt the central position of the adult male gaze. While not all teen TV does this successfully, there are certainly moments within this genre that provide a significant space for the representation of girls actively gazing, exploring, and acting upon their desires. There are, of course, many great examples of girls’ gazes in teen shows like Buffy the Vampire Slayer, My So-Called Life, Veronica Mars, and The 100, among others. In this article, I want to explore the CW network’s paranormal teen series The Vampire Diaries, because it has depicted clear moments in which the gendered terms of the desiring gaze are reversed, turning conventional tropes and iconographies of desire on their head. In this reconfiguration, the girl looks and is (at least temporarily) able to refuse her position as object-to-be-looked-at.

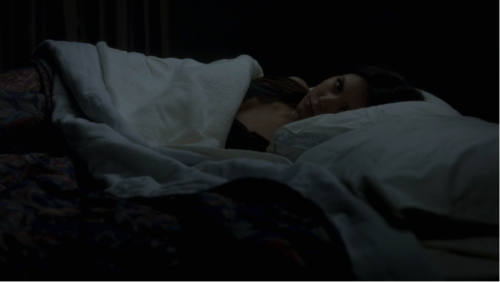

In one of the most iconic scenes from The Vampire Diaries, we can see a powerful, desiring teen girl gaze being represented. Damon and Elena are on a road trip together, and they stop at a motel for the night. At this stage in the narrative, the sexual tension between the two of them is so ridiculously palpable, and everyone is screaming, “Just kiss already!” at their TV screens. Elena feigns sleep, secretly watching a half-dressed Damon sip whiskey as he languorously reclines in a chair.

His bare torso is bathed in the moonlight that streams through the window, creating a beautiful dappled pattern of light and shade across his figure. The camera is aligned with Elena’s gaze, recording the details of Damon’s body in lingering extreme close-ups.

Importantly, Elena is temporarily “invisible” in this scene – her gaze is unmonitored and unreturned as she secretly watches him. In this moment, then, Elena is completely relieved of the conventional position of girl-as-object, and is therefore able to occupy a different position as a desiring subject. By purposefully making herself invisible, Elena momentarily evades and perhaps refuses to be defined by the adult male gaze that governs girlhood. I think that this moment is resistant space where alternatives to the dominant system of desire can be explored. This sequence provides an alternative visual language in which the male figure is made to bear what Laura Mulvey calls “the burden of sexual objectification,” allowing for the representation of the heroine’s active and agentic desire.

In another scene in season four, Damon undresses in front of Elena. In the first shot, we see Elena’s eyes carefully scanning Damon’s figure from head to toe and in the reverse shot, the camera scans and records the contours of his body in intricate detail, encouraging spectators to look at him in the same manner.

Like the scene described above, his body is spot-lit, but this time by shafts of gold sunlight streaming in through the windows, emphasising the openness of his display, and the clarity of Elena’s view of him. Damon unbuttons his trousers and asks Elena, “Are you staying for the whole show or…?” The soundtrack punctuates his playful offer by emphasising the sound of each button popping as he strips off his clothing. Damon recognises his status as Elena’s object of desire, and that he is “on show” for her gaze. As a spectacular object on show, Damon occupies a conventionally feminine position – he is definitely an object of erotic contemplation and spectacle – rather than occupying the traditionally masculine position of action, moving the narrative forward, and control.

By spectacularizing Damon’s figure through the use of extreme close-ups, ultra slow motion, and dramatic lighting, the text invites spectators to look at the male figure through Elena’s desiring perspective. So, the female gaze exists within the narrative world of The Vampire Diaries, and through these representational strategies, spectators are also encouraged to align and identify with it – to occupy and explore this position of active looking alongside Elena. I think that these moments, which reverse the conventional politics of representing the gaze, reconfigure some of the traditional iconography associated with girlhood that ordinarily positions girls as desirable, rather than desiring, and as spectacles, rather than subjects. In this text, we are presented with girls who are able to find moments in which they can evade the adult male gaze, and also claim a desiring subjective position from which to look. This pushes the representational boundaries that often contain girlhood, and I am hopeful that this results in an expansion into new and even more disruptive territories of articulation for the teen girl gaze.

Dr. Athena Bellas has a PhD in Screen and Cultural Studies from the University of Melbourne. Her PhD and current research explore representations of adolescent girlhood in fairy tales and contemporary screen media. She blogs at teenscreenfeminism.wordpress.com and tweets at @AthenaBellas and @TeenScreenFem.