This guest post by Kim Hoffman appears as part of our theme week on The Terror of Little Girls.

CORRECTION UPDATED 2/10/16: An earlier version of this article incorrectly associated the Attachment Center with the Evergreen Psychotherapy Center. We have been informed that The Evergreen Psychotherapy Center has never been, is not currently and will never be associated with The Attachment Center of Evergreen.

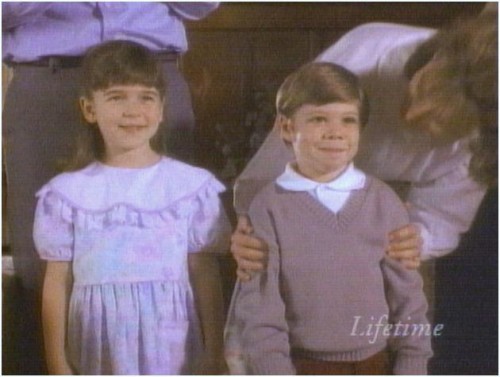

When I was a kid, I was introduced to a movie called Child of Rage, a 1992 CBS TV movie that would be on Lifetime after school. It gave me equal parts dread and fascination—it was about a young girl who wanted to kill her adoptive family, severely traumatized by previous abuse as a baby. What I didn’t know at the time was that the film was based on the real life story of a little girl named Beth Thomas, and that two years earlier in 1990, HBO had released a documentary about the real-life Beth as part of their America Undercover series, called Child of Rage: A Story of Abuse. In the documentary, an oppressed Beth accounts for all the moments I’d seen repeatedly play out in the TV movie, including frank and expressionless accounts of her polluted understanding of right from wrong—like murdering the parents who adopted her and the only brother she’d ever known. I marveled, and still marvel, over the power of this six and a half-year-old child who was never shown displays of love and empathy, until she was prepared to take another person’s life.

Tim and Julie Tennant adopted little Beth and her younger brother Jonathan back in the ‘80s. The couple took the sibling pair into their home, not aware of their past abuse at the hands of their biological father. Her mother, who had abandoned her and Jonathan, died when Beth was one. When Child Services found the children, Beth was screaming in her own soil and Jonathan was found in his crib with a curdled bottle of milk, his head flattened from the way he’d been positioned. Tim and Julie didn’t know about the sexual abuse Beth had been subjected to as early as 19 months old by her father. They didn’t know she was suffering from Reactive Attachment Disorder (RAD), a condition that surfaces from past trauma and neglect into oceans of disturbing, detached, unresponsive, and apathetic behavior. They couldn’t possibly know that a young girl could be filled with so much—that much rage.

In the documentary, a psychiatrist interviews Beth, but he’s one out of a whole team of therapists who guided Beth in her recovery. In 1989, Beth and her adoptive parents went to live with a woman named Connell Watkins, a therapist who practiced a type of “holding” therapy for children who are severely affected by RAD. That same year, a girl by the name of Candace Newmaker was born—but no one would guess that a little over a decade later, the 10-year-old would die in an accidental killing at the hands of Connell and another therapist, Julie Ponder. In that incident, they were conducting a “rebirthing” session in which they wrapped Candace in sheets and pillows to simulate a “womb connection” between Candace and her adoptive mother. Candace had been previously diagnosed with RAD after almost setting her house on fire, and years spent on medicine to keep her rage at bay—often biting or spitting at her therapists. Regardless, this session went terribly wrong. After an hour and ten minutes, the girl’s mother asked if she wanted to be born, and Candace quietly murmured “no”—her last word before dying there in that session. But this event hadn’t taken place yet, not back in 1989 when Beth was dancing the dangerous edge of child murderer and child rehabilitated. Could it be possible?

In the CBS movie, Beth’s character is called “Cat.” The new mom begins to notice Cat’s strange behavior—controlling her brother’s every move, acting jealously about any attention he receives and finding ways to seduce or manipulate adults in order to have the spotlight on her—including a highly inappropriate fondling of her adoptive grandfather. Cat’s coping mechanism for when she’s caught doing something bad includes smashing things and screaming obscenities, eventually retreating into docile panic, holding out her stuffed teddy bear like a wall of armor between herself and the adult—becoming very small and childlike, after displaying such high-strung violence. The most shocking moment in the film is when her new parents catch her bashing her brother’s head into the cement floor in the basement. It’s an eerie scene that sticks with me still, the young boy clutching his dinosaur stuffed animal, and Cat in powder pink sweatpants and tiny little sneakers following him into a corner.

However dark and disturbing, Child of Rage depicts Beth Thomas as a manipulator and seducer to a tee—we begin to see more and more of Cat’s charms and her ability to influence anyone’s move, especially when she knows their move may squash her plan. When the parents find out the truth about Cat’s past abuse as an infant, their worries seem to magnify, especially after so many incidents: Cat kills a nest of baby birds, stabs the family dog with a pin, and slices a classmate across his face with a shard of glass. She lies about her involvement or reasoning and remains sweet—with a tinge of repulsion we can’t help but see slip out from her pursed lips when she draws out, “Yes—Mommy.”

Meanwhile in the Beth Thomas documentary, as she props her head up with her small hand, her eyes widen every once in a while as she explains in detail her desire to kill. Still, it’s obvious that by now in her real-life therapy, she has gone from deceptive to forthcoming, though her remorse is hard to locate from simply observing her. She only trips up once, about the baby birds she killed. The psychiatrist asks her if she thinks the birds could fly or run away from her—she seems confused and half states/half asks, “Yes?” He then asks if she remembers them dying, and she stumbles through an account of her mom telling her that one of them had died, yes. But the psychiatrist goes straight for it—telling Beth, “Your mom told me that you killed the baby birds, Beth.”

Suddenly Beth shows traces of sad emotion that the psychiatrist seems to draw out, coddling her: “That’s OK, that’s OK,” though I don’t know that this is a breakthrough, perhaps just a child whose red-handed admission is still proof she has a long road ahead. This single event was big for Beth; it was her one killing spree. She even admits to hocking a knife from the dishwasher and stashing it in her room. When asked what she wanted to do with the knife, she chirps back at the therapist, “Kill John. And Mommy and Daddy.” She then says, “They can’t see me, but they can feel me,” when she explains why she chooses to sneak about in the shadows while her parents sleep, unaware that their small child could be lurking their hallways yielding a knife.

It’s frightening to watch a child, a real life child, so small on the sofa that her legs barely skim over the side, speaking so candidly about life and death—not to mention her traumatic sexual abuse that no child (or adult, even) can make full sense of and process in a way that any of us should feel is simple. In the film, when the parents take Cat into intensive therapy, the therapist gives them a book called Kids Who Kill by Charles Patrick Ewing, written in 1992, the same year the TV movie aired. If you look up the book, you’ll find it’s connected back to Beth Thomas through the company it keeps in the category of “books on children who kill.”

There’s a lot of speculation over what happened to Beth Thomas after her intensive therapy with Connell Watkins. In the documentary, a woman in a bright track-suit with a cheery disposition talks with hope about Beth’s recovery, while we follow Beth on her chore run around the Attachment Center in Evergreen, Colorado, feeding goats and whatnot (no animals were harmed, seriously). Her name is Nancy Thomas, and she later adopted Beth. It’s rumored that the Tennants kept Jonathan. It’s a little disheartening to think that Beth has had not one, but three mothers. Nancy now owns and operates Families By Design, an organization that provides support for parents and children coping and suffering with RAD. Essentially, it’s become Nancy’s lifework.

Even Beth Thomas herself has participated in many of Nancy’s events, including writing a book that she and her mother wrote together, Dandelion on My Pillow, Butcher Knife Beneath. The book was released in 2010, following Nancy’s previous guide book five years earlier, When Love is Not Enough: A Guide to Parenting with RAD. What Cat displays in the film really illustrates best how easily young girls who are suffering with RAD can use their sexuality in ways that mirror what they’ve seen adults display, though the end result is obvious—that the behavior for how sexuality is displayed in adults is in sometimes lost in translation. How it’s modeled in children who are, as is, sexual beings, but confounded by past trauma in developmental years, can be disturbing and uninhibited. When Cat tells her grandpa that he can be her “sweet, sweet teddy bear,” we have to wonder if baby Cat was influenced by the language she heard from her biological father—the abused taking the abusive language and integrating that into their foundation for bonding, relating, receiving something she wants, gaining total affection and love.

Look anywhere: The reviews on Amazon, web forums, personal websites, reviewers—there is an obvious split among people in support of Nancy Thomas and the practice of Attachment Therapy, and people who, as a result of the Candace Newmark case, find AT and this version of therapy to be abusive and inconclusive—even some adults who underwent said therapy have stepped out over the years to express their concerns over the therapy they were subjected to as children, but, therein lies the toughness with accurately, tangibly calculating whether or not a type of therapy that is aimed at manipulative, violent, disturbed, abused children has: long-term positive effects, or deepens PTSD because of its method.

Something to keep in mind when you watch the film (and I recommend watching the Beth Thomas documentary first, and then delving into the CBS movie last)—the 1992 movie does not mention the word rape, or sex, or vagina, or anything else sex-specific, at all. They hint at the fact that Beth was raped by her biological father through grainy nightmarish flashbacks, and in one instance when Beth shows the sexual abuse through two teddy bears. In the Beth Thomas documentary, she admits to masturbating daily, even sometimes in public, to the point of infection and bleeding and having to be taken to the hospital as a result. She also expresses that she committed similar acts on her brother Jonathan, molesting him at any opportunity she got—which is why Tim and Julie Tennant eventually had to lock Beth in her bedroom for everyone’s safety. All of this, of course, lends itself to the reason why they sought outside help.

Today, Beth works as a nurse, and continues to support her mom Nancy’s organization in Colorado, speaking out about her recovery, and even coming to the defense of Connell Watkins on the witness stand back in 2000. (Watkins served seven years of her 16-year sentence.) Beth professed she wouldn’t be here without Connell. By all accounts, those closest to Beth will attest to her dramatic change and healing. But Attachment Therapy remains the seesaw on the playground when it comes to understanding how to properly heal traumatized children. The Beth Thomas story is a reality—it’s not an afterschool special. For all we know, Beth may very well still have issues—with men, with father figures, with forgiving herself for the acts she committed on her brother, and it may be confounded by the fact that she’s a woman who hadn’t yet grown up and very well had to all at the same time. There was adolescence, teen years, periods, relationships—all of which presents foreign emotion for any girl. Imagine being Beth Thomas, having her childhood, and then facing life head-on. I want to believe in Nancy Thomas, in AT, and in little girls like Beth who “beat the odds” and reclaim life. Again, I ask: Is it possible? Or will she always just be the little child of rage?

[youtube_sc url=”http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g2-Re_Fl_L4″]

Kim Hoffman is a writer for AfterEllen.com and Curve Magazine. She currently keeps things weird in Portland, Oregon. Follow her on Twitter: @the_hoff