Written by Mychael Blinde.

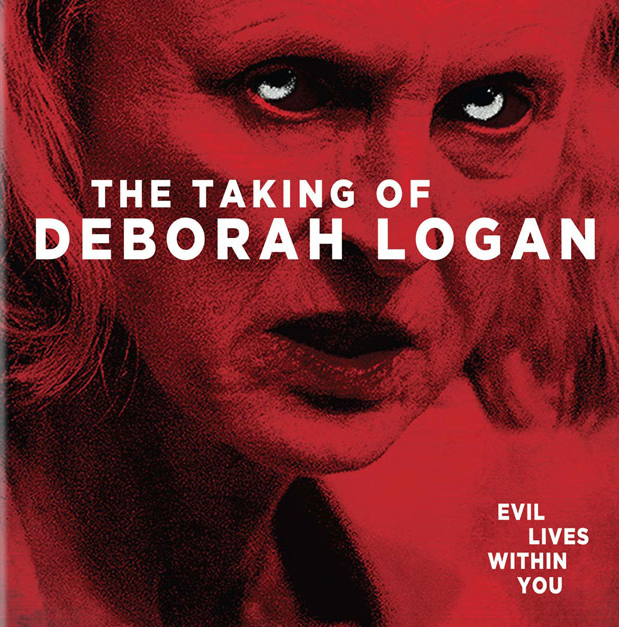

The Taking of Deborah Logan is a story about the horror of evil afflicting a deteriorating mind, but it’s also a tale of the strength of a mother and daughter’s love. Deborah is driven by female characters, and while not a perfect film, it serves up the scares and aces the Bechdel test.

First-time director Adam Robitel presents this found footage movie in the form of a medical documentary gone supernaturally screwy. In this interview, he explains:

What I always wanted to do was start in one space, with a very grounded medical documentary and by the end, turn the movie completely on its head as we careen into full horror movie realm.

Lots of horror fans profess irritation with found footage, but I find it fascinating. Unfortunately, Deborah doesn’t really add anything new to the sub-genre in terms of unique camera work (cf. Paranormal Activity III’s fan-cam or Chronicle’s telekineticams). And yes, the climax falls prey to the same problems as many other found footage films: lots of crashing around in confusion and crappy visibility. (There is, however, one fantastically shocking climactic horror moment like nothing I’ve ever seen before — I will not spoil it for you, but keep your eyes on Deborah because DAMN.)

Still, for the majority of the film Robitel does a solid job of utilizing standard found footage techniques (house cams, whip pans, night vision).

And Deborah manages not to feel too derivative, because the subject of this found footage film is uncommon within the genre: a mother, a daughter, and the sacrifices they make to save each other.

The strength of mother/daughter love is not the most obvious theme of The Taking of Deborah Logan. (The obvious theme is that the deterioration of the human mind is terrifying and akin to demonic possession.) But if we viewers take a step back, we can see how much this film is driven by mother/daughter love and sacrifice: the mother saving her daughter is the reason for the mother’s possession, and the daughter saving her mother is the arc of the entire film.

Deborah begins with PhD student Mia (Michelle Ang) introducing herself and her two-man camera crew to Sarah (Anne Ramsay), the adult daughter of Deborah Logan (Jill Larson). Deborah is in the early stages of Alzheimer’s, and in an effort to help her mother keep her house, Sarah has arranged for Deborah to participate in Mia’s documentary in exchange for money from the project’s grant.

Here’s what we learn about Deborah when Mia introduces her in the documentary:

Mia: After the premature death of her husband…to a pulmonary embolism, Deborah was forced to provide for two-year-old Sarah on her own. She leveraged their house as collateral, and would go on to start a highly successful switchboard answering service for the town of Exuma.

In her preliminary interview with Mia, Deborah describes her role as switchboard operator: “I was the nexus of this town. Doctors, lawyers, town hall, everybody.”

Deborah also details the actions she takes to fight her deteriorating condition, and she expresses her frustration at the futility of her mind’s inevitable decline:

Deborah: I do all my little puzzles. I do crosswords. I’m lifting weights. I am doing everything that I have read will help to stave off the progression of this disease. Stave it off. There’s no cure.

But Deborah’s not just fighting Alzheimer’s; she’s battling a spiritual parasite — and it’s a fucking EVIL one.

Jill Larson is most famous for her role as Opal on All My Children, and according to several different interviews, she had never seen a horror movie before filming Deborah. Nevertheless, as she absolutely nails her role as a savvy single mother afflicted with the frustrating and frightening deterioration of her once sharp mind.

Larson’s portrayal of Deborah’s possession is complex: she conveys a mixture of confusion and fear and desperation and anger and evil, and she appears pitiful, then horrifying, then pitiful again — sometimes in the same scene.

On her approach to the role, Larson says: “My time in soap operas…taught me to invest in situations that sometimes stretch the imagination.”

There exists a cultural trope of the ugly old evil women — a trope which thrives on the notion that older women are scary and unnatural, grotesque, lusting for power and filled with an abject evil.

And yes, as the evil overtakes Deborah, she does become both ugly and powerful.

But Deborah isn’t an evil crone — she’s a good person who is unhealthy of mind through no fault or moral failing of her own. In fact, Deborah is being targeted by the evil spirit as revenge for a brave, heroic deed she committed long ago. Her representation is a departure from the traditional (and trite) evil crone.

The moments we see Deborah naked are not played as gross-out moments (think, for example, the bathroom woman in The Shining). What’s striking about Deborah’s naked body isn’t that she looks gross, it’s that she looks so fragile, so frail.

Her neighbor and lifelong friend, Harris, says of Deborah and her plight: “She’s a fighter. And she’s brave…But how do you fight your way through something you can’t see or know?”

How does Deborah fight her way through Alzheimer’s and spiritual parasitism? With the help of her loyal, brave, determined daughter.

Sarah is there for Deborah every step of the way: from seeking financial aid to seeking an exorcism. At the beginning of the film, Sarah makes sure that the documentary crew is polite to Deborah, and at the end she makes sure that the evil corpse is burned to smithereens. In the climactic sequence, Sarah shouts at Deborah over and over: “Fight him, Mom! Fight him!” From start to finish, Sarah helps Deborah fight her way through.

Sarah is actually supposed to be the subject of interest and the true focus of Mia’s project:

Mia: The story of Alzheimer’s is never about one person. My PhD thesis film posits that this insidious disease not only destroys the patient, but has a physiological influence on the primary caregiver.

Sarah makes huge sacrifices for her mother. She is the character who figures it all out; she has the brains to find the dead body, the guts to grab it, and the presence of mind to destroy it. Sarah is the hero.

She’s also gay.

Reader, I do not identify as gay, and if you do and you think my thoughts are off base here, or if you have any thoughts to add, please share them with me. Here are mine:

I think it’s a great thing to see a gay lady occupy the role of the horror film hero, and I think Sarah is a great gay lady hero. She is a likable, brave, smart, and loyal. And because Sarah’s sexuality is not particularly relevant to her mother’s possession, we get a representation of a gay character who just happens to be gay — it’s not a plot point, it’s just the way things are. Of course I am not suggesting that this is what all representations of gay characters should look like — I’m just saying that I think it’s nice to see a character who happens to be gay, like a zillion other characters in a zillion other movie happen to be straight. I think that this is a positive, beneficial representation.

Speaking of positive, beneficial representations, let me add that I appreciate the number of women with key roles in this film. Deborah, Sarah, Mia, the doctor, and the sheriff — women drive this film. Women and Alzheimer’s.

Robitel explains why Alzheimer’s lends itself so well to the horror genre: “Alzheimer’s deals with two of our most primal fears: Losing our minds and our own inevitable mortality.”

Reader, here’s another disclosure: I have no personal experience with Alzheimer’s. I have misgivings about enjoying this film, because I know that inherent within its plot is the potential for exploitation. But is the representation of Deborah Logan an exploitation or an exploration of the disease? Are we viewers exploiting people who are struggling with Alzheimer’s? Or does Deborah shine light on the challenges faced by people with Alzheimer’s, and celebrate the strength and sacrifice of both patient and caretaker?

The film seems aware that exploitation is a potential issue and addresses the concern head-on: in the opening scenes, when Mia and the crew are first speaking with Deborah about the project, Deborah explicitly states, “I’m not interested in being exploited. I’m not the butt of anyone’s joke.” Deborah never makes its protagonist or her Alzheimer’s the butt of any joke. The film asks us to admire her strength, to pity her deterioration, to fear her possession, and to root for her salvation — it never asks us to laugh at her.

Robitel on his approach to Deborah and the disease:

We wanted to treat Deborah with dignity because it makes her a nice, round character and it also makes her decline all the more upsetting. That said, at the end of the film we realize that this is something else entirely. We knew if we stayed too “real”, it would have felt exploitative. We wanted the audience to have the discussions and start a conversation, but were very mindful that it needed to go more into the expressionistic horror to provide the ‘escape valve’ of entertainment.

The realization that Deborah’s sickness “is something else entirely” starts about a half an hour into the film. Her doctor examines a weird, scaley rash on Deborah’s back and then informs the documentary crew: “This condition is not typically associated with Alzheimer’s. Although when the immune system is compromised sometimes co-infections can occur.”

The doctor’s line is example of one of the many parallels Deborah draws between physiological/psychological deterioration and demonic possession. Robitel states: “Alzheimer’s is a pretty organic metaphor for possession and I think the best horror films take the horrors of real life and then turn them on their head.”

Here’s Larson on what makes the film so scary:

I think a lot of the scary elements come from bringing the audience into a situation that many of us can recognize, because many of us have been touched by Alzheimer’s in one way or another and recognize how frightening it is.

And here she shares her personal experiences with the disease:

I had lost my mother three years before we shot the film. She had Alzheimer’s so I have a lot of feelings about the disease including genuine terror of ending up like that myself.

My instinct is to embrace possession as metaphor for mental deterioration (and vice versa), and to respect this film’s musings on the horror of degenerative diseases and the capacity for strength in a mother and a daughter’s love.

What do you think?

________________________________________________________________________________

Mychael Blinde writes about representations of gender in horror at Vagina Dentwata.

1 thought on “‘The Taking of Deborah Logan’: Alzheimer’s, Possession, and Mother/Daughter Love”

Comments are closed.