Written by Leigh Kolb as part of our theme week on Cult Films and B Movies.

The designation of “exploitation” is, one would imagine, a negative, damning designation (if that one was an anti-sexist, anti-racist viewer, that is).

When I long ago came across the terms “blaxploitation” and “sexploitation,” something in me instinctively said, “These things are not for you.”

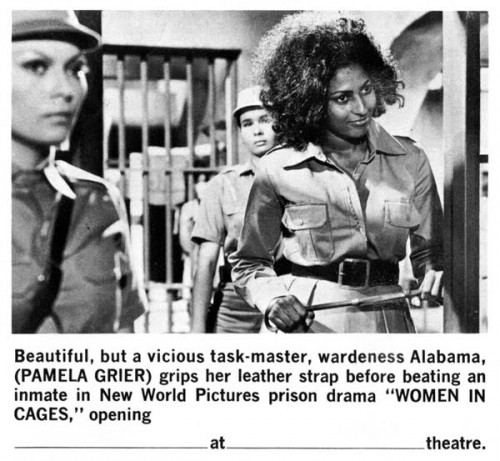

The presence of Pam Grier in so many of these 1970s films, however, made me wade into the genre. I’m so glad I did.

Last year I wrote about some of Grier’s early “blaxploitation” films (Sheba, Baby; Coffy; and Foxy Brown) in “The Unfinished Legacy of Pam Grier.” I was amazed at how not exploitative those films were. They weren’t perfect, but they featured fully realized, empowered black characters and women characters. Grier’s role as a powerful female protagonist in those films shocked me, and made me realize what a dearth of empowered women and black character we have in film today. Could the criticism of “exploitation” by the establishment have anything to do with criticizing flipped narratives, where the white man is the villain? I wonder.

Roger Corman–a director and producer who oversaw a huge number of low-budget films–served as a producer for three iconic “Women in Cages” films, which borrowed from the women-in-prison genre. These three films–all of which feature Grier–are exploitative in regard to female nudity, but their inclusion of relatively complex, powerful women characters is noteworthy. There are evil women, rapist women, drug addicts, innocents, victims, and everything in between.

Orange is the New Black, the original Netflix series based on the memoir of the same name, seems groundbreaking in its representation of all different women battling against one another and against common enemies. The diversity of the women has garnered a great deal of attention, and we feel satisfied seeing women who aren’t just good or just bad reflected back at us. (There has also been some criticism of the lesbian relationships, which have been accused of catering to the male gaze.)

Rewind the clock 40 years, and you get a series of “Women in Cages” flicks with Corman at the helm. And while these three films have male directors, Corman often gave women the opportunity to work behind the scenes and direct films, and he was a proponent of having political messages in his films–even if they seem to be obscured by bare breasts.

All of these films have a few commonalities, besides the prison setting. Shower scenes, rape scenes (female on female, female on male, or forced male on female), evil wardens, and plotting prisoners are woven throughout. The elements of a women-in-prison film are fairly predictable, and oftentimes jarring and offensive.

However, underneath the low-budget production and the sometimes-spotty acting, there are subversive messages about patriarchy and women’s power (or the lack thereof). The evil characters are abusive men and women who perpetuate violence (sexual and physical) against prisoners, who are often in prison for self-defense and addiction. There’s a lot of lip gloss in these prisons, and a questionable lack of undergarments, but the underlying themes are clear and poignant.

I found myself wondering about the designation of sexploitation. Female nudity in itself isn’t exploitative. Women fighting and women being abused are things that happen in prison. Are representations of women in these situations inherently exploitative, or are we conditioned to see women’s bodies and women’s actions and think: object? Certainly frame after frame of powerful, complex, awful and good, sympathetic and loathsome women has some kind of effect on the viewer. Since we are conditioned to only really consider the straight white male gaze as the norm, we see these movies as highly sexualized and exploitative.

I couldn’t help but think, though, that if male viewers find these scenes incredibly sexy and tantalizing–there’s something troubling going on. That the female body–being picked for nits, showered, tortured, working in fields–is always a sexual object is more troubling than the genre itself.

These women have agency, and if they don’t, we’re supposed to be critical of that.

Last year’s documentary Grey Area: Feminism Behind Bars explored the transformative power of feminism behind prison walls. The statistics about women prisoners in America today are similar to the incarcerated women in the above films (although the films are set in the Philippines, which allowed for low production costs). A majority are victims of abuse and rape, and have been incarcerated for nonviolent crimes.

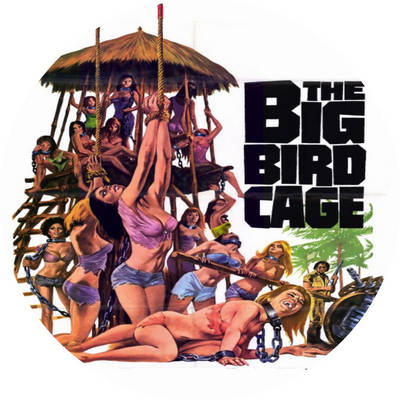

The portrayal of women in prisons–whether the reality, the fictionalized account of reality, or the exploitation genre–says a great deal about systematic patriarchy and how it hurts women. In Big Doll House, Women in Cages, and The Big Bird Cage, women can be violent rapists. They can be vengeful and seek justice. They can be victims and victors. They can be real–albeit with an unreal amount of lip gloss. The complexity of these stories is sadly hidden under the iconic shower scenes, which is incredibly unfortunate.

Ultimately, seeing films like this as simply movies about prison boobs is patriarchal. And a patriarchy similarly cages women and dismisses their roles as little more than sex object and figurative (and literal) prisoner.

But if we read these films as feminists, we can see the full spectrum of female possibility–which can sometimes be gruesome–depicted on screen alongside a critique of patriarchal systems.

Grier’s early films, though typically disregarded as exploitative in nature, are remarkable in their commentary on patriarchy.

These films provide biting commentary against patriarchy and about feminism, anti-racism, and pass the Bechdel Test with flying colors, all with incredibly diverse casts. It’s too easy to dismiss these early-70s exploitation films as just that–just like it’s too easy to dismiss women and women’s stories.

Recommended Reading: “Roger Corman’s New World Pictures,” “The Women in Cages Collection (Review)”

__________________________________________________________

Leigh Kolb is a composition, literature and journalism instructor at a community college in rural Missouri.

3 thoughts on “Before There Was ‘Orange is the New Black,’ There Was Roger Corman’s ‘Women in Cages’”

Comments are closed.