Tackling the sensitive issue of child loss isn’t easy. Some screenwriters excel at it, while others take the easy option of sending their central female character spiralling into the abyss of depression. In reality this is sometimes the case, but not all audiences are entirely comfortable witnessing a demented mother grieving in a way that’s more sensational than true to life.

Are these women ever portrayed correctly? Is there even a correct way to characterize women who have suffered miscarriage, stillbirth, or cot death (SIDS)? Are audiences brainwashed into thinking all bereaved mothers behave in a specific way?

It’s true there’s a need to educate people by showing such tragedies on screen, but are we getting it right? If so…how? If not…why?

Using British soap

Eastenders as an example, there have been various storylines involving infant deaths, be they before or after birth. The grieving mothers have been portrayed in different ways, which is a good thing as no parent who has suffered child loss will react in exactly the same way as another.

Eastenders is set in a fictitious borough in East London called Walford, and the storylines focus on the inhabitants of a specific area called Albert Square. The soap has come under fire many times for its controversial storylines which are generally described as a constant stream of doom and gloom, punctuated by repetitive and predictable sub-plots.

You’d be hard-pressed to find a more bizarre representation of real life and, fairly recently, many soap addicts were up in arms about the tragic cot death of James, a newborn baby boy, and his frantic mother Ronnie’s deranged way of dealing with it.

Their anger was fueled by the sight of Ronnie taking her dead baby to the home of another couple and swapping him for their healthy newborn son, Tommy. This led Tommy’s parents to believe it was their baby who had died instead of Ronnie’s. The storyline was set to run for many months, but it was cut short to only four months due to constant criticism.

|

| Ronnie holds her baby, James, for the last time before swapping him for Tommy |

The problem with soaps is that they can run any storyline they want without worrying too much that their audiences will cease to watch. Sadly, this meant Eastenders failed miserably to portray the tragic plight of Ronnie (Samantha Janus) as she spent four hard months being branded a complete nutter by most of the other characters…including her own husband.

When considering young audience members alone, you have to ask yourself if their already limited understanding of the world could prompt them to not only conclude from Eastenders that all bereaved mothers are lunatics, but behave similarly toward them in future.

Many adults are also unaware of the actual implications of the real life loss of an infant, and any misconceptions they already have could easily be reinforced by an exaggerated storyline such as Ronnie’s.

Sadly, many mothers will resist talking about their losses to new acquaintances just to avoid such adverse pre-judgement or an opposite reaction of forced sympathy.

Samantha Janus is a well-respected actress in the UK whose character, Ronnie, was first portrayed as a shrewd, strong, witty, no-nonsense woman. So it’s very sad that she was forced to lead Ronnie into a succession of disasters, which ultimately led to her downfall. The writers ran riot with her character, crushing her personality to a point where it was unrecoverable.

|

| Ronnie’s grasp of reality loosens as she becomes more mentally unstable |

Ironically, script submissions are often invited by TV and film producers with the emphasis on creating strong female characters. However, soap writers seem all too eager to completely and utterly smash these women down to the point of no return. It’s one thing to cleverly show different sides to their personality, but to completely destroy a useful and inspirational character is unnecessary and sadistic.

Parallel to Ronnie’s breakdown was the devastation of Kat (Jessie Wallace), the mother of Tommy, the boy who was taken from his cot by Ronnie and swapped for James. So, not only did we have one grieving mother running around with a kidnapped baby, we also had another mother who had no idea her baby was still alive. She and her husband even buried Ronnie’s baby thinking he was theirs.

Thankfully, Kat was portrayed very differently. Her character had always been feisty and aggressive, and she didn’t hold back with her frustration during the four months her baby was thought to be dead. Of the two women, Kat’s behaviour was far more believable, and her determination to get through her ordeal was refreshing to see.

|

| Kat and husband, Alfie, believe they are burying their own son, Tommy |

Jessie Wallace played her part with incredible plausibility, and Samantha Janus, regardless of her personal disapproval of the plot, did an amazing job as well. However, I’m without a single doubt that the storyline as a whole should never have been written in the first place.

As much as I appreciate that soaps want to shock and surprise us, using infant loss and the pain of a grieving mother as part of a badly-conceived storyline does nothing but trivialize the emotions and obstacles that would be faced by her in reality.

As a mother who has suffered three stillbirths and several miscarriages, I welcome storylines involving infant loss, and just because I can’t relate to the extreme behaviour that some women present doesn’t mean their story shouldn’t be told.

However, I’m very disappointed in the way a lot of writers will either reduce their character to a quivering mess or send them completely round the twist. If you’re broadcasting to millions of adults and children alike, there really has to be some kind of responsibility taken for the sort of messages being repeatedly sent out.

The creators of Eastenders defended the storyline by arguing that Ronnie would have behaved as she did given the knock-on effect of previous traumas she’d suffered. They also said they were in no way suggesting all grieving mothers would behave similarly. However, the insinuation was there for all to see. Let’s face it…since when did intentions have any bearing on what is ultimately perceived? Perception is a personal thing, unique to every individual.

I hope fewer writers will be tempted to infer that a mother’s loss invokes the need to possess another woman’s child. Knowing she will never hold her own child again is hard enough to deal with. Being portrayed as a psychopath on screen is just adding insult to injury.

Also, suggesting that grieving fathers are better able to muster the strength to support their wives or girlfriends, further implies that women are generally less mentally equipped.

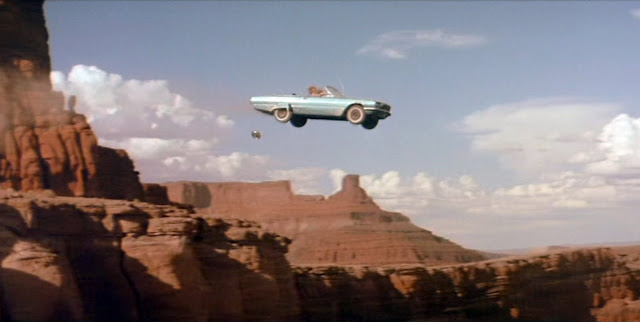

Hopelessness and depression are often paths along which a writer will take a grief-stricken mother. So imagine my joy when I came across Marc Forster’s very thought-provoking film,

Everything Put Together. Even thirteen years on, it’s still as poignant as it was when he first directed it in 2000.

In this film, Angie (Radha Mitchell) and two of her friends, Barbie and Judith, are expecting babies. At the beginning of the film, we see Angie help Judith deliver a healthy baby boy, and many of the first few scenes show Angie being embraced by what appears to be a very tight network of friends. Angie is even asked to be Godmother to Judith’s baby.

|

| Initially, Angie appears to be surrounded by a close network of friends |

Sadly, Angie’s own baby, Gabriel, is born perfectly healthy but dies as a result of SIDS while they are both still in hospital. Unbelievably, and without Angie’s permission, her friends immediately go to her house to help pack away the nursery furniture and clothing. We see them loading it all into a lorry in the black of night as if it’s something to be ashamed of and get rid of as soon as possible.

Not only do Angie and her husband lose their baby, their friends begin to desert them. Angie is even more alone because she’s not very close to her own mother and cannot even bring herself to reveal the sad news of Gabriel’s death during a phone call.

Angie is still eager to make a fuss of Judith’s baby, but Judith recoils at her advances, and when Angie visits Judith and finds her way to her baby’s bedroom, she shares a very special moment with him. However, Judith is openly alarmed and throws her out of the house.

|

| Angie shares a special private moment with Judith’s newborn son |

Similarly, when a heavily pregnant Barbie spots Angie shopping in a baby store, she’s very unresponsive, especially when one of her little boys asks about Gabriel. Angie is happy to show him a picture and talk about him, but Barbie sends her children out of the shop and apologizes to Angie for the questions.

|

| Angie is more than happy to discuss Gabriel with Barbie’s children |

Yet another example of the breakdown of Angie’s friendships is when Judith throws away Angie’s invitation to her baby’s Christening. However, the maid finds it in the bin and sends it anyway. It’s very sad to watch Angie walk alone towards the altar after the Godparents are asked to step forward only to realize she’s no longer needed.

|

| Angie has no idea she is no longer Godmother to Judith’s baby |

What I love about this film is, unlike some other stories of infant death, we’re not forced to watch a long scene after the death occurs. Straight away, Angie is trying to carry on with her life. She’s obviously torn apart by the death of her baby, but she tries to hold it together in an attempt to retain her identity as the person she was before he died.

I’m so glad the writers afforded her the strength to do this because, in reality, a recently bereaved mother will often behave in such a way that nobody around her would even know what she’s suffered. This is highlighted in the film when a mother at the local park is happy for Angie to hold her baby boy while she attends to another of her children. Angie is glad of the opportunity to feel “normal” in someone else’s eyes.

Some may find it disturbing to watch Angie ask to see her son’s body before calmly announcing to the morgue attendant, “That’s not my baby.” However, I’m completely satisfied with this; it shows us how much she wants her son to still be alive. That’s not disturbing…it’s just very sad.

|

| On seeing Gabriel at the morgue, Angie denies he is her baby |

This film also doesn’t waste time on a lengthy funeral scene with lamenting on-lookers or over-the-top wailing. What we witness is a very quiet minute’s worth of an almost silhouetted couple waiting to bury their child. No dialogue and no gratuitous crying…just a scene I myself can completely identify with.

Gradually, we see Angie and her husband appreciating that they still have each other and accepting that their so-called friends are more concerned with how Gabriel’s death might affect their own perfect lives than being the supportive friends we first thought them to be.

Finally, we see Angie surprised by a phone call from Judith, who quickly and bluntly admits she misdialled while trying to phone Barbie. This is bad enough, but then Angie feels she needs to tell Judith and Barbie she’s pregnant again before they will allow her back into their lives.

Angie lies to them both, amid congratulations during a three-way call, and we’re in no doubt she now realizes how shallow and untrustworthy they are. The closing shot of her face tells us Angie has learned a harsh lesson about friendship–one she will never forget.

|

| A three-way call with Judith and Barbie reinforces Angie’s opinion of them |

It’s not uncommon for women to feel empowered to make drastic changes after losing a child. They may, understandably, become far less tolerant of others due to the realization nobody at all can break them down any further than they’ve already been broken.

Fortunately for soap and serial drama producers, they already have the luxury of knowing millions of people will tune in to watch, no matter what is presented during each half-hourly or hourly slot. However, a filmmaker has only a short space of time to create something believable and watchable. Also, a film is not automatically guaranteed a loyal audience and relies heavily on its credibility as an individual piece.

Researching personal stories of loss is important, but I wonder how much is ignored because it would be too difficult to translate to film or television. It’s not easy to expose the darker, hidden thoughts that can really bring a broken heart to the surface–and to the screen–and writers often make the mistake of allowing their characters to disclose their heartbreak at every opportunity through unnecessary dialogue.

In reality a mother is likely to want to keep her darker or more painful thoughts to herself so she can at least feel in control of what she does and doesn’t share. Your innermost feelings are a very strong reminder of your love for your baby, so it’s comforting to hold them close and keep them safe for as long as possible.

When some writers get it wrong…it’s often due to their inability to get it totally right given the limitations. I, therefore, applaud the writers who strive to get it as right as they possibly can and trust in an actress’s ability to give her role the depth of emotion it merits and, in so doing, the credibility it will bring to her character.

———-

Angela Smith is a 45-year-old mother living in Kent, UK with her partner and four lovely children. She enjoys writing plays, short stories, TV/film reviews, and articles for satirical web sites.