Written by Rachael Johnson as part of our theme week on The Great Actresses.

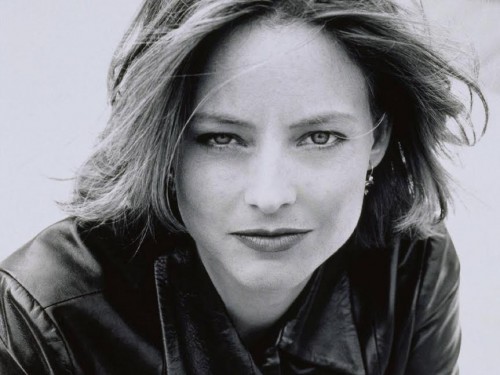

Jodie Foster occupies a unique place in modern American cinema. She is an exceptional, award-winning actress, charismatic movie star, pop culture heroine and feminist icon. Fêted for her memorable, ground-breaking roles in films like The Silence of the Lambs (1991) and The Accused (1988), Foster has dramaticized American femininity for decades. She was, of course, a gifted child actress–often playing precocious, self-possessed, street-smart girls–before making a highly successful transition to adult performing, and winning two Best Actress Academy Awards in her 20s. Very few actresses have, in fact, enjoyed Foster‘s international, inter-generational and cross-gender esteem and popularity. Possessing mass and cult appeal, the bilingual, Yale-educated Foster has, moreover, been popular with both mainstream and indie audiences. Although the adult Foster fulfills conventional ideals of female beauty, she has never been a traditional Hollywood sex symbol. She has been both a figure of identification and desire. In many of her roles, she personifies female independence, heroism and resistance. As an actress, she brings a naturalism, intensity, and integrity to her performances. She engages audiences both intellectually and emotionally.

There have been bad and mediocre movies, of course, like Stealing Home (1988), but Foster has starred in a string of good and great films. The Silence of The Lambs (1991) and Taxi Driver (1976) are, simply, masterpieces. Foster has worked with the likes of Martin Scorsese, Spike Lee, David Fincher, Jonathan Demme, and Neil Jordan. But although she has chosen American auteurs, she has not, interestingly enough, shown great interest in avant-garde and experimental cinema. The California native is, it seems, a populist. A child of the movies. In her autobiography, My Life So Far, Jane Fonda explains that she adheres to David Hare’s belief that “the best place to be a radical is at the center.” Foster has, of course, never been as politically engaged as Fonda in her public life, but perhaps she feels that cultural representations of femininity can be transformed from the center. Although there have been historical films, such as Sommersby (1993) and Anna and the King (1999), most of her films are set in modern America. Foster has always been of her time. Dramas, crime films, psychological and action thrillers appear to dominate her filmography (at least as an adult) although she has performed effectively in more comic roles. She is amusing and engaging in both Maverick (1994) and Nim’s Island (2008).

Foster has a distinctive screen persona. In films such as The Silence of the Lambs (1991) and Contact (1997), she has memorably personified female heroism and self-determination. Her characters destabilise old-fashioned ideals of girlhood and womanhood, and contest reactionary cultural attitudes. Audiences are accustomed to seeing Foster’s characters occupy professions traditionally dominated by men. She plays a scientist in Contact (1997), an aircraft engineer in Flightplan (2005), and a power broker in Inside Man (2006).

Foster, of course, plays an FBI agent in The Silence of the Lambs, Jonathan Demme’s masterful adaptation of Thomas Harris’s novel about a young woman’s hunt for a serial killer. Clarice Starling is a pioneering character in mainstream American cinema. Female protagonists have been traditionally rare in the thriller and horror genres and Clarice challenges masculinist power and privilege as well as traditional expectations of gender. Uncommon for a female character in the thriller and horror genres, she is an intelligent, resourceful, independent woman graced with self-will and self-control. Clarice is unusual in other ways. A woman of physical and moral courage, she makes goodness interesting. This is remarkably rare in cinema. Silence also deals with myths and sexuality in Gothic fashion and Clarice encounters two powerful charismatic father-figures on her quest. Clarice’s boss acts as a kind of paternal figure as well as mentor, and the man who helps her catch the killer, Buffalo Bill, is a seductive, patrician psychiatrist and cannibal serial-killer called Hannibal Lecter. Foster’s Clarice has an appealing sincerity and humanity, and her more naturalistic interpretation of the character contrasts beautifully with Anthony Hopkins’s theatrical incarnation of Lecter. We know, as Lecter knows, that Clarice will never give in and never sell out. The strongest and most moral character in the film, she treats everyone she meets with compassion and respect. Most of all, she represents the female victims of Buffalo Bill while embodying the aspirations of her fellow working-class women. For the orphaned Clarice’s origins are modest and her history is also marked by tragedy.

Foster‘s choices and performances reveal an awareness of outcasts and outsiders as well as an empathy with victims. She has played privileged women in films like Panic Room (2003), The Beaver (2011), Inside Man (2006) and Carnage (2011) but she has, I feel, secured her greatest performances playing women with disadvantaged backgrounds. Although they are often victims of patriarchy, male sexual exploitation and violence, they are not devoid of hope and strength. In Taxi Driver (1976), Foster plays a child prostitute and gives her character, Iris, both spirit and vulnerability. It is a performance that both impresses and disturbs. The actress was in her early teens at the time. The young woman of The Accused (1988), Sarah Tobias, is even less advantaged than Clarice and enjoys none of her esteem and authority. In The Accused, Foster personalizes working-class female pain. Based on a true story, Jonathan Kaplan’s drama is about a waitress who is gang-raped in a bar. The harrowing film chronicles Sarah’s fight for justice. It is one of Foster’s most socially-aware roles and fully-realised performances. Although a victim, Sarah is committed to bringing the men who witnessed and were complicit in the rape to trial. The film itself formally resembles a television drama but the characterization of the female protagonist is strong. Sarah is simultaneously vulnerable, child-like, spirited, all-too-human, tough and moral. Foster interprets her with understanding and humanity. It is an extraordinarily sensitive and multi-layered performance.

In the first decade of the Millenium, Foster’s iconic reputation as a figure of female independence and defiance was further consolidated. Panic Room (2002), Flightplan (2006) and The Brave One (2008) are all about women fighting back. In Panic Room, Foster’s privileged yet vulnerable character suffers a home invasion. Intruders, in fact, break into the Manhattan brownstone of the newly-divorced Meg Altman (her husband has left her for another woman) and her child the night they move in. The mother and daughter retreat to a panic room. Directed by David Fincher, Panic Room is a better, more stylish film than Flightplan and The Brave One. It is thrilling, and satisfying, watching Foster’s character outwit and defend herself, and her child, against the men. For the majority of the film, she is alone with them and when her ex-husband finally arrives to check in after being contacted, he is injured and disempowered by the intruders. It is, therefore, Altman who plays the dominant parental and conventionally heroic role. Flightplan is about a widowed aircraft engineer whose child disappears on a flight to the United States. The film replays Hollywood clichés- Foster is entirely alone and no one believes that she even has a child- and the plot, unfortunately, disintegrates. The role is, also, a somewhat reheated, more narcissistic, version of the part she plays in Panic Room. The Brave One is the tale of a talk show host who turns into a vigilante after her fiancé is killed in a street attack. Neil Jordan’s New York set film is politically suspect and lacks credibility, to say the least, and Foster’s character’s fate is highly unlikely. The actor is, of course, watchable in both Flightplan and The Brave One. She also exhibits a credible screen athleticism in the three films. But it is Foster’s turn as a fixer in Spike Lee’s Inside Man that is, arguably, her most interesting role of the last decade. Sleek, elegantly-attired, bare-legged, playful and ruthless, Madeleine White is, perhaps, the actor’s most seductive performance.

Foster is a beautiful woman but the cinematic display of her sexuality has never been conspicuous- not in the traditional Hollywood sense, at least. Regarding her screen and star personae, Foster is feminine, boyish, androgynous, athletic, cerebral, articulate, rational, charismatic and engaging. The fact that Foster is a gay woman who has only recently disclosed her recently–I shall come to this later–adds an interesting complexity and mystique to the gender representation and sexuality of her roles.

Foster has never been an average female movie star. She has, for the most part, successfully evaded the standard, misogynist discourse surrounding other Hollywood actresses. She has not been a regular target of tabloid-concocted crap about failed relationships, lovelessness and inner emptiness. Equally, we don’t associate the actor with Oprahesque confessional narratives. Nor does she seem to suffer what many stars have suffered from over the ages: culturally-constructed psychological and physical female self-hatred. Foster has never played a highly visible public role and has always fiercely guarded her privacy. Personally, I am not greatly interested in the private lives of Hollywood stars and have always admired her refusal to indulge in daily self-exhibitionism. Her devotion to privacy only enhances her mystique and coolness, of course. It also means that we do not know that much about her.

Although Foster is, it seems, liberal, we know very little about her ideological beliefs. She is not politically engaged like Susan Sarandon, George Clooney, Sean Penn, and Maggie Gyllenhaal. Regarding gender representation and politics, her feminist reputation has issued, for the most part, from her roles. She has, of course, never been a gay role model in a public, politically engaged sense. In fact, this has been deeply problematic for some. Indeed, Foster has been criticized for not coming out earlier in her career. America was, of course, a less liberal place in the 80s and 90s, in terms of gay visibility and rights, and perhaps she thought such a move would jeopardize her career. Did her reluctance to come out publicly reflect pure self-interest and moral cowardice? Was it simply judicious or fundamentally a reflection of a long-cherished commitment to keep her private life private? This fierce regard for privacy is understandable in the light of John Hinckley’s attempted assassination of President Reagan in 1981. A mentally unbalanced man, Hinckley shot Reagan to make an impression on the young actress. Foster has become more open over the last decade, and she does not seem to mind relating fun things about her family life (she has two sons) in talk shows. She came out publicly at the Golden Globes in 2013 (she won the Cecil B. DeMille award last year) but even her coming out was executed in a somewhat idiosyncratic fashion. The speech is an interesting one. A little nutty and cryptic, it is also a quite powerful plea for privacy and understanding. Relating how she came out in private when she was younger to people close to her, she referred movingly to her very public childhood. Foster also seemed to quit acting in the speech but I am somewhat skeptical about entertainers’ public pronouncements about retiring.

Her public image, of late, has, in fact, been somewhat tarnished. Her professional relationship with Roman Polanski–he directed Foster in Carnage (2011) (as well as her friendship with Mel Gibson)–has considerably undermined her status as a feminist icon. Her decision to work with Polanski was all the more disappointing because she is a well-regarded, beloved feminist icon, of course. Discussions about the morality of the artist are thorny, and I am not generally a fan of boycotts of artists and censorship, for art is ultimately about knowledge, but I found the actor’s decision to work with Roman Polanski not only deeply troubling but also perplexing. Sarah Tobias is, after all, the most iconic rape victim in mainstream US cinema and The Accused, as Foster knows, was not just a movie. It sought to educate and change attitudes about rape. Sarah represents victims of sexual violence and she embodies all women. In this way, Foster’s choice constitutes a betrayal. I don’t think any entertainment journalist asked her any searching, intelligent questions regarding her decision. What does it all mean? What were her motivations? We can only hope that she will make wiser, saner choices in the future and console ourselves with the thought that her iconic feminist roles still belong to us.

Foster’s odyssey has been unique. Her immense cultural significance in modern Hollywood history cannot be overstated. Some of the most unforgettable representative roles of popular feminism have been played by Foster and her great, prized performances constitute invaluable contributions to cinema. A pioneer as a child and as a woman, she will always be a part of America’s social and cultural history. Foster has represented girls and women in America and around the world- for over forty years. She will always be Clarice, and she will always be ours.

1 thought on “Reflections on a Feminist Icon”

Comments are closed.