|

| Bellflower (2011) |

|

| Milly and Woodrow |

|

| A turn from romance to horror. |

The radical notion that women like good movies

|

| Bellflower (2011) |

|

| Milly and Woodrow |

|

| A turn from romance to horror. |

|

| Marion Cotillard and Owen Wilson in ‘Midnight in Paris’ |

In Allen’s latest Oscar-nominated endeavor, Midnight in Paris, Gil Pender (Owen Wilson) is a successful Hollywood screenwriter struggling to write his first novel. He visits Paris with his constantly complaining fiancé Inez (Rachel McAdams), as he yearns to live amongst his literary idols in the Roaring Twenties. Gil discovers that at midnight, he is able to transport to 1920s Paris and hobnob with writers, musicians and painters. A love letter to Paris and artists, Midnight in Paris explores the dichotomy between illusions of nostalgia and pragmatically embracing the present.

Allen has a knack for evoking the visceral beauty of a city: NYC in Annie Hall and Manhattan, Barcelona in Vicky Cristina Barcelona, Paris in Midnight in Paris. With lush cinematography, Allen capturesthe seductive allure and breathtaking romance of Paris. He also infuses the film with myriad authors and artists from the 1920s, a bibliophile’s dream. These delightful distractions almost made me forget (almost) that while an okay film, it’s certainly not a great one.

Now, I didn’t hate Midnight in Paris like my kick-ass colleague Stephanie. But I totally understand why she did because it royally pissed me off too. The portrayal of women in this film is fucking problematic.

Kathy Bates is fantastic as writer and art collector Gertrude Stein. Yet she’s highly underutilized, striving to make the most of her small role. Incredibly influential, we witness Stein’s Parisian salon which attracted talented writers, like Ernest Hemingway and Ezra Pound, whom she advised and mentored. After reviewing his manuscript, Gertrude bestows Gil with her wisdom: “We all fear death and question our place in the word. The artist’s job is not to succumb to despair but to find an antidote for the emptiness of existence.” Aside from Gertrude, none of the female characters are either truly likeable, interesting or complex individuals.

Audacious Zelda Fitzgerald (Alison Pill, who tries her best to imbue her with charm), F. Scott Fitzgerald (Tom Hiddleston)’s wife and a writer in her own right, diminishes her artistic talent by saying, “…and I realize I’ll never write a great lyric and my talent really lies in drinking.”

An “art groupie” muse, Adriana (Marion Cotillard) designs couture fashion and becomes the object of Gil’s affection, despite his fiancé. When Gertrude reads the first line of Gil’s book aloud, Adriana praises it saying she’s “hooked” and later calls his musings on the “City of Light” poetic. Enamored with her, they begin to spend their evenings talking and walking around Paris. Cotillard is a divine actor. But her character is beige and boring. Although I must admit I’m glad Adriana ultimately chooses her own path.

In addition to seeking Stein’s advice on his book, Gil turns to another woman, an art museum guide (Carla Bruni), for advice on being in love with two women at the same time. Oh, and he also flirts with 25-year-old Gabrielle (Léa Seydoux) (cause you know, that’s what middle-aged dudes do) who sells old records from the Jazz Age and shares his love of Paris in the rain.

|

| Owen Wilson and Rachel McAdams in ‘Midnight in Paris’ |

Now, I don’t automatically have a problem with a villainous or unlikeable female character, especially since there are so many female roles in the film. In fact, I often lament how unlike men, women are not allowed to play unlikeable or unsympathetic characters. But I have a huge problem with the “nag” role. The cliché of women as “nags” permeates pop culture.

I also have a huge problem that the seemingly sole reason Inez was made so horribly despicable was to “allow” Gil to cheat on his fiancé. The audience would sympathize with Gil for kissing another woman, buying her trinkets, baring his soul to her and planning to sleep with her even though he was engaged because his fiancé was such a shrew. Oh that’s right, I forgot! It’s okay to cheat on someone as long as they’re an asshole.

Allen told Rachel McAdams that she should play this role as she should “want to play some bitchy parts” as they’re more interesting. Maybe. But not this part. I didn’t find her character interesting at all. Yes, McAdams tries her best with the material she’s given. But the character is one-dimensional and annoying, lacking any depth or complexity.

Midnight in Paris, like pretty much all of Allen’s films, lacks diversity. They’re a sea of white with no people of color anywhere in sight. Oh I take that back. There’s a black woman in a car that Gil gets in on his “way” to the 1920s, one shot of Josephine Baker (Sonia Rolland) dancing that lasts all of 30 seconds and a few black people watching her dance.

Along with race, sexual identities are also omitted. The film contains three famous lesbians: Gertrude Stein, Stein’s life partner Alice B. Toklas (Thérèse Bourou-Rubinsztein) and writer Djuna Barnes (Emmanuelle Uzan). Of all three, Gil only alludes to Djuna’s sexuality when he says she led when they danced together. So lesbianism is almost completely erased, paving the way for good ole’ heteronormativity.

The only overt gender commentary occurs when Ernest Hemingway (Corey Stoll) says, “Pablo Picasso thinks women are only to sleep with or to paint,” but he believes “a woman is equal to a man in courage.” Which is interesting since Allen is a person who in his personal life doesn’t always believe equality in relationships is desirable: “Sometimes equality in a relationship is great, sometimes inequality makes it work.” (???) Yeah, this explains a lot. He also has a penchant for younger women, in his movies and in reality, because younger women are more innocent, “before they get spoiled by the world.” Gag.

I swear people nominated Midnight in Paris for so many awards because Hollywood is lazy. Rather than nominating ground-breaking, intelligent films like Pariah, The Whistleblower or Young Adult, this gets nominated because Allen is a famous, old, white male director. Good job, Hollywood. Way to keep perpetuating the dude machine.

The film suffers from a major woman problem. The women in the film are just as intelligent and talented as their male contemporaries. Gil turns to women for advice and guidance. Yet Allen reduces almost all of them to love interests and arm candy, nothing more than satellites to a dude.

|

| Beginners (2010) |

|

| Mélanie Laurent as Anna |

|

| Mary Page Keller as Georgia |

|

| Christopher Plummer as Hal |

I wanted to make a film about contemporary, middle-class India, with all its vulnerabilities, foibles and the incredible extremely dramatic battle that is waged daily between the forces of tradition and the desire for an independent, individual voice.More than 350 million Indians belong to the burgeoning middle-class and lead lives not unlike the Kapur family in Fire. They might not experience exactly the same angst or choices as these particular characters, but the confusions they share are very similar–the ambiguity surrounding sexuality and its manifestation and the incredible weight of figures (especially female ones) from ancient scriptures which define Indian women as pious, dutiful, self-sacrificing, while Indian popular cinema, a.k.a. “Bollywood”, portrays women as sex objects (Mundu’s fantasy).To capture all this on celluloid was, to a large part, the reason I wanted to do Fire. Even though Fire is very particular in its time and space and setting, I wanted its emotional content to be universal.

| Radha and Sita |

The reaction of some male members of the audience was so violent that the police had to be called. “I’m going to shoot you, madam!” was one response. According to Mehta, the men who objected couldn’t articulate the word “lesbian” — “this is not in our Indian culture!” was as much as they could bring themselves to say.

It isn’t only the tangible pleasures of a lesbian relationship that created such heated reactions, though that’s certainly the most obvious reason. This beautifully shot, well-acted film is a powerful, sometimes hypnotic critique of the rigid norms of a patriarchal, post-colonial society that keeps both sexes down.

Again, here’s Mehta on Fire:

We women, especially Indian women, constantly have to go through a metaphorical test of purity in order to be validated as human beings, not unlike Sita’s trial by fire.I’ve seen most of the women in my family go through this, in one form or another. Do we, as women, have choices? And, if we make choices, what is the price we pay for them?

There is a ton of information online about Fire. Here are some selected articles for further reading:

|

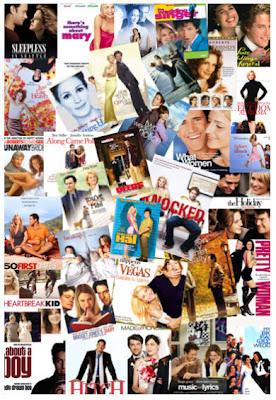

| some romantic comedies |

This guest post by Lady T previously appeared at her blog The Funny Feminist.

I also think that looking at romantic comedies is a worthwhile feminist project. I want to look at how men and women are represented in these films. I want to look at the way romantic expectations are presented in our popular culture. I want to look at issues of consent. I want to look at the way the comedy genre affects the romance genre and vice-versa.

For the parody or spoof film genre, the entry lists three examples. 0 of 3 of these examples have female protagonists.

For the anarchic comedy film genre, the entry lists two examples. 0 of 2 of these examples have female protagonists.

For the black comedy film genre, the entry lists fourteen examples. 1 of these 14 examples (Heathers) has a female protagonist without a male co-protagonist, and fewer than half have a female co-protagonist.

I think you can all start to see the pattern here, but let me continue just to belabor the point.

Action comedy films. 9 examples, 0 female protagonists.

Comedy horror films. 9 examples, 1 female protagonist (in Scary Movie).

Fantasy comedy films. 6 examples, 2 female co-protagonists (The Princess Bride, Being John Malkovich), 0 female protagonists without male co-protagonists.

Black comedy films. 3 examples, 0 female protagonists.

Sci-fi comedy films. 8 examples, 0 female protagonists.

Military comedy films. 9 examples, 1 female protagonist (Private Benjamin).

Stoner films. 4 examples, 0 female protagonists.

Some might argue with me on particular examples, but it’s obvious that dominant characters in comedy films are overwhelmingly male. (I also understand that Wikipedia is not an entirely accurate source of information, but the examples that are used to represent these different genres explains a lot about our cultural attitudes.)

If you look at the entry on romantic comedies, you see many more films that have female protagonists, or at least female co-protagonists. Especially significant is the list of top-grossing romantic comedies. 22 films are listed. More than half of them have female co-protagonists, some have one female protagonist, and one has (gasp!) more than one female protagonist (Sex and the City).

—-

|

| Best Picture nominee Slumdog Millionaire |

This is a guest post from Tatiana Christian.

|

| The Curious Case of Benjamin Button |

This is a guest post from Jesseca Cornelson.

Once I settled into the movie, however, I was able to enjoy it like the popcorn fare that it is—pleasant, but not terribly complex and with little nutritional value. My very first impression of the film was that it is one of those movies whose story is designed simply to make the viewer cry, and for me, it succeeded quite effectively in that regard. I’m a sucker for stories shaped like sadness. My second impression was to wonder why on earth I was being made to cry about the tragic love story of two imaginary white people against the back drop of Hurricane Katrina, which was a very real and epic tragedy for the city this story is set in (as well as for areas well outside New Orleans). To this second point I will return shortly.

But first, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, based on a short story of the same name by F. Scott Fitzgerald, bears a family resemblance to another film adaption of a literary source, Forrest Gump, so I wasn’t terribly surprised to find out that screenwriter Eric Roth penned both films. In each film, we follow a quirky white boy in the south from his childhood through his adventures in adolescence and early adulthood and on into maturity. Covering such a large time span, the plots are largely episodic in nature but the feeling of an overarching structure is achieved through the protagonist’s varied and lifelong relationship with a woman he’s known since childhood. Both Benjamin’s Daisy and Forrest’s Jenny are remarkable, I think, only for their beauty and their rare understanding and appreciation of their respective misfit men. Both films also present what I think of as problematically unproblematic racial relationships. I don’t necessarily believe that every film, much less those that are comedic or fantastical in nature, needs to radically explore gender and racial relationships and stereotypes, but I suppose I don’t believe that we’re sufficiently post-racial to be able to gloss over historical struggles without such glossing over itself feeling like a distraction. And I think that’s part of what renders both TCCOBB and Forrest Gump ultimately conservative films.

Before I take on what I think is Benjamin Button’s most interesting relationship—that with Queenie, the African-American woman who adopts him, I want to talk about the film’s magical realism. While TCCOBB is clearly grounded in familiar historical periods and places—1918 New Orleans, Russia pre-World War II, a Pacific marine battle (if I recall correctly), not to mention the frame story set in a 2005 New Orleans on the brink of Hurricane Katrina—the world Benjamin Button lives in is also one of magic and wonder. In the frame story, Daisy’s daughter reads to her mother from Benjamin’s diary as Daisy prepares to die. The narrative in Benjamin’s diary is further framed by the story of Mr. Gateau’s backwards running clock, built out of Mr. Gateau’s desire for his son who died in World War I to return to him. Presumably, this backwards running clock had some kind of magical influence over Benjamin, who was born the size of a baby but with the features and ailments of an old man and, as anyone who is remotely familiar with the film’s concept knows, appears to grow younger as he in fact gets older. [I have to admit that I totally thought Benjamin was going to end up as a man-sized baby at the end, an idea I got from reading too much Dlisted where Michael K would go on and on about Cate Blanchett as an old lady having sex with Brad Pitt as a old man baby. Oh, Dlisted, I can’t believe I believed you! Also, try as I might, I cannot find the posts where Michael K says this, so maybe I imagined the whole thing.]

Other than these very important magical elements, the universe of TCCOBB is relatively realistic, save for its gliding over of both the women’s movement and the Civil Rights Movement. What are we to make of this? The way I see it, since TCCOBB works hard to incorporate historic events like World Wars I & II and Hurricane Katrina, (1) the filmmakers don’t think that race and gender figure very largely in 20th century and early 21st century American history; (2) they imagine that in the same magical world where a baby can be born with the features and ailments of an old man, issues of gender and race are magically non-issues; or (3) since this is Benjamin Button’s story, he just doesn’t give a crap about race and gender. Choice three is definitely the least plausible. Benjamin Button is one very nice guy who definitely gives a crap! (Maybe the point is “Here is a really nice white guy!”) He loves his black momma Queenie (as portrayed by Taraji P. Henson)! He loves Cate Blanchett’s Daisy, even when she’s an unlovable prick. I sympathize with filmmakers and writers of all kinds, for that matter, who want to tell stories set in the historic south about something other than race. Must every story set in the historic south be about race? No, certainly, I don’t think so. But when race comes up—as it most definitely does here since Benjamin is adopted by an African-American woman—it seems strangely unrealistic to neglect the complexity of historic race relationships.

Maybe the question I should be asking is what purpose does Queenie’s blackness serve? Does her blackness make her more accepting of Benjamin when even his own father abandoned him and others were repulsed by him? Does it make the film feel integrated and inclusive while still focusing mostly on white experience? Perhaps it’s better to ask what possibilities might Queenie’s blackness have presented in this magical version of historic New Orleans. If historical gender and racial issues are going to be ignored, I think it’s an exciting possibility to think of how they might have been re-imagined altogether. That’s one of the great possibilities of speculative fiction: it allows us an opportunity to imagine how else we might be—both in utopic and dystopic senses. But even as TCCOBB neglects historical oppression, it also fails to present an imaginative alternative, and that feels like a missed opportunity.

Essentially, Queenie, as a black woman, is limited in her employment as a servant to whites. And even though she fully accepts Benjamin as her son and Benjamin does seem to love and appreciate her, he seems to fail to see how the world treats her differently and, as he grows up, he surrounds himself with white people, almost forgetting about Queenie altogether. Ultimately, the stereotype of the nurturing black woman as a loving caretaker of whites is not greatly challenged or expanded upon. African Americans are presented largely as servants. And they are truly only “supporting” characters for the white characters. Benjamin doesn’t seem to see African-American women as potential lovers or mates—only as mother figures, or rather as his mother, since the only African-American woman presented in any kind of depth is Queenie. Most strikingly, he doesn’t use his inherited wealth to get Queenie her own place or otherwise take care of her, and the last time we see Queenie, she serves Benjamin and Cate cake before retiring to bed. My heart broke for Queenie that Benjamin didn’t see to her retirement in the same way that he looked after Daisy. Is TCCOBB saying that a black woman’s motherly love is expected for free but the romantic affections of a white woman are worth money? Certainly, I think the film suggests that while black women may make good enough mothers for white boys, those boys will grow up only to desire white women. Or perhaps the film simply suggests that black women are perfectly acceptable as caretakers, but they aren’t sexually desirable like white women are. If that last sentence seems far-fetched, think about how the black women who are seen as sex symbols in our culture have or affect features often associated with whiteness. At very least, it seems that the role of lover is elevated above that of mother.

This could have been a more radical movie—and not just one in which a white character has a revelation about what it’s like to know and love black people but one whose very imaginings might show how our racial conceptions and constructions might be otherwise. Instead, we get the opposite: race relations are sanitized of all conflict, while the segregation of family and romantic relations is upheld, with the sole exception of Queenie and Benjamin.

Queenie’s preposterous explanation that Benjamin is her sister’s son “only he came out white”—possibly the film’s most hilarious moment—suggests a missed opportunity. What if in this imagined world black women commonly had white babies and vice versa? Even in our own world, racial designations aren’t as clear cut as we often assume them to be. (See “Black and White Twins”; “Parents Give Birth to Ebony and Ivory Twins”; “Black Parents . . . White Baby”; and “My Affirmative Action Fail”.) What if TCCOBB totally upended everything we think we know about race and women’s roles in the south of the past? Wouldn’t that be interesting?

Moreover, it’s one thing to neglect race and gender issues of the past, but what about in the frame story of the present? All of the nurses and caretakers in Daisy’s hospital are also black women. Daisy is kept company by her daughter, Caroline, and a black woman the same age as Caroline, who eventually leaves to check on her son and never returns to the movie. WTF? Why is she there? Is she Caroline’s girlfriend? A good friend? If we’re not going to see her again, why is she there in the first place? Okay, I looked up the script. For what it’s worth, it specifies that she’s “a young Black Woman, a ‘caregiver,’” though nurses in scrubs are also present and Dorothy dresses in civilian clothes and spends most of her screen time thumbing through a magazine. I so wish that Dorothy had been Caroline’s girlfriend or wife.

And what of Hurricane Katrina? In the end, all we see is water rising in a basement, flooding the old train station clock. There’s nothing about what happened in the hospitals, in the Ninth Ward, in the attics, in the streets, in the Superdome. I don’t even know what to say about that. That the preposterously tragic love of two imaginary white people trumps and erases all the suffering of real, mostly black people? Even through my great big ole sappy tears as Daisy dies, that just doesn’t feel right to me.

Finally, I am reminded that part of my reluctance to watch The Curious Case of Benjamin Button lies with its format as a film. Over the past decade, I’ve grown to prefer serial dramas to just about everything—film, books, whatever (though I’ve recently become consumed with popular fantasy and horror novels). HBO led the way and remains at the top of the serious television game. Deadwood and The Sopranos developed true ensemble casts with richly developed morally-complicated characters shaped by their social, historic, and economic milieux, with deft dialogue that could be emotionally moving or belly-shaking hilarious. The mere invocation of Hurricane Katrina makes it impossible for me not to compare the long but ultimately light fare of The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, which aside from its technical and artistic wizardry is ultimately forgettable, with the robust, lifelike, brilliant work of art that is Treme. Where TCCOBB uses its historical setting like a painted backdrop to affect historic depth without actually engaging history, Treme is a masterpiece of the fictionalized drama of the everyday real life of one of America’s great cities. Where women and African Americans are given roles in TCCOBB that support white stars, every character in Treme’s diverse cast is treated as the star of his or her own life, and they are richly complicated people whose lives are never defined solely by their relationship to white main characters. So that’s my loopy recommendation about The Curious Case of Benjamin Button: you’re better off watching Treme.

The Curious Case of Benjamin Button was nominated for thirteen Academy Awards in 2009. It won three Oscars for art direction, makeup, and visual effects. It was nominated for cinematography, costume design, directing, film editing, original score, sound mixing, best picture, best actor in a leading role, best actress in a supporting role, and best adapted screenplay.

This is a guest post from Megan Kearns.

|

| Juno |

It turns out, however, that after an initial adjustment period to the dialogue (and a question about whether the film is set in the early ‘90s), Juno turns out to be planted in a feminist worldview, and is a film that teenagers, especially, ought to see. It was thoroughly enjoyable, funny and touching. I liked it so much that I watched it again, but when I started to write about it, what I liked about the movie became all the more confusing. I loved the music, although Juno MacGuff is way hipper than I was (or am), and I saw a representation that reminded me of myself at that age. I saw a paternal relationship that I never had and a familial openness that I’ve also never had. I saw characters who I wanted as my childhood friends and family.

It turns out, however, that after an initial adjustment period to the dialogue (and a question about whether the film is set in the early ‘90s), Juno turns out to be planted in a feminist worldview, and is a film that teenagers, especially, ought to see. It was thoroughly enjoyable, funny and touching. I liked it so much that I watched it again, but when I started to write about it, what I liked about the movie became all the more confusing. I loved the music, although Juno MacGuff is way hipper than I was (or am), and I saw a representation that reminded me of myself at that age. I saw a paternal relationship that I never had and a familial openness that I’ve also never had. I saw characters who I wanted as my childhood friends and family.  The film’s real progressive moment comes when Juno realizes that her idea of perfection isn’t perfect. She realizes that a father who doesn’t want to be there would be as bad as a mother who hadn’t wanted to be there. She sees that a father isn’t a necessity–or perhaps simply that two parents aren’t a necessity. Yet what does this all add up to mean? There’s certainly a moment of female solidarity (and this isn’t the only one, certainly, in the film), and a difficult decision that she makes independently. But, as with other conclusions I’ve made, I’m left with the question of “So what?”

The film’s real progressive moment comes when Juno realizes that her idea of perfection isn’t perfect. She realizes that a father who doesn’t want to be there would be as bad as a mother who hadn’t wanted to be there. She sees that a father isn’t a necessity–or perhaps simply that two parents aren’t a necessity. Yet what does this all add up to mean? There’s certainly a moment of female solidarity (and this isn’t the only one, certainly, in the film), and a difficult decision that she makes independently. But, as with other conclusions I’ve made, I’m left with the question of “So what?”

I’d like to start this review with a confession: Atonement is the second book in my long history of reading that has made me so angry, so upset, that I literally threw it across the room.

Both as an Academy Award-nominated (and winning, for soundtrack) film and as a book adaptation, Joe Wright’s Atonement succeeds. The film is a gorgeous and gritty, if frustrating, portrait of childhood, of war, of love, of lies and the lies one tells to correct them.

The first section of the film and novel set up the plot. The wealthy Tallis family has temporary custody of their lesser-off red-headed cousins, the Quinceys, and young Briony (Saoirse Ronan) is determined to lead them all in a play to celebrate her older brother Leon’s homecoming. Mother Tallis is sick in bed, and older sister Cecilia (Keira Knightley) is awkward around the son of the Tallis’s lawn worker, Robbie (James McAvoy) and excited to hear that her brother is coming home, despite news that he’s bringing along a friend, cocky Paul Marshall.

In direct contrast to this innocence comes Paul Marshall, introduced as a dapper gentleman who intends to make money off of the war with his Army Amo chocolate bar factory. He descends upon the safe haven of the nursery where Lola is meant to be watching over her twin brothers. “You have to bite it,” he says, handing her a bar of chocolate, his face stony.

The sexuality, too, of Robbie has another angle. His attempts at a polite apology devolve quickly into crude sexual expression. Robbie is faced with the sheer absurdity and irrationality of expressing sexual attraction to one who is of a higher class. Paul Marshall experiences the opposite problem, his power over Lola used to his advantage as he inflicts first rough treatment and then a rape in the woods. That power keeps Lola from seeing the truth, that she has been mistreated, brutally; Paul Marshall keeps Lola at his side, and she eventually marries him.

What follows is Rob and Briony’s means of atoning for their crimes. Rob, unable to fight the accusation against the wealthy and certain young Tallis, is sentenced to prison and then to fight in WWI. Briony, realizing years later that there were cracks in what she witnessed, that there are, perhaps, alternate truths, becomes a nurse in an attempt to undo some of the wrong she has inflicted upon Cecilia and Robbie.

A story is being crafted, an attempt to fill in the blanks. An attempt to create rational cause and effect as happens in all stories when we are young. An attempt to understand what must be truly random and unpredictable. Motive must be established.

But of course, things don’t follow a logical order. The wrong person is blamed for a tragedy while another gets off scot-free. War happens and the best and worst of us are lost, caught in causes we might not respect ourselves. Illness, a car crash, a lightning strike. Do we blame Briony, then, for trying to set order in her confusing world? Do we blame her for attempting to set things right that she helped to set wrong? I remember upon first completing the novel, my rage was so complete, so strong. I hated Briony for what she had done, for creating ugly and beautiful lies to cover up the truth, for believing that life was as simple as “Yes. I saw him with my own eyes.” I hated Briony for the very reasons that I love reading and watching films: writers and directors create lies for us, and we indulge in them. Fiction is called such for a reason–it isn’t real.

The soundtrack, interlaced with the sounds of a typewriter, never lets us completely forget that this is a story that is being crafted. It is no mistake that the first shot of the movie is Briony typing away at her play, “The Trials of Arabella,” taking her work very seriously. Briony expresses the difficulty of writing: that a play depends on other people.

The difference between play and story, as Briony postulates, are similar to the difference between novel and film. McEwan spends pages describing the intricacies of the vase, complete and then broken, whereas in a film, the vase is simply there. A long camera shot transports the viewer from room to room; instead of the turn of pages, the soundtrack interacts with the actions on screen instead of, for example, a rowdy neighbor or interrupting child pulling attention from the work.

While it is, in a way, refreshing to give the narrative over so completely to a woman in what is most certainly not a “chick flick,” and while Cecilia appears to be a strong, fierce woman in charge of her own sexuality, and while Briony, if not the most trustworthy of narrators, is more than skilled enough to do the job of telling this story, both of their stories center around Robbie. Even small conversations between Briony and Cecilia, Briony and Lola, Briony and a young nurse at training devolve quickly into a discussion of Leon, or Robbie, or marriage.

Any deconstruction of the traditional romantic narrative does have the potential to be feminist, however in this case, because the story is filtered not only through Briony Tallis’s obsession with that very narrative but through a male author and director, the deconstruction is seen as a loss of something good. A loss of cherished innocence, of childlike femininity.

There is no denying the technical mastery of Atonement. Simply look at the long shot as Robbie arrives at Dunkirk, despair and small hope surrounding him and swooning around him as the camera floats through soldiers waiting. Look at small consistent hints of cracks in the narrative, look at changes in perspective looped together by setting and soundtrack. Atonement is a master work of fiction and of film, but feminism is not something I believe it can claim.