This post by Colleen Clemens appears as part of our theme week on Violent Women.

The first college course I ever developed focuses on women and violence. Stemming from my interest in women who enact violence on and off the page, I wanted to ask students to think about our perceptions of women as “naturally” peaceful.

When I tell people that I teach a course on women and violence, the conversation almost always goes like this:

Interested and well-meaning person: “What are you teaching this semester?”

Me: “One of the classes is the course I developed on women and violence in films and literature.”

Interested and well-meaning person: “Wow, there is so much to focus on. Domestic violence, rape, such a hard subject. Are you going to use The Accused?”

Me, trying not to sound like a jerky academic: “Actually the course focuses on women who perpetrate violence. I want to think about what it means when women enact violence as well.”

Long pause. Furrowed brow. Another beat.

Interested and well-meaning person: “Oh. I never really thought about that. Will you talk about Lorena Bobbitt?”

And that is why I developed the course. Because even the most thoughtful among us rarely take the time to consider women beyond the role of victim. When a woman enacts violence, we feel great anxiety because she is dismantling the binary of woman as natural caretaker (see Katha Pollitt’s “Marooned on Gilligan’s Island” for a great discussion of this concept. I start the course with this text). Only men are supposed to be violent. And the texts that portray women as violent actors anticipate this anxiety. When a woman is violent in a film or novel, she often has a reason–often sexual assault–that motivates her violence. The titles of several of these films demonstrate the anxiety we feel about a text displaying women actors of violence. And all of the films tell the story of a woman who was wronged–because that is the only way a woman would ever break out of the rigid mold of care-taking, peaceful earth mother.

_________________________

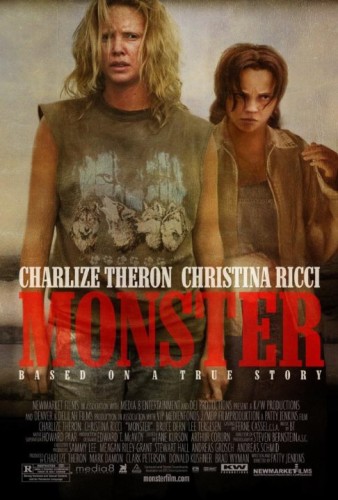

Based on the true story of Aileen Wuornos, this film follows Theron’s character through the development of her serial killing. When raped while working as a prostitute, Aileen kills her attacker. She comes to see that the world she lives in is dangerous and attempts to find a job off of the streets, but those positions won’t take her because they see her as unqualified. She wants to enter the world of “legitimate female work,” i.e., a secretary, only to be told that she doesn’t get to just jump into the world of law.

[youtube_sc url=”https://youtu.be/sraDVyksYMs”]

The film shows us that she has no other choice but to return to the streets, and once there, she kills her johns because she is terrified of being raped again. Until the murders turn. Aileen spares one man only to kill another who offers her help. When is enacting fear of being raped, the audience feels some kind of pity for her. When she takes the life of an “innocent,” she loses the audience’s sympathy and becomes the eponymous “monster.”

Here is where titles start to matter. I ask my students–and you–why isn’t the film titled Aileen? Because that would humanize her. And there is no humanity allowed for a woman that enacts violence. We cannot sit with such an idea that there is something human to her. She MUST be a monster for us to reconcile our ideas of femininity with the character we feel for during the majority of the film. Interestingly, the documentary about her life does use her first name.

If we look at a list of films about serial killers that are based on true stories, most of the titles allude to the name given to the male killer: Jack the Ripper, Doctor Death, Jeffrey Dahmer, Zodiac, the Green River Killer. Monster‘s title does no such thing. She is a monster. No human woman could ever do such a thing. Perhaps this is why so much was made of Theron’s transformation, as if we all needed to be reminded “It is OK. Remember, this is all fake. The most gorgeous woman in the world is under all of that makeup!”

_________________________

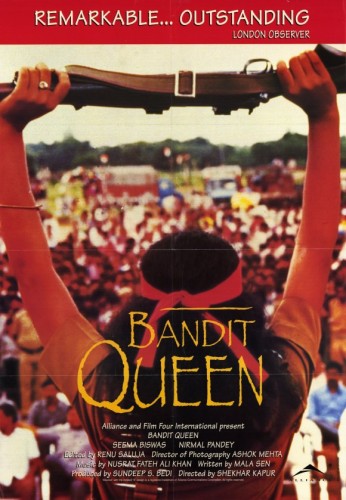

Though I have written about this film before on a piece about the rape revenge genre (for a summary, head on over there for a recap), here I would like to focus on the title of the film.

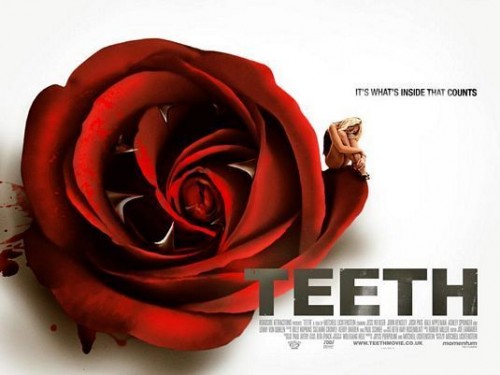

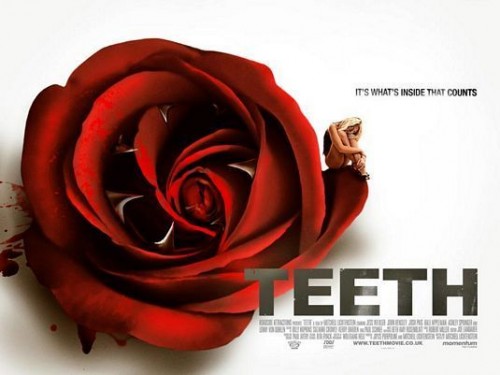

We see a similar trope: girl gets raped; therefore, girl becomes violent. Dawn is literally a lily-white virgin, a “good” girl, until the horrors of patriarchy completely turn her. And her body protects her from further harm.

[youtube_sc url=”https://youtu.be/IA5l86aluqQ”]

Again, the film creates a space for sympathy for Dawn. We can “understand” why she becomes violent through–and in spite of–her biology. Her vagina dentata takes over her thinking self. Then Dawn learns to use it for her own good. And then Dawn becomes a vigilante.

This movie poster is telling. Her vagina makes her squeamish. The power of it is too much to handle for her. Again, why isn’t this film called Dawn? Are her teeth more important than herself? Her toothed vagina is anxiety producing. She is monstrous. Her vagina is all she is, and she must simultaneously protect it and use it protect other women.

_________________________

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo Series

I find everything about the titling of this series fascinating. Stieg Larrson’s orginal title, Men Who Hate Women, has been completely lost on American audiences. Want to blow someone’s mind? Tell her this was the title. So now that we got that fact out of the way, let’s talk about the content and title. Again, we have an assaulted woman who uses violence to enact revenge on those who have wronged her and her family.

Lisbeth is certainly NOT a girl. She is a woman in this film. Infantilizing her and naming the film “the girl” and then pointing out something on her body is similar to naming Dawn’s film Teeth. The body becomes the girl. Because a “true” girl would never, ever do the things these women do–even if their bodies were violated. And why is Lisbeth behind Blomkvist when the trilogy is her story (don’t forget she’s still a “girl” when she kicks the hornet’s nest)? Making Lisbeth Salander a “girl” denies her womanhood because we don’t want to see her as a woman. A “natural woman” would never do what she does in the trilogy.

We shouldn’t forget that all of the characters are being failed by the patriarchal system. Aileen wants to get out of prostituting and is mocked for her attempt. Dawn is told that being a virgin is all that matters, and she is now dirty. Lisbeth is raped by the people in the system who are supposed to be protecting her welfare. Because all three revolt against the system of oppression, we have to “other” them and distance themselves from femininity. It is the only way society can sleep at night.